path 843 to 866 [2-9

advertisement

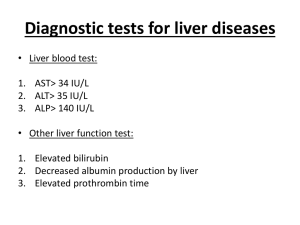

Path 843-866 Viral Hepatitis Systemic viral infections can involve liver in o Infectious mononucleosis (EBV); may cause mild hepatitis during acute phase o CMV infection, particularly in newborn or immunosuppressed patient o Yellow fever virus o Infrequently in children and immunosuppressed, liver affected in course of rubella, adenovirus, herpes virus, or enterovirus infections Hepatitis A – self-limited disease w/incubation period of 3-6 weeks; only rarely causes fulminant hepatitis o Acute HAV tends to be sporadic febrile illness o Small, non-enveloped, positive-strand RNA picornavirus that occupies own genus (Hepatovirus) Icosahedral capsid; can be cultured in vitro o Spread by ingestion of contaminated water and foods; shed in stool for 2-3 weeks before and 1 week after onset of jaundice Spread may occur by consumption of raw or steamed shellfish that concentrate virus from seawater contaminated w/human sewage o CD8+ T cells play key role in hepatocellular injury during HAV infection o Specific IgM antibody against HAV appears in blood at onset of symptoms (marker of acute infection) IgG antibody appears ina few months, and IgM response declines (lifelong immunity) – no routinely available tests for IgG anti-HAV (presence inferred from difference between total and IgM anti-HAV o HAV vaccine effective in preventing infection Hepatitis B can produce acute hepatitis w/recovery and clearance of virus, nonprogressive chronic hepatitis, progressive chronic disease ending in cirrhosis, fulminant hepatitis w/massive liver necrosis, and asymptomatic carrier state o Chronic liver disease precursor for development of hepatocellular carcinoma o Spread through close bodily contact through breaks in skin or mucous membranes; unprotected sex or IV drug use can spread o Incubation period of 4-26 weeks o HBV remains in blood until and during active episodes of acute and chronic hepatitis o In U.S., 70% of those infected have mild or no symptoms and don’t develop jaundice; rest have nonspecific constitutional symptoms (anorexia, fever, jaundice, and upper right quadrant pain) Infection self-limited and resolves w/o treatment; chronic and fulminant disease rare o Member of Hepadnaviridae family of DNA viruses; 8 HBV genotypes Mature HBV virion is spherical double-layered Dane particle that has outer surface envelope of protein, lipid, and carb enclosing electron-dense hexagonal core Partially double-stranded circular DNA molecule Genome contains 4 open reading frames coding for Nucleocapsid core protein (HBcAg (hepatitis B core antigen)) and longer polypeptide w/precore and core region (HBeAg (hepatitis B “e” antigen)) o Precore region directs HBeAg toward secretion into blood; HBcAg remains in hepatocytes for assembly of complete virions Envelope glycoproteins (HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen)), which consist of 3 related proteins (large HBsAg (containing Pre-S1, Pre-S2, and S), middle HBsAg (containing PreS2 and S), and small HBsAg (containing S only)) o Infected hepatocytes capable of synthesizing and secreting noninfective surface protein (mostly small HBsAg) Polymerase that exhibits both DNA polymerase activity and reverse transcriptase activity; genomic replication occurs via intermediate RNA template through unique replication cycle DNA RNA DNA HBx protein – necessary for virus replication and may act as transcriptional transactivator of viral genes and wide variety of host genes o Implicated in pathogenesis of liver cancer o Natural course of disease followed by serum markers HBsAg appears before onset of symptoms, peaks during overt disease, and declines to undetectable levels in 3-6 months Anti-HBs antibody rises when acute disease over; not detectable for few weeks to several months after disappearance of HBsAg; may persist for life, conferring protection HBeAg, HBV-DNA, and DNA polymerase appear in serum soon after HBsAg; signify active viral replication, infectivity, and probable progression to chronic hepatitis Appearance of anti-HBe antibodies implies acute infection peaked and is on wane IgM anti-HBc becomes detectable in serum shortly before onset of symptoms, concurrent w/onset of elevated serum aminotransferase levels (indicative of hepatocyte destruction) Over period of months, IgM antiHBc replaced by IgG anti-HBc o Occasionally, mutated strains of HBV emerge that don’t produce HBeAg but are replication competent and express HBcAg Ominous development – appearance of vaccine-induced escape mutants, which replicate in presence of vaccine-induced immunity o Very low levels of HBV DNA can be detected by PCR in blood of some individuals who may have anti-HBe antibodies; persists for many years o Virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ IFN-γ-producing cells causes resolution of acute infection o Many chronic carriers have virions in hepatocytes w/no evidence of cell injury; hepatocyte damage results from damage to virus-infected cells by CD8+ CTLs o Can be prevented by vaccination w/purified HBsAg produced in yeast; induces anti-HBs antibody response in 95% of infants, children, and adolescents Hepatitis C – most common chronic blood-borne infection; progression to chronic disease occurs in majority of HCV-infected individuals, and cirrhosis eventually occurs in 20-30% of patients w/chronic HCV infection o Most common cause of chronic liver disease in U.S.; most common indication for liver transplant o Member of Flaviviridae family; small enveloped, ss RNA virus; genome codes for single polyprotein w/one open reading frame 5’ end encodes highly conserved nucleocapsid core protein, followed by envelope proteins E1 and E2 2 hypervariable regions (HVR 1 and 2) present in E2 sequence Protein (p7) functions as ion channel Toward 3’ end are 6 less conserved nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B NS5B is viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3’ sequences of both positive and negative-strand RNAs contribute cis-acting functions essential for viral replication Secondary structure and protein-binding properties of highly conserved nontranslated regions promote HCV /RNA synthesis and genome stability through binding of various host and viral proteins Virus inherently unstable because of poor fidelity of NS5B; in any one patient, HCV circulates as population of divergent but closely related quasispecies E2 protein of envelope is target of many anti-HCV antibodies; also most variable region of entire viral genome, enabling emergent virus strains to escape neutralizing antibodies o o Elevated anti-HCV IgG occurring after active infection don’t consistently confer effective immunity Characteristic feature of HCV infection is repeated bouts of hepatic damage (result of reactivation of preexisting infection or emergence of endogenous, newly mutated strain) o Incubation period ranges from 2-26 weeks; in 85% of individuals, clinical course of acute infection asymptomatic and easily missed RNA detectable in blood for 1-3 weeks, coincident w/elevations in serum transaminases Anti-HCV antibodies in 5070% of acute HCV infections; in remainder, anti-HCV antibodies emerge after 3-6 weeks CD4+ and CD8+ T cells associated w/self-limited HCV infections o Persistent infection and chronic hepatitis hallmarks of HCV infection (80-85% of cases) Cirrhosis may develop over 5-20 years after acute infection in 20-30% w/persistent infection o HCV can actively inhibit IFN-mediated cellular antiviral response at multiple steps (TLR signaling in response to viral RNA recognition and signaling downstream of IFN receptors that confers antiviral state on cells) o Circulating HCV RNA persists in many patients despite presence of neutralizing antibodies; RNA testing must be performed to assess viral replication and confirm diagnosis of HCV o Characteristic chronic HCV feature is episodic elevations in serum aminotransferases w/intervening normal or near-normal periods o Fulminant hepatic failure rarely occurs Hepatitis D – RNA virus dependent for life cycle on HBV o Infection occurs with Acute coinfection – exposure to serum w/both HDV and HBV; HBV must become established first to provide HBsAg necessary for development of complete HDV virions Usually transient and self-limited; elimination of HBV leads to elimination of HDV High incidence of liver failure among addicts Superinfection – when chronic carrier of HBV exposed to new inoculum of HDV; results in disease 30-50 days later (as severe acute hepatitis) Chronic HDV infection occurs in 80-90% of patients May have acute phase (active HDV replication and suppression of HBV w/high ALT levels) and chronic phase (HDV replication decreases, HBV replication increases, ALT levels fluctuate, and disease progresses to cirrhosis or hepatocellular cancer (HCC)) Helper-independent latent infection – liver transplant; HDV detected in nuclei of grafted liver w/in few hours after transplantation w/o evidence of productive HDV infection or HBV reinfection; due to infection of allograft by HDV alone (infection by HBV prevented by Ig administered to prevent HBV reinfection) HD viremia and hepatitis ensues only when HBV escapes neutralization and coinfection of graft w/high levels of HBV replication, leading to activation of HDV by helper virus o Double-shelled particle that resembles Dane particle of HBV External coat antigen (HBsAg) surrounds internal polypeptide assembly, designated delta antigen (HDAg); only protein produced by virus Associated w/HDAg is smaller circular molecule of ss RNA Replication of virus through RNA-directed RNA synthesis by host RNA polymerase (Pol II) o IgM anti-HDV is most reliable indicator of recent HDV exposure; appearance late and short-lived Acute co-infection of HDV and HBV best indicated by detection of IgM against both HDAg and HBcAg Chronic delta hepatitis from HDV superinfection – HbsAg present in serum, and anti-HDV antibodies (IgG and IgM) persist for months or longer o Treatment limited to IFN-α o Vaccination for HBV can prevent HDV infection as well Hepatitis E – enterically transmitted, water-borne infection that occurs primarily in young to middle-aged adults o Zoonotic disease w/animal reservoirs (monkeys, cats, pigs, and dogs) o Accounts for more than 30-60% of cases of sporadic acute hepatitis in India o High mortality rate among pregnant women (20%) o In most cases, self-limiting; not associated w/chronic liver disease or persistent viremia o Average incubation period 6 weeks o Unenveloped, positive-stranded RNA virus in Hepevirus genus o Specific antigen (HEV Ag) identified in cytoplasm of hepatocytes during active infection o Virions shed in stool during acute illness o Before onset of clinical illness, HEV RNA and HEV virions detected by PCR in stool and serum o Onset of rising serum aminotransferases, clinical illness, and elevated IgM anti-HEV titers virtually simultaneous; symptoms resolve in 2-4 weeks; IgM replaced w/persistent IgG anti-HEV titer Hepatitis G – flavivirus; called HGV or GBV-C; transmitted by contaminated blood or blood products and sexual contact; not hepatotropic and doesn’t cause elevations in serum aminotransferases o Replicates in bone marrow and spleen o Doesn’t cause known human disease o Commonly co-infects individuals infected w/HIV; dual infection somewhat protective against HIV disease Clinicopathologic Syndromes of Viral Hepatitis o Acute asymptomatic infection w/recovery – HAV and HBV infection in childhood; identified incidentally on basis of minimally elevated serum transaminases o Acute symptomatic infection w/recovery – peak infectivity during last asymptomatic days of incubation period and early days of acute symptoms Disease phases: (1) incubation, (2) symptomatic preicteric phase, (3) symptomatic icteric phase, (4) convalescence o Chronic hepatitis – symptomatic, biochemical, or serologic evidence of continuing or relapsing hepatic disease for more than 6 months Most HCV infections, small number of HBV infections In some, only signs are persistent elevation of serum transaminases Physical findings include spider angiomas, palmar erythema, mild hepatomegaly, hepatic tenderness, and mild splenomegaly Lab studies show prolongation of PTT; sometimes hyperglogulinemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and mild elevations of ALK In HBV and HCV, immune complex disease may develop secondary to presence of circulating antibody-antigen complexes (vasculitis and glomerulonephritis) Cryoglobulinemia found in 35% of chronic HCV patients Age at time of infection = best determinant of chronicity for HBV; the younger they are, the more chance they will be chronic Although uncommon, patients can recover completely Goal of Tx: slow disease progression, reduce liver damage, and prevent cirrhosis/cancer HCV – any individual w/detectable HCV RNA in serum needs medical attention Tx based on combo of pegylated IFN-α and ribavirin Response to therapy depends on viral genotype (genotype 2 or 3 infections have best responses) o Carrier state – can mean (1) individuals who carry virus but have no liver disease or (2) those who harbor virus and have nonprogressive liver damage but are essentially free of symptoms or disability HBV – healthy carrier is individual w/o HBeAg but w/presence of anti-HBe, normal aminotransferases, low or undetectable serum HBV DNA, and liver biopsy shoing lack of significant inflammation and necrosis Less than 1% of infections acquired by adults produce this state Infection early in life in endemic areas gives rise to this state in 90% of cases HCV – yields carrier state in 10-40% of cases o Coinfection w/HIV – 10% of HIV patinets infected w/HBV and 30% w/HCV Chronic HBV and HCV among leading causes of morbidity and mortality for HIV patients Anti-HIV agents may cause hepatotoxicity in some patients w/HBV or HCV coinfection Morphology o HBV-infected hepatocytes show cytoplasm packed w/spheres and tubules of HBsAg, producing finely granular cytoplasm (ground-glass appearance) o HCV-infected liver shows lymphoid aggregates w/in portal tracts and focal lobular regions of hepatocyte macrovesicular steatosis o Acute hepatitis – hepatocyte injury = diffuse swelling (ballooning degeneration); cytoplasm looks empty and contains scattered eosinophilic remnants of organelles Cholestasis (bile plugs in canaliculi and brown pigmentation of hepatocytes) Canalicular bile plugs from cessation of contractile activity of hepatocyte pericanalicular actin microfilament web Patterns of hepatocyte cell death Rupture of PM leading to focal loss of hepatocytes; sinusoidal collagen reticulin framework collapses where cells disappear; scavenger macrophage aggregates mark sites of hepatocyte loss Apoptosis – caused by anti-viral CTLs; apoptotic hepatocytes shrink, become intensely eosinophilic, and have fragmented nuclei o CTLs may still be present in immediate vicinity o Apoptotic cells rapidly phagocytosed by macrophages Confluent necrosis of hepatocytes (bridging necrosis) in severe cases of acute hepatitis; connects portal-to-portal, central-to-central, or portal-to-central regions of adjacent lobules; hepatocyte swelling and regeneration compress sinusoids o Radial array of hepatocyte plates around terminal hepatic vein lost Kupffer cells hypertrophy and hyperplasia; laden w/lipofuscin pigment as result of phagocytosis of hepatocellular debris Portal tracts infiltrated w/mixture of inflammatory cells, which may spill into adjacent parenchyma, causing apoptosis of periportal hepatocytes (interface hepatitis) Cells in canals of Hering proliferate, forming ductular structures at parenchymal interface (ductular reaction) o Chronic hepatitis In mildest forms, inflammation limited to portal tracts and consists of lymphocytes, macrophages, occasional plasma cells, and rare neutrophils or eosinophils Liver architecture usually well preserved; smoldering hepatocyte apoptosis throughout lobule may occur Chronic HCV – lymphoid aggregates and bile duct reactive changes in portal tracts; focal mild to moderate macrovesicular steatosis (more prevalent in genotype 3) Continued interface hepatitis and bridging necrosis between portal tracts and portal tracts-totermianl hepatic veins harbingers of progressive liver damage Hallmark of chronic liver damage = deposition of fibrous tissue (portal tracts periportal septal fibrosis linking of fibrous septa (bridging fibrosis) esp. between portal tracts) Continued loss of hepatocytes and fibrosis results in cirrhosis; irregularly sized nodules separated by mostly broad scars (post-necrotic cirrhosis) Fulminant hepatic failure – hepatic insufficiency that progresses from onset of symptoms to hepatic encephalopathy within 2-3 weeks in those w/o chronic liver disease o In HBV-induced fulminant hepatitis, massive apoptosis o Morphology: distribution of liver destruction can be entire or random area; with massive loss of mass, liver may shrink, become limp, red organ covered by wrinkled, too-large capsule Necrotic areas have muddy red, mushy appearance w/hemorrhage Complete destruction of hepatocytes in contiguous lobules leaves collapsed reticulin framework and preserved portal tracts o Ductular reaction – proliferation and differentiation of stem/progenitor cell population in canals of Hering (oval cells); maturation of oval cells creates hepatocytes and bile duct cells If parenchymal framework preserved, regeneration resulting from hepatocyte replication can completely restore liver architecture More massive destruction of confluent lobules regeneration disorderly (nodular masses of liver cells that produce more irregular liver on healing) o Fibrous scarring may occur in patients w/protracted course of submassive or patchy necrosis cirrhosis o Liver transplant is only option for those whose disease doesn’t resolve before secondary infection and other organ failure develop Bacterial, Parasitic, and Helminthic Infections Extrahepatic bacterial infections (particularly sepsis) can induce mild hepatic inflammation and varying degrees of hepatocellular cholestasis (effects of pro0inflammatory cytokines released by Kupffer cells and endothelial cells in response to circulating endotoxin) Bacteria that infect liver directly – Staph aureus (toxic shock syndrome), Salmonella typi (typhoid fever), and T. pallidum (secondary or tertiary syphilis) Bacteria (gut flora) proliferate in biliary tree when outflow obstructed (ascending cholangitis) Malaria schistosomiasis, strongyloidiasis, cryptosporidiosis, leishmaniasis, echinococcosis, and infections by liver flukes Fasciola hepatica and Clonorchis sinensis Liver abscesses – usually caused by echinococcal and amebic infections (can be other protozoa or helminths) o Most pyogenic o Organisms reach liver by portal vein, arterial supply, ascending infection in biliary tract (ascending cholangitis), direct invasion of liver from nearby source, or penetrating injury o Morphology – bacteremic spread through arterial or portal system produces multiple small abscesses; direct extension and trauma usually cause large solitary abscesses Biliary abscesses usually multiple; may contain purulent material from bile ducts Rupture of subcapsular liver abscesses can lead to peritonitis or localized peritoneal abscesses Echinococcal infection has characteristic cystic structure – wall laminated; hooklets and intact organisms can be identified; calcification in cystic wall common o Associated w/fevere, RUQ pain, and tender hepatomegaly; jaundice may result from extrahepatic biliary obstruction Autoimmune Hepatitis Chronic progressive hepatitis; pathogenesis attributed to T cell-mediated autoimmunity (hepatocyte injury caused by IFN-γ produced by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and CD8+ T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity) o Injurious immune reaction triggered by viral infections, certain drugs (minocycline, atorvastatin, simvastatin, methyldopa, interferons, nitrofurantoin, and pemoline), and herbal products (black cohosh) Occurs w/other autoimmune disorders (SLE, celiac disease, RA, thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, ulcerative colitis) Absence of serologic markers of viral infection, elevated serum IgG and γ-globulin levels, and high serum titers of autoantibodies Type 1 – presence of antinuclear (ANA), anti-smooth muscle (SMA), anti-actin (AAA), and anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antigen (anti-SLA/LP) antibodies o Much more common than type 2 in U.S.; associated w/HLA-DR3 serotype Type 2 – anti-liver kidney microsome-1 (ALKM-1; directed against CYP2D6) and anti-liver cytosol-1 (ACL-1) Prominent inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells; clusters of plasma cells in interface of portal tracts and hepatic lobules Atypical presentation – symptoms primarily from involvement of other organ systems OR asymptomatic and progress to cirrhosis w/o clinical diagnosis Acute appearance of clinical illness common; fulminant presentation w/onset of hepatic encephalopathy w/in 8 weeks of disease osnet possible Autoimmune cholangitis – histologic destruction of bile ducts Prednisone alone or in combo w/azathioprine mainstay therapy Liver transplantation indicated for patients w/end-stage liver disease Drug and Toxin-Induced Liver Disease Most common cause of fulminant hepatitis in U.S. Genetic variability influences susceptibility to drug-induced injury, which may result from o Direct toxicity to hepatocytes or biliary epithelial cells, causing necrosis, apoptosis, or disruption of cellular function o Hepatic conversion of xenobiotic to active toxin o Immune mechanisms, usually by drug or metabolite acting as hapten to convert cellular protein into immunogen Drug reactions may be predicatble (intrinsic) or unpredictable (idiosyncratic) o Idiosyncratic drug reaction considered in any patient receiving therapeutic drug who develops evidence of liver damage Chlorpromazine – causes cholestasis in patients slow to metabolize to innocuous byproduct Halothane – can cause fatal immune-mediated hepatitis in some patients exposed to it on multiple occasions May take form of hepatocyte necrosis, cholestasis, or insidious onset of liver dysfunction Hepatic injury predictable w/overdoses of acetaminophen, Amanita phalloides toxin, CCl4, and (sort of) EtOH Acetaminophen is leading cause of drug-induced acute liver failure Idiosyncratic reactions evolve w/subacute course; usually high bilirubin levels Reye syndrome – syndrome of mitochondrial dysfunction in liver, brain, and elsewhere; characterized by microvesicular steatosis; development associated w/administration of aspirin for relief of fever Long-term methotrexate administration for psoriasis can cause liver injury (steatosis and fibrosis) Alcoholic Liver Disease – leading cause of liver disease in most Western countries o 3 forms of liver disease Hepatic steatosis – microvesicular lipid droplets accumulate in hepatocytes; w/chronic intake, lipid accumulates creating large clear macrovesicular globules that compress and displace hepatocyte nucleus to periphery of cell Fibrous tissue develops around terminal hepatic veins and extends into sinusoids Fatty change completely reversible if abstention from further EtOH intake Alcoholic hepatitis – characterized by Hepatocyte swelling and necrosis: cells undergo swelling (ballooning) and necrosis o Swelling results from accumulation of fat and water; also proteins normally exported; in some cases, cholestasis in surviving hepatocytes and mild deposition of hemosiderin in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells Mallory bodies: visible as eosinophilic cytoplasmic clumps in hepatocytes o Hepatocytes accumulate tangled skeins of cytokeratin intermediate filaments Neutrophilic reaction: neutrophils permeate hepatic lobule and accumulate around degenerating hepatocytes, particularly those w/Mallory bodies Fibrosis: activation of sinusoidal stellate cells and portal tract fibroblasts (fibrosis) o Most sinusoidal and perivenular, separating parenchymal cells o Periportal fibrosis may predominate w/repeated bouts of heavy EtOH intake Cirrhosis – irreversible; usually evolves slowly and insidiously Liver is yellow-tan, fatty, and enlarged at first; transforms into brown, shrunken, nonfatty organ Initially developing fibrous septa delicate; extend through sinusoids from central-toportal and portal-to-portal regions Regenerative activity of entrapped parenchymal hepatocytes generates uniform micronodules; nodularity becomes more prominent Scattered large nodules create hobnail appearance on surface of liver As fibrous septa dissect and surround nodules, liver becomes more fibrotic, loses fat, and shrinks Ischemic necrosis and fibrous obliteration of nodules eventually create broad expanses of tough, pale scar tissue (Laennec cirrhosis) Bile stasis develops o Short-term ingestion of 80 g EtOH [6 beers (8 oz ea) or 8 oz of 80-proof] over several days generally produces mild, reversible hepatic steatosis Daily intake of 80 g or more generates significant risk for severe hepatic injury Daily ingestion of 160 g or more for 10-20 years associated w/severe injury o Only 10-15% of alcoholics develop cirrhosis Women more susceptible to hepatic injury than men – due to estrogen increasing gut permeability to endotoxins, which increase expression of LPS receptor CD14 in Kupffer cells, predisposing to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines Cirrhosis rates higher in African Americans (with comparable intake to other races) Genetic factors – polymorphisms in detoxifying enzymes and some cytokine promoters ALDH*2 (genetic variant of ALDH) found in 50% of Asians has very low activity; unable to oxidize acetaldehyde and don’t tolerate alcohol Co-morbid conditions – iron overload and infections w/HCV and HBV increase severity o Exposure to EtOH causes steatosis, dysfunction of mitochondrial and cellular membranes, hypoxia, and oxidative stress o Steatosis results from Shunting of normal substrates away from catabolism and toward lipid biosynthesis as result of generation of excess NADH by alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase Impaired assembly and secretion of lipoproteins Increased peripheral catabolism of fat o Acetaldehyde (major intermediate metabolite of EtOH) induces lipid peroxidation and acetaldehydeprotein adduct formation, disrupting cytoskeletal and membrane function o Cytochrome P450 metabolism produces ROS o EtOH-induced impaired hepatic metabolism of methionine leads to decreased intrahepatic glutathione levels, sensitizing liver to oxidative injury Induction of CYP2E1 and other P450 enzymes by EtOH increases EtOH catabolism in ER and enhances convertsion of other drugs (e.g., acetaminophen) to toxic metabolites o Major source of calories that displaces other nutrients, leading to malnutrition and deficiencies of vitamins (such as thiamine); compounded by impaired digestive function, primarily related to chronic gastric and intestinal mucosal damage, and pancreatitis o EtOH causes release of bacterial endotoxin from gut into portal circulation, inducing inflammatory responses in liver (activation of NF-κB, and release of TNF, IL-6, TGF-α) o EtOH stimulates release of endothelins from sinusoidal endothelial cells, causing vasoconstriction and contraction of activated stellate cells (myofibroblasts), leading to decrease in sinusoidal perfusion o Cells respond in increasingly pathologic manner to stimulus that originally was only marginally harmful o Steatosis may become evident as hepatomegaly w/mild elevation of serum bilirubin and ALK o Alcoholic hepatitis appears acutely after bout of heavy drinking; often have high bilirubin, ALK, and often neutrophilic leukocytosis May clear slowly w/proper nutrition and total cessation of EtOH consumption o Lab findings of alcoholic cirrhosis – elevated serum aminotransferase, bilirubin, ALK, low protein (globulins, albumin, and clotting factors), and anemia; AST/ALT 2.0-2.5 o End-stage alcoholic liver disease causes of death: hepatic coma, massive GI hemorrhage, intercurrent infection, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatocellular carcinoma Metabolic Liver Disease Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) – group of conditions that have hepatic steatosis in individuals who consume 20 g of EtOH per week or less; most common cause of chronic liver disease in U.S. o Includes hepatic steatosis, steatosis accompanied by minor non-specific inflammation, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) o NASH – condition w/hepatocyte injury that may progress to cirrhosis in 10-20% of cases Main components = hepatocyte ballooning, lobular inflammation, and steatosis o Fibrosis occurs w/progressive disease o Condition strongly associated w/obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance o o o More than 70% of obese people have some form of NAFLD Contributes to progression of other liver diseases (HCV, HCC) Pathogenesis occurs by hepatic fat accumulation and hepatic oxidative stress Oxidative stress acts on accumulated hepatic lipids, resulting in lipid peroxidation and release of lipid peroxides, which can produce reactive oxygen species o Liver biopsy is most reliable diagnostic tool for NASH o Serum AST and ALT elevated in 90% of patients; AST/ALT ratio <1 o Droplets of fat predominantly triglycerides o Steatohepatitis (NASH) characterized by steatosis, parenchymal inflammation (mainly neutrophils), Mallory bodies, hepatocyte death (ballooning degeneration and apoptosis), and sinusoidal fibrosis o Cirrhosis may result from years of subclinical progression of necroinflammatory and fibrotic processes When cirrhosis established, steatosis tends to be reduced Hemochromatosis – excessive accumulation of body iron, usually due to abnormal regulation of intestinal absorption of dietary iron; most deposited in liver and pancreas o Iron can accumulate in heart, joints, or endocrine organs o Recessive inherited disorder caused by excessive iron absorption o Hemosiderosis – secondary hemochromatosis; caused by parenteral administration of iron or other o 98% of iron pool stored in hepatocytes o Characteristic features of disease Micronodular cirrhosis (all), diabetes mellitus (75-80%), and skin pigmentation (75-80%) Iron accumulation lifelong; injury slow and progressive Males predominate w/slightly earlier clinical presentation o Excessive iron directly toxic to host tissues Lipid peroxidation via iron-catalyzed free radical reactions Stimulation of collagen formation by activation of hepatic stellate cells Interaction of ROS and iron itself w/DNA, leading to lethal cell injury or predisposition to HCC o Actions of iron reversible in cells that aren’t fatally injured; removal of excess iron w/therapy o Main regulator of iron absorption is protein hepcidin (LEAP1) encoded by HAMP gene Also has antibacterial activity; produced in hepatocytes Transcription increased by inflammatory cytokines and iron; decreased by iron deficiency, hypoxia, and ineffective erythropoiesis Binds to iron efflux channel (ferriportin; FPN), causing internalization and proteolysis of FPN Prevents release of iron from intestinal cells and macrophages Hepcidin ultimately lowers plasma iron levels o Other proteins involved in iron metabolism Hemojuvelin (HJV) – expressed in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle Transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2) – expressed in hepatocytes, where it mediates uptake of transferrin-bound iron HFE – product of hemochromatosis gene (encodes HLA class I-like molecule that regulates intestinal absorption of dietary iron); mutation here most common adult form; most common HFE mutation is C282Y (other common one is H63D) o Mutations in HAMP or HJV cause severe form of hereditary hemochromatosis (juvenile hemochromatosis) o Mutations in HFE and TfR2 cause classic form of hereditary adult hemochromatosis o Mutations of FPN cause distinctive iron storage disease different from hemochromatosis o TMPRSS6 – serum protease that is iron sensor that suppresses HAMP expression o Morphologic changes characterized principally by deposition of hemosiderin (liver, pancreas, myocardium, pituitary gland, adrenal gland, thyroid, parathyroid, skin; detected by Prussian blue stain), cirrhosis, and pancreatic fibrosis With increasing iron load, progressive involvement of rest of lobule, along w/bile duct epithelium and Kupffer cell pigmentation Iron is direct hepatotoxin; inflammation absent Liver slightly larger, dense, and chocolate brown Fibrous septa develop slowly, leading to micronodular pattern of cirrhosis in intensely pigmented liver o Biochemical determination of hepatic tissue Fe standard for quantitating hepatic Fe content o Pancreas become intensely pigmented, has diffuse interstitial fibrosis, and may exhibit some parenchymal atrophy Hemosiderin found in acinar and islet cells; sometimes in interstitial fibrous stroma o Heart often enlarged w/hemosiderin granules in myocardial fibers (brown coloration) o Skin pigmentation – hemosiderin deposition in dermal macrophages and fibroblasts; most results from increased epidermal melanin production; gives skin slate-gray color o Joint synovial linings – acute synovitis may develop due to hemosiderin deposition; excessive deposition of calcium pyrophosphate damages articular cartilage, producing pseudo-gout o Testes may be small and atrophic; not usually significantly pigmented Atrophy secondary to derangement in hypothalamic-pituitary axis resulting in reduced gonadotropin and testosterone levels o Principal manifestations include hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, skin pigmentation (particularly sunexposed areas), deranged glucose homeostasis or frank DM due to destruction of pancreatic islets, cardiac dysfunction (arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy), and atypical arthritis In some, hypogonadism (amenorrhea in female; impotence and loss of libido in male) o Classic triad of pigment cirrhosis = hepatomegaly, skin pigmentation, and diabetes mellitus develops later in course of disease o Significant cause of death = HCC; treatment for iron overload doesn’t reduce risk o Screening involves demonstration of high serum iron and ferritin, exclusion of secondary causes of iron overload, and liver biopsy if indicated o Heterozygotes accumulate excessive iron, but not to level of significant tissue damage o High iron levels treated by regular phlebotomy; normal life expectancy o Neonatal hemochromatosis (congenital hemochromatosis) – severe liver disease and extrahepatic hemosiderin deposition; not inherited Liver injury, leading to hemosiderin accumulation, occurs in utero Extrahepatic hemosiderin deposition detected by buccal biopsy; needs to be documented for correct diagnosis No specific treatment except supportive care and liver transplant if necessary Most common causes of hemosiderosis – disorders associated w/ineffective erythropoiesis (severe forms of thalassemia and myelodysplastic syndromes) o Excess iron results from increased absorption as well as transfusions o Alcoholic cirrhosis often associated w/modest increase in stainable iron in liver cells; represents EtOHinduced redistribution of iron (total body iron not significantly increased) o Can result from ingesting large quantities of alcoholic beverages fermented in iron utensils (Bantu siderosis) o Chronic HBV and HCV infection may increase iron storage in hepatocytes Wilson disease – autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutation of ATP7B gene, resulting in impaired copper excretion into bile and failure to incorporate copper into ceruloplasmin o Marked by accumulation of toxic levels of copper, principally liver, brain, and eye o Normally 40-60% of ingested copper absorbed in duodenum and proximal small intestine; transported to portal circulation complexed w/albumin and histidine; free copper dissociates and is taken up by hepatocytes o Copper incorporated into enzymes and binds to α2-globulin (apoceruloplasmin) to form ceruloplasmin, which is secreted into blood; excess copper transported into bile; ceruloplasmin eventually desialylated, endocytosed by liver, and degraded in lysosomes; released copper excreted in bile o ATP7B gene encodes transmembrane copper-transporting ATPase expressed on hepatocyte canalicular membrane; most of patients are compound heterozygotes containing different mutations on each allele Deficiency in ATP7B protein causes decrease in copper transport into bile, impairs its incorporation into ceruloplasmin, and inhibits ceruloplasmin secretion into blood Causes copper accumulation in liver and decrease in circulating ceruloplasmin Copper causes toxic liver injury through production of ROS by Fenton reaction Once hepatic capacity for incorporating copper into ceruloplasmic exceeded, there may be sudden onset of critical systemic illness Non-ceruloplasmin-bound copper spills over from liver into circulation, causing hemolysis and pathologic changes in brain, corneas, kidneys, bones, joints, and parathyroids Urinary excretion of copper markedly increases o Liver bears brunt of injury, but disease may present as neurologic disorder Steatosis mild to moderate w/vacuolated nuclei (glycogen or water) and occasionally focal hepatocyte necrosis Acute or chronic hepatitis; moderate to severe inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis w/features of macrovesicular steatosis, vacuolated hepatocellular nuclei, and Mallory bodies Cirrhosis develops Massive liver necrosis – rare manifestation indistinguishable from that caused by virus or drugs Demonstration of hepatic copper content of more than 250 µg/g dry weight most helpful for Dx In brain, toxic injury primarily affects basal ganglia (putamen), which shows atrophy and cavitation Nearly all patients w/neurologic involvement develop eye lesions (Kayser-Fleischer rings) green to brown deposits in Desçemet’s membrane in limbus of cornea o Most common presentation acute or chronic liver disease o Neuropsychiatric manifestations – mild behavioral changes, frank psychosis, or Parkinson disease-like syndrome (such as tremor) o Biochemical diagnosis based on decrease in serum ceruloplasmin, increase in hepatic copper content (most sensitive and accurate), and increased urinary excretion of copper (most specific) o Long-term copper chelation therapy (D-penicillamine (Trientine)) or zinc-based therapy alters progress o Those w/hepatitis or unmanageable cirrhosis require liver transplant for survival α1-antitrypsin deficiency – autosomal recessive disorder marked by very low levels of α1-antitrypsin; major function of α1-antitrypsin is inhibition of proteases (neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase 3) normally released from neutrophils at sites of inflammation o Deficiency leads to development of pulmonary emphysema because activity of destructive proteases not inhibited; causes liver disease as consequence of accumulation of protein in hepatocytes o Cutaneous panniculitis, arterial aneurysm, bronchiectasis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis can occur o α1-antitrypsin synthesized predominantly by hepatocytes; member of serine protease inhibitor (serpin) family; most common genotype is PiMM Some deficiency variants (PiS) result in moderate reduction of serum α1-antitrypsin w/o Sx Rare varients (Pi-null) have no detectable serum α1-antitrypsin Most common clinically significant mutation is PiZ Expression of alleles autosomal codominant (PiMZ heterozygotes have intermediate levels) o Deficiency variants show defect in migration of secretory protein from ER to Golgi apparatus (PiZ); mutant polypeptide (α1AT-Z) abnormally folded and polymerizes, creating ER stress, leading to apoptosis Accumulated α1AT-Z in ER triggers autophagocytic response, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of NF-κB, causing hepatocyte damage o Characterized by presence of round-to-oval cytoplasmic globular inclusions in hepatocytes; acidophilic and indistinctly demarcated from surrounding cytoplasm; PAS-positive and diastase-resistant (only distinctive feature; otherwise fibrosis and hepatitis vary too much) Blobules diminished in size and number in PiMZ and PiSZ genotypes Most of globules in hepatocytes surrounding portal tracts o Neonatal hepatitis w/cholestatic jaundice appears in 10-20% of newborns w/deficiency o In adolescence, presenting Sx related to hepatitis or cirrhosis Attacks of hepatitis may subside w/apparent complete recovery or may become chronic and lead progressively to cirrhosis o Disease may remain silent until cirrhosis appears in middle to later life o HCC develops in 2-3% of PiZZ adults, usually but not always in setting of cirrhosis o o In patients w/pulmonary disease, single most important Tx is quit smoking (markedly accelerates emphysema and destructive lung disease associated w/ α1-antitrypsin deficiency Neonatal cholestasis – prolonged conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; caused by cholangiopathies (primarily biliary atresia) and disorders causing conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in neonate (neonatal hepatitis) o Finding neonatal cholestasis should prompt search for recognizable toxic, metabolic, and infectious liver diseases; once identifiable causes have been excluded, idiopathic neonatal hepatitis becomes Dx o Affected infants have jaundice, dark urine, light or acholic stools, and hepatomegaly o Morphologic features include lobular disarray w/focal liver cell apoptosis and necrosis, panlobular giantcell transformation of hepatocytes, prominent hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis, mild mononuclear infiltration of portal areas, reactive changes in Kupffer cells, and extramedullary hematopoiesis; can blend into ductal pattern of injury, w/bile ductular proliferation and fibrosis of portal tracts