In using `military` - Flinders University

advertisement

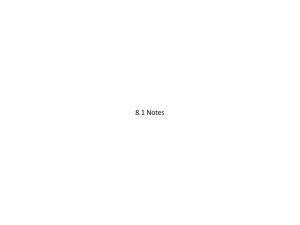

YOU ARE IN THE ARMY NOW! LYNDALL URWICK AND THE USE OF MILITARY METAPHORS PHILIP A. RITSON School of History and Politics University of Adelaide ADELAIDE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5000 Emial: philip.ritson@adelaide.edu.au LEE D. PARKER School of Commerce University of South Australia ADELAIDE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5000 Emial: lee.parker@unisa.edu.au YOU ARE IN THE ARMY NOW! LYNDALL URWICK AND THE USE OF MILITARY METAPHORS This paper examines the employment of the military metaphor by the management thinker and writer Lyndall Urwick. Urwick developed and articulated his ideas over a 60 year period in the twentieth century, arguably the longest continuous period of any management writer of his day. The study reveals the wartime context surrounding the emergence of his ideas motivated Urwick’s faith in the military approach to management. In this case of a management idea’s failure to gain traction, the importance of the congruence between management theory and societal beliefs emerges as crucial to the likely uptake of new management thinking. Lyndall Urwick (1891-1983) stands as one of the most prolific and enduring writers on management theory and practice in the twentieth century. He sustained a prolific output of books and articles over a 60 year period.1 His work is particularly noted for its persistent proselytising of Taylor’s scientific management and for its employment of military metaphors to convey his management theories and prescriptions. Urwick is unique amongst the management writers of his day in his commitment to the military perspective. This paper explores Urwick’s employment of military metaphors as a unique case of management theorising, one that failed to gain traction amongst writers and researchers of his and subsequent periods. In doing so, it offers an alternative approach to the historical study of the development of thought in management, one which focuses on the most recognisably ‘successful’ cases in the development and transmission of ideas. To this end, the paper explores not only Urwick’s articulation of the military metaphor, but also the socio-economic context that influenced his articulation of it and its reception by his audience, as well as his own rationales for his sustained advocacy of those metaphors. In presenting this historical analysis and reflection, this study offers insights into one example of the historical genesis of longstanding concepts in management thought, such as line–staff relationships and span of control. Their original intentions and orientations can be unpacked through an analysis of their originators and their contexts. In so doing, possibilities for better understanding their degree of durability and contemporary positioning can be revealed. This paper begins with a brief summary of Urwick’s own military and business background and his Taylorist persuasion and then provides illustrations of some of his most prominent military metaphors. The British industrial and professional environment as a conditioner of Urwick’s military focus, as well as his own diagnosis and rationale for that The authors would like to thank Langdon Blight (CPA Australia) and Meleah Hampton (PhD candidate, School of History and Politics at the University of Adelaide) for their helpful insights into military tactics and the performance of the British Army during World War I. All errors and omissions remain the authors’ responsibility. 1 Lee D. Parker and Philip Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light: Lyndall Urwick's Scientific Management," Journal of Management History 17, no. 4 (2011): 379-98. 1 focus are then investigated. Historical constraints upon the perceived applicability of military metaphors to management theory and practice, and a changing set of contemporary military and business structures are finally reviewed. Urwick’s Career: Military and Civilian Lyndall Urwick was born the only son of a wealthy family of glove makers in Worcester England in 1891.2 He completed an undergraduate degree in history at Oxford University before entering the family firm, Fownes & Co, in 1912.3 An officer in the Territorial Army, Urwick was amongst the first to be called up in August 1914 and he fought in the British Expeditionary Force until an attack of enteritis and dysentery put him into hospital in November 1914.4 Urwick’s recuperation was protracted. Arrangements were made to send him to an assembly camp in Rouen where newly arrived recruits were being prepared before being dispatched to the front-lines. In May 1915, Urwick returned to front-line service on the Ypres salient and in August 1915 he became an acting Captain. Ongoing concerns about his health saw Urwick begin his progress through a succession of staff appointments. Between November 1916 and April 1917 Urwick commanded a Training Reserve Brigade in Dorset and in April 1917 he returned to France where he served as Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General.5 At war’s end, Major Urwick was responsible for rounding-up allied prisoners of war left to fend for themselves by the retreating Germans. A final post-war promotion ensured that Urwick, who had been mentioned in dispatches on three occasions and had merited the award of the Mons Star Medal (with Bar) and the Military Cross, left the armed forces with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.6 In 1919, Urwick was awarded an Order of the British Empire.7 Urwick returned to the family business of Fownes & Co where he determined to apply insights acquired serving in the armed forces.8 Urwick had been introduced to the works of Frederick Winslow Taylor in 1915 and developed an affinity for Taylor’s approach to business organization.9 In 1921, Urwick gave a paper at the Oxford Management Conference which so impressed the confectionary manufacturer Benjamin Seebohn Rowntree that he invited Urwick to reorganise the company’s sales and administrative offices.10 Encouraged by Rowntree, himself the publisher of an influential study of poverty, Urwick began to publish and speak on management matters and became acquainted with leading management 2 Michael Roper, "Re-Remembering the Soldier Hero: The Psychic and Social Construction of Memory in Personal Narratives of the Great War," History Workshop Journal, no. 50 (2000): 181-204. 3 Michael Roper, "Masculinity and the Biographical Meanings of Management Theory: Lyndall Urwick and the Making of Scientific Management in Inter-War Britain," Gender, Work & Organization 8, no. 2 (2001): 182204; Morgan Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management (Abingdon, 2003), 259-64. 4 For an account of Urwick’s early life see: Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64; Edward Brech, Andrew Thomson, and John F. Wilson, Lyndall Urwick, Management Pioneer: A Biography (Oxford, 2010), 13-21. 5 Brech, Thomson, and Wilson, Lyndall Urwick, Management Pioneer, 13-21. 6 Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64; Brech, Thomson, and Wilson, Lyndall Urwick, Management Pioneer, 13-21. 7 Ibid; Roper, "Re-Remembering the Soldier Hero." 8 Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64; Brech, Thomson, and Wilson, Lyndall Urwick, Management Pioneer, 13-21. 9 Brech, Thomson, and Wilson, Lyndall Urwick, Management Pioneer, 18. 10 Roper, "Masculinity and the Biographical Meanings of Management Theory," 186; Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64. 2 theorists such as Mary Parker Follett.11 In 1928, he left Rowntree’s employ to take up the position of Director of the International Management Institute in Geneva where he lived until the Institute’s demise in 1934.12 Returning to England, he co-founded Urwick, Orr and Partners, one of the largest and most influential management consultancies in the United Kingdom.13 Urwick was also one of British management’s most prolific writers and public speakers, authoring at least thirty books and hundreds of articles on the subjects of management, business organisation and business administration.14 Hannah has described Urwick as Britain’s “most consistent and coherent advocate of [industrial] rationalization” whilst others say he was the “driving force” behind the Administrative Staff College at Henley-on-Thames.15 His career also saw him hold visiting appointments at universities in Canada, the United States, and Australia where he died in 1983.16 Taylor’s Disciple Urwick retained a lifelong admiration for Taylor and his approach to management. In 1933, Urwick’s devotion to Taylor’s pursuit of a science of management was made clear: The curious feature of the industrial situation today is this. On the mechanical side of production, on the application of the resources of nature to the production of material goods, the scientific attitude is largely supreme. But on the much more important human side of management, the task of inducing men to cooperate, the conception of scientific method is often ignored.17 In the 1940s, writing with his co-author Edward Brech, Urwick continued to align himself with the Scientific Management project. They said Scientific Management applied: ...science to the problems of the direction and control created by the fact that discoveries in the physical sciences had modified profoundly the whole material circumstances of industrial work.... Scientific Management ... [is] ... thinking scientifically instead of traditionally or customarily about the processes involved in the control of the social groups who co-operate in production and distribution.18 Like many of his early twentieth-century contemporaries, the Soviet leader Vladimir Ilich Lenin included, Urwick found in Taylorism a conception of management that promised to 11 Roper, "Masculinity and the Biographical Meanings," 186. Ibid; Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64. 13 Roper, "Re-Remembering the Soldier Hero," 185; Roper, "Masculinity and the Biographical Meanings," 186; Witzel, Fifty Key Figures in Management, 259-64. 14 Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light," 381-82. 15 Leslie Hannah, The Rise of Corporate Capitalism (London, 1976), 33; Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage against the Dying of the Light," 382. 16 Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light," 381-82. 17 Lyndall F. Urwick, Management of Tomorrow (London, 1933), 24. 18 Lyndall F. Urwick and Edward Brech, Making of Scientific Management, vol. I (London, 1951), 9. 12 3 administer human effort in a manner that was as scientific as the technologies found in the twentieth-century factory.19 What makes Urwick unusual amongst his contemporaries is his continued expression of admiration for Taylor long after others were beginning to question the value of Scientific Management. The Human Relations School may have convinced others that strict adherence to Taylor’s principles imposed too high a price in absenteeism, unrest and conflict but not Urwick.20 His faith in Scientific Management never wavered.21 In 1969, Urwick was again praising Taylor’s “determination to break through [any] restriction of output”.22 He continued: The individual employed in an institution engaged in making and/or distributing goods and/or services ... is also a consumer.... To argue that ‘people’, i.e. the people employed in any economic institution, should come first and its purpose should be subordinated to their sentiments is ... ‘a moonbeam from the larger lunacy’. The business that is not organised on the principle that the consumer comes first is headed for bankruptcy.23 Throughout his life, Urwick retained his commitment to Taylor’s conception of a scientific approach to industrial administration because he believed such an approach would unleash the full productive potential of the technologies at industry’s disposal. Scientific Management reduced waste and inefficiency allowing the industrial worker the opportunity to share in an ever increasing quantity of goods and services being produced at progressively reduced cost. Industry should be made “as efficient as possible ... so that you are able to give to the workers an ever-rising standard of life”.24 The second theme that is striking about Uwrick’s writings is the extent to which he drew upon his experiences in the armed forces to illustrate the theoretical propositions he was seeking to express. Two military principles which recur in his work, and for which he became renowned, were the line-staff distinction and the span of control. Line and Staff Relationships and the Span of Control Urwick observed that “enormous ... modern armies” supply their commanders with “a regular staff of specially selected and trained officers” who “ensure smooth and efficient coordination of effort between all parts of the force”.25 Effective coordination was achieved by 19 See: James G. Scoville, "The Taylorization of Vladimir Ilich Lenin," Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 40, no. 4 (2001): 620-26; Daniel A. Wren and Arthur G. Bedeian, "The Taylorization of Lenin: Rhetoric or Reality?," International Journal of Social Economics 31, no. 3 (2004): 287-299. 20 Graham Sewell and Barry Wilkinson, "Someone to Watch over Me': Surveillance, Discipline and the Just-inTime Labour Process," Sociology 26, no. 2 (1992): 271-89, 276. 21 See: Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light." 22 Lyndall F. Urwick, "Management and ‘the American Dream’," SAM Advanced Management Journal 34, no. 3 (1969): 8-16, 11. 23 Ibid. 24 Urwick and Brech, Making of Scientific Management, 58. 25 Lyndall F. Urwick, The Elements of Administration, 2nd ed. (London, 1947), 75. 4 staff officers who acted on the commander’s behalf. He then drew upon this practice to suggest that in large organisations: Co-ordination ... cannot be separated from the functions and responsibilities of the leader.... It is logical to anticipate an increased specialisation of the leader’s duty of co-ordination through subordinates associated with him in a ‘staff’ relationship.26 His military inspired view of the role of staff managers stood in marked contrast to the commonly held view of the period. The latter defined ‘staff’ as functional specialists whose job it was to advise line managers. Urwick believed the proper role of staff managers was to assist the chief executive. Urwick wrote: Attempts so far ... in industry have been in nature a compromise between the necessity for specialisation ... and the necessity for preserving a direct line of authority.... These compromises have been described generically in industry as ‘the staff and line’ method of organisation.... In military life ... ‘staff’ is not applied either to those exercising authority and responsibility on a unitary basis – ‘the line’ - or those exercising authority and responsibility on a functional basis - specialised troops and administrative services.... It has been recognised that if the ... [chain of command] ... is to be secured no chief can delegate any of his authority or responsibility except through that process.... There has grown up a class of officers – ‘the staff’, who ... exercise their chief’s authority in assisting him to carry out his responsibilities of command. By graduations of authority and subdivision of work within the ‘staff’ there is built up a structure by which the chief can assure himself that all detailed consequences of any decision have been worked out, are understood, and are being carried out in correlation by everyone under his command, both specialists of all kinds and troops in the line. The authority of his line commanders is not interfered with ... [because] ... orders issued by the ‘staff’ are the chief’s orders....27 Staff managers should not exercise authority in their own right; but rather, act on the chief executive’s behalf. Urwick explained the distinction as follows: During 1917-1918 I had the opportunity to observe firsthand the organization of a British infantry division.... The Commander had ... only six immediate subordinates who usually approached him directly – the three Brigadiers General 26 27 Ibid., 76. Urwick, Management of Tomorrow, 64-65. 5 in charge of infantry brigades, the Brigadier General of Artillery and his two principle general staff officers. The latter were able to relieve the Commander of all the routine work of coordinating line and specialist activities. They did virtually all the paper work, drafting operational and routine orders, conducting correspondence, etc. However, the responsibility for every word they wrote was the Commanders; they had no personal authority.28 Urwick focussed on the military’s line-staff distinction because he believed conventional definitions encouraged the exercise of personal authority within a functionally defined area of expertise by staff managers. His First World War experience in the line and as a staff officer had taught him to distrust any source of authority located outside the chain of command; the reporting relationships that linked the commander to his subordinates in the line. The maintenance of this chain of command was vital if an organization was to maintain the unity of command and direction needed to coordinate action in the pursuit of goals. Thus, for example, Urwick suggested a personnel manager should be: Responsible directly either to the administrative authority (the board) or the chief executive officer ... [and] ... in direct (‘line’) control of all units in the organization specialising in various aspects of personnel work – employment, medical, welfare.... There are however three aspects of personnel work – general relations between the undertaking and its employees, trade union negotiation and [the] development and promotion of higher executives – which are of such character that they can only be handled effectively ... by the chief executive officer. Where a personnel manager assists a chief executive in the preliminary stages of such matters he should act in a ‘staff’ capacity.29 In addition to the line-staff distinction, Urwick was also known for the ‘span of control’, a phrase he coined in 1933, whilst he assisted on the translation of a paper for the Bulletin of the International Management Institute.30 Urwick explained: As far as I know, the first person to direct public attention to the principle of span of control was a soldier – the late General Sir Ian Hamilton. His statements ... [are] ... the basis for subsequent interpretations of the concept orientated to business.31 Urwick then went on to quote General Sir Ian Hamilton directly, “the average human brain finds its effective scope in handling three to six other brains”.32 Urwick often drew on military experience to assert that span of control was restricted to a small number of subordinates. For example: Lyndall F. Urwick, "The Manager’s Span of Control," Harvard Business Review 34, no. 3 (1956): 39-47, 46. Lyndall F. Urwick, Personnel Management in Relation to Factory Organization (London, 1943), 26-27. 30 Lyndall F. Urwick, "V. A. Graicunas and the Span of Control," The Academy of Management Journal 17, no. 2 (1974): 349-54, 351. 31 Urwick, "The Manager’s Span of Control," 39. 32 Ibid. 28 29 6 Obviously, the number of any individuals in any organization with whom a leader can have this direct official relationship is, save in the cases of the smallest businesses, an infinitesimal fraction of the whole.... It is important because of the importance of example. A chief of staff of the United States Army wrote a good many years ago – ‘The leader must be everything that he desires his subordinates to become. Men think as their leaders think, and men know unerringly how their leaders think’.33 In the latter half of his career, Urwick defended his preference for narrow spans of control against Herbert Simon’s contention that “Administrative efficiency is enhanced by keeping at a minimum the number of organizational levels” and that “the results to which this principle leads are in direct contradiction to the requirements of ... span of control”.34 In Urwick’s mind, Simon’s claim that the limits imposed by the span of control could be violated was mistaken. Alluding once more to the British Army he explained: There were 18 persons directly responsible to our Divisional Commander - a dozen more than we have said the ordinary business executive can effectively handle.... How had this apparently successful neglect of the principle of span of control been made to work? First of all, a clear distinction was drawn between the nominal right of direct access to the Commander and the frequent use of that right. Normally, heads of specialized branches, and indeed all subordinates, were expected to take up all routine business through the appropriate general staff officer in the first instance. Only if they regarded the matter as one of outstanding importance which justified them in approaching the Commander - and only after they had failed to secure a satisfactory settlement with one of his general staff officers - would the Commander accept a direct discussion.... The Commander had thus only six immediate subordinates who usually approached him directly.35 Simon had failed to appreciate that staff managers mediated the relationship between an executive and their subordinates. Sometimes an organization might use staff to give the appearance of a broad span of control; but, the limits imposed by the span of control were absolute. For any given number of subordinates; the number of managers, either line or staff, needed to supervise them adequately was always fixed. As late as 1974, Urwick continued to deny Simon’s claim that more than six subordinates could operate under a manager’s supervision. For some years I had been asserting that there was a strict limit to the number of direct subordinates an executive (any executive) should have. This opinion was based on 3 factors: 33 Lyndall F. Urwick, Leadership in the Twentieth Century (London, 1957), 9. Herbert A. Simon, Administrative Behavior (New York, 1947), 26-28. 35 Urwick, "The Manager’s Span of Control," 46. Italics in original. 34 7 1. My personal experience in the British Army as a regimental and staff officer between 1914 and 1918. 2. A passage in a book of reminiscences by the late General Sir Ian Hamilton entitled ‘The Soul and Body of an Army’, which I read about 1924. 3. Experience in industry at Rowntree & Co. Ltd., York, England, 19221928.... Since it was first published, this principle has suffered endless attack and misunderstanding.... Let me repeat it as ... [I] ... originally framed it, ‘No executive should attempt to supervise directly the work of more than five, or at the most six, direct subordinates whose work interlocks.36 Urwick’s determination to maintain the currency of the span of control in the face of challenge and apparent exceptions is a recurring feature of his philosophy and writings. It is a pattern identified by Parker and Ritson in their study of Urwick’s longstanding and consistent defence of Scientific Management over 60 years.37 It was not as if Urwick was an inflexible thinker who could not accommodate new ideas. This Taylorist had even welcomed Elton Mayo’s Hawthorne Studies and ranked them amongst Scientific Management’s greatest achievements.38 However, Urwick was dogged and unyielding in the defence of his core beliefs.39 Economic Decline To understand why Urwick remained such a committed devotee of Taylor and why he continued to deploy military metaphors it is necessary to view his career in its proper historical and economic context. Urwick was born in 1891, approximately the same time Britain lost its position as the world’s leading industrial economy to the United States.40 Tables 1 and 2 suggest that in the decade preceding his death in 1983, one could divide the countries of the developed world into two categories. There were those that had overtaken the United Kingdom’s economy on the global measure of gross domestic product per capita and those countries that would soon overtake it if historical growth rates persisted. Over his lifetime, the head start afforded to his native economy by the industrial revolution was slowly 36 Lyndall F. Urwick, "V. A. Graicunas and the Span of Control," 350. Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light." 38 See: Lyndall F. Urwick, Life and Work of Elton Mayo (London, 1960). Urwick rejected Douglas McGregor’s contention that managers had to choose between Scientific Management (Theory X) and the Human Relations School (Theory Y). See: Lyndall F. Urwick, "Are the Classics Really out of Date? A Plea for Semantic Sanity," SAM Advanced Management Journal 34, no. 3 (1969): 4-12; Lyndall F. Urwick, "Theory Z," SAM Advanced Management Journal 35, no. 1 (1970): 14-21. 39 Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light," 385-89. 40 See: Moses Abramovitz, "Catching up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind," The Journal of Economic History 46, no. 2 (1986): 385-406; Angus Maddison, Dynamic Forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View (Oxford, 1991), 24-25; Stephen N. Broadberry, "How Did the United States and Germany Overtake Britain? A Sectoral Analysis of Comparative Productivity Levels, 1870-1990," The Journal of Economic History 58, no. 2 (1998): 375-406. 37 8 eroded by persistent low rates of economic growth. Lieutenant-Colonel Urwick lived his life in the shadow of relative economic decline. INSERT TABLES 1 AND 2 ABOUT HERE Determining precisely why the British economy became one the developed world’s most sluggish industrial economies after 1870 is, according to the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, “the crucial question of British economic history”. 41 McCloskey argued any appearance of relative decline in the latter nineteenth century is more apparent than real.42 The law of diminishing returns simply reduced the reward afforded by further investment in the world’s leading industrial economy and its rate of growth fell as a consequence. 43 Others have suggested that McCloskey was wrong. They note that Britain was a net exporter of productive resources (both labour and capital) and make the claim that the domestic economy was starved of investment funds by an inefficient capital market’s addiction to low-risk foreign bonds.44 Hobsbawm blamed Britain’s status as the world’s first industrial power. As long as the established industries of the early industrial revolution made adequate profits the incentive to invest newer industries and technologies would be weak.45 Others claimed the public schools and Oxbridge promulgated gentlemanly values that dissipated the industrializing and entrepreneurial instincts needed to sustain the industrial revolution.46 Olson claimed late-nineteenth century Britain was simply the victim of its own success. Political stability and affluence fostered distributional coalitions, rent-seeking alliances of self-interested individuals, which undermined the efficient operation of Britain’s markets.47 Finally there were those who blamed the City of London. The City had invested too much money abroad48 and denied British industry the protection and assistance that could only be provided by a large interventionist state.49 41 Eric J. Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day (London, 1969), 149. Donald N. McCloskey, "Did Victorian Britain Fail?," The Economic History Review New Series 23, no. 3 (1970): 446-59; Donald N. McCloskey, "Editor's Introduction," in Essays on a Mature Economy: Britain after 1840, ed. Donald McCloskey (Princeton, 1971); Donald McCloskey and Lars G. Sandberg, "From Damnation to Redemption: Judgments on the Late Victorian Entrepreneur," Explorations in Economic History 9, no. 1 (1971): 89-108; Donald N. McCloskey, "No It Did Not: A Reply to Crafts," The Economic History Review New Series 32, no. 4 (1979): 538-41. 43 See also: Abramovitz, "Catching up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind." 44 Nicholas F. R. Crafts, "Victorian Britain Did Fail," The Economic History Review New Series 32, no. 4 (1979): 533-37; William P. Kennedy, "Economic Growth and Structural Change in the United Kingdom, 18701914," The Journal of Economic History 42, no. 1 (1982): 105-114; William P. Kennedy, Industrial Structure, Capital Markets, and the Origins of British Economic Decline (Cambridge, 1987). 45 Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, 157-58. 46 Corelli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London, 1972); Martin J. Wiener, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, Second ed. (Cambridge, 2004). 47 Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities (New Haven, 1982). 48 William P. Kennedy, "Foreign Investment, Trade and Growth in the United Kingdom, 1870-1913," Explorations in Economic History 11, no. 4 (1974): 415-44; Kennedy, "Economic Growth and Structural Change in the United Kingdom, 1870-1914."; William P. Kennedy, Industrial Structure, Capital Markets, and the Origins of British Economic Decline; Sidney Pollard, "Capital Exports, 1870–1914: Harmful or Beneficial?," The Economic History Review New Series 38, no. 4 (1985): 489-514. 49 S. G. Checkland, "The Mind of the City, 1870-1914," Oxford Economic Papers New Series 9, no. 3 (1957): 262-78, 262-64; Andrew Gamble, Britain in Decline: Economic Policy, Political Strategy and the British State (London, 1981), 134; P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, "Gentlemanly Capitalism and British Expansion Overseas II New Imperialism, 1850-1945," The Economic History Review New Series 40, no. 1 (1987): 1-26, 3-6; E. H. H. Green, "Rentiers Versus Producers? The Political Economy of the Bimetallic Controversy c. 1880-1898," 42 9 Alfred Chandler had his own perspective on British economic decline. He argued that the prime contributors to economic growth during the late-nineteenth and the twentieth century were the industries of what David Landes called the second industrial revolution.50 Capital-intensive production technologies characterized by high fixed and sunk costs were common, which imbued large producers capable of realizing economies of scale and scope with first-mover and competitive advantages.51 To realize economies of scale and scope, firms had to acquire large manufacturing facilities, establish the marketing and distribution networks, and, recruit and train professional managers to plan for and coordinate large scale manufacturing, marketing and distribution. The result, Chandler said, was a corporate form of capitalism, one dominated by oligopolistic market structures and the separation of ownership and control. Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ of the market had gone into retreat due to an increase in the amount of economic activity coordinated by the ‘visible hand’ of managerial planning and control. Chandler also compared the faster growing industrial economies of pre-World War I America and Germany with its sluggish British counterpart.52 In Germany, he said, industry had developed in much the same way as it had in America. Large firms under professional management captured first mover advantages in industries like chemical, mechanical and electrical engineering. However, in Britain Chandler discovered a preponderance of smallto-medium sized firms managed by their founding entrepreneurs and their immediate family. The British had failed to invest in manufacturing facilities, marketing and distribution and professional management and for that reason they could not realize the economies of scale and scope. In Britain, the ‘invisible hand’ of market competition continued to allocate resources because arms-length exchange linked manufacturers with their sources of supply whilst independent merchants and wholesalers distributed product to the consumer. Relative industrial decline, Chandler said, had its origins in a uniquely British commitment to an owner-managed form of personal capitalism. The English Historical Review 103, no. 408 (1988): 588-612, 607-12; Scott Newton and Dilwyn Porter, Modernization Frustrated: The Politics of Industrial Decline in Britain since 1900 (London, 1988), 10; Sidney Pollard, Britain's Prime and Britain's Decline: The British Economy 1870-1914 (London, 1989), 257-58. 50 David S. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to Present, Second ed. (London, 2003), 235; Alfred D. Chandler, "Organizational Capabilities and the Economic History of the Industrial Enterprise," The Journal of Economic Perspectives 6, no. 3 (1992): 79-100, 81. 51 Alfred D. Chandler, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, Mass., 1977); Alfred D. Chandler, "Institutional Integration: An Approach to Comparative Studies of the History of Large-Scale Business Enterprise," Revue Économique 27, no. 2 (1976): 177-99; Alfred D. Chandler, "The Growth of the Transnational Industrial Firm in the United States and the United Kingdom: A Comparative Analysis," The Economic History Review New Series 33, no. 3 (1980): 396-410; Alfred D. Chandler, "The Emergence of Managerial Capitalism," The Business History Review 58, no. 4 (1984): 473-503; Alfred D. Chandler, "The Enduring Logic of Industrial Success," Harvard Business Review 68, no. 2 (1990): 130-40; Chandler, "Organizational Capabilities and the Economic History of the Industrial Enterprise."; Alfred D. Chandler and Takashi Hikino, Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, Mass., 1990). 52 Chandler and Hikino, Scale and Scope. 10 Elbaum and Lazonick drew upon Chandler’s concepts to account for the performance of the British economy after World War I.53 They argued that as the twentieth century progressed, Britain’s inability to master managerial planning and control continued to undermine economic growth. The industrial economy obtained the outward appearance of Chandlerian corporate capitalism due to inter-war and post-Second World War mergers that induced an increase in firm size. But, British industry continued to suffer from the legacy of its small-firm and market-oriented past. What British industry had needed, they said, was “the visible hand of coordinated control” and that in the “absence of leadership from within private industry, increasing pressure fell upon the state”.54 Labour governments responded by turning to dirigisme, a policy of national economic planning on the French model. However, what had been needed was a corporatist reform program and tariff protection on a scale never before seen in Britain under peace-time conditions.55 British dirigisme proved no match for the industrial economy’s underlying competitive weaknesses. In 1979, many British voters were looking backwards to the Victorian era of laissez faire with nostalgia because governments and industry had failed to come to terms with the technological realties of the second industrial revolution. Britain elected a Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher that was determined to re-establish the supremacy of the market. Thatcherism merely compounded industry’s problems, which in turn accelerated the deindustrialization of the British economy. The Failings of Practical Men Like Chandler, Urwick was in no doubt that the need for professional management in organizations stemmed from a technologically induced increase in the size of industrial firms.56 He also shared with Chandler and Elbaum and Lazonick the view that manufacturing in Britain was too poorly integrated to compete with its foreign counterparts. In 1929, for example, Urwick was expressing the distinctly Chandlerian view that industry needed to: …improve the general organization of production and distribution on national … lines by elimination of waste, simplification and standardization, [and] horizontal and vertical combinations.57 However, Urwick believed that British industry was particularly disadvantaged by a unique cultural trait. The British, he said, had an innate distrust of theoretical insight because they valued practical knowledge above all else. In 1943, Urwick claimed: 53 See: Bernard Elbaum and William Lazonick, "The Decline of the British Economy: An Institutional Perspective," The Journal of Economic History 44, no. 2 (1984): 567-83; Bernard Elbaum and William Lazonick, eds., The Decline of the British Economy (Oxford,1986); Bernard Elbaum, "Cumulative or Comparative Advantage? British Competitiveness in the Early 20th Century," World Development 18, no. 9 (1990): 1255-72; Maurice W. Kirby, "Institutional Rigidities and Economic Decline: Reflections on the British Experience," The Economic History Review New Series 45, no. 4 (1992): 637-60. 54 Bernard Elbaum and William Lazonick, "An Institutional Perspective on British Decline," in The Decline of the British Economy, ed. Bernard Elbaum and William Lazonick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 1011. 55 Kirby, "Institutional Rigidities and Economic Decline," 652. 56 Urwick, Leadership in the Twentieth Century, 4-5; Urwick, Life and Work of Elton Mayo, 7-14. 57 Lyndall F. Urwick, The Meaning of Rationalization (London, 1929), 19. 11 It has been observed that ‘If you hear an Englishman say that A is a theorist and B a practical man, you know he would prefer B for a son-in-law’. Great Britain is probably the only country in the world in which the title of Professor is a term of reproach.... Undoubtedly in the past our habit of treating theory with skepticism and giving support only to practices well tried in the furnace of events has enabled us to avoid many dangers and disappointments.... In matters of social organization we have been a nation of craftsmen.... We have toiled manfully at the bench, meeting each new difficulty as we encountered it, rather by trial and error than by any extraordinary flight of the imagination... This country was the first to adopt modern mechanized industry.... We must recognize that we have not hitherto succeeded in controlling the energies released by the Industrial Revolution, and the primary question of our time, the question which faces all of us, is – Can we develop and adequate intelligence which will enable us to do so?58 Elsewhere Urwick suggested the British were “an obstinately practical community [that] eschewed the … path of general ideas and confined itself to … the solution of practical problems”.59 He continued: To discuss administration in terms of principle [before a British audience] is therefore an undertaking of some temerity. It must inevitably encounter the impatience of so-called ‘practical men’ with theory, with ideas…. [However] lack of administrative skill can only be cured by persuading administrators to become more skilful. And the root of any real progress in this direction must necessarily lie in ideas … [and] … theory.60 In 1968, he addressed the Australian Institute of Management and told his audience that Australia’s great misfortune had been to model its universities on those of Great Britain rather than the United States.61 Australia had inherited Britain’s tendency to put responsibility for managerial education and research outside the academies beyond the reach of those who most valued theoretical and scientific insight. No doubt, Urwick would have sympathised with John Maynard Keynes’ claim that “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”.62 For Urwick, a disdain for theory and 58 Lyndall F. Urwick, "Administration in Theory and Practice," British Management Review 8, (1943): 37-59, 37-38. 59 Urwick, The Elements of Administration, 13. 60 Ibid., 13-14. 61 Lyndall F. Urwick, The Fifteenth William Queale Memorial Lecture: Learning and Leadership (Adelaide, 1968), 16-20. 62 John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Money and Interest (New York, 1964), 383. 12 science retarded the quality of British management because new ideas were needed to maximise the productive potential of the technologies of the day. No doubt, his personal commitment to Taylorism reflected a hope that one day Scientific Management might cure the British of their habitual pragmatism. The Martial Origins of Management If Uwrick had identified in Scientific Management an ideal prescription for British pragmatism, the question remains as to why Urwick was equally certain that the British Army’s organizational hierarchy represented ideal managerial structure within which Scientific Management should be practiced? Chandler claimed that the American economy’s first managerial hierarchies emerged on the railroads and that these structures became the blueprint for America’s managerial revolution.63 However, Chandler also assumed that these managerial structures had simply emerged in response to the technologically imposed demands of the day. It was Hoskin and Macve who later returned to the American railroads to suggest that a prime mover in the development of their managerial structures had been George W. Whistler. 64 Whistler was a former army engineer and a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Hoskin and Macve’s analysis, which drew upon Michel Foucault for theoretical inspiration, suggested that at West Point Whistler absorbed a surveillance-based and disciplinary mode of organization and subsequently deployed it to turn the railroad’s employees into a malleable and obedient workforce. However, one need not be a devotee of Foucault to concede that the railroads and their second industrial revolution successors encountered organizational problems that were at least similar to, if not identical to, problems first encountered by the conscripted mass-armies of eighteenth and early nineteenth century continental Europe. 65 In both cases, large numbers of functionally defined specialists depended upon a coordinating command system to plan for and control their activities. Indeed the latest, and perhaps most comprehensive, account of the American transcontinental railroads suggests that those railroads’ founders were indeed drawn to military modes of organization to supply a viable alternative to the market to coordinate economic activity. 66 It seems likely that those who administered the world’s first large business organizations felt an affinity for military systems of organization.67 Urwick was explicit in his admiration for precedents set by the military. Nevertheless, he also noted that many of his contemporaries were resistant to the notion that military practice could inform industrial organization. Unusually for Urwick, who rarely criticized Frederick Taylor, Urwick blamed Taylor for this state of affairs. Urwick wrote: 63 Alfred D. Chandler, "The Railroads: Pioneers in Modern Corporate Management," The Business History Review 39, no. 1 (1965): 16-40. 64 Keith Hoskin and Richard Macve, "Understanding Modern Management," University of Wales Business and Economics Review 5, (1990): 17-22. 65 Philip A. Talbot, "Management Organisational History–a Military Lesson?," Journal of European Industrial Training 27, no. 7 (2003): 330-40, 335-36. 66 Richard White, The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York, 2011), 281-82. 67 Richard R. John, "Elaborations, Revisions, Dissents: Alfred D. Chandler, Jr's, ‘the Visible Hand’ after Twenty Years," The Business History Review 71, no. 2 (1997): 151-200, 185. 13 An influence making for distrust of military forms of organization amongst businessmen ... may have been the writings of Frederick Winslow Taylor, ‘the father of scientific management’.... In using ‘military’ as a descriptive of the form of organization he was trying to displace, Taylor was thinking about two different things: organization, or the structure of authentic communication, and the way in which authority is exercised. He repeatedly emphasized the need for a change of attitude on the part of foremen. The authoritative approach ... was to be replaced by an attitude resembling that of a good teacher.... Taylor had a very strong dislike of the authoritarianism and rigidity of the Prussian military code of the nineteenth century. When sixteen he was in Berlin ... during the Franco-Prussian War. As a young child he had experienced the Civil War. He shared with ... [his] ... generation the horror felt by every person of intelligence at the thought of war as a means of settling human differences. But he was innocent of any direct experience with the military organization of his own or any other democratic country. Had he had such direct experience, he would have realized that military organization faces exactly the same problem that business organizations do ... though its solution differs from that in business, because experience has made it more sensitive to the need for maintaining a clear-cut system of communication. But this is a requirement common to both forms of organization, quite separate and distinct from the need in military operations for an authoritative and rigid code of discipline.... In describing as ‘military’ the system common in American machine shops in the 1880’s ... Taylor was inaccurate. What was in his mind was the authoritarian character of military disciple rather than the military form of organization with which he had little acquaintance.68 The modern industrial firm should be structured like a military force, Urwick said, because the organization of modern manufacturing demanded that activities be coordinated in a rational and unified manner. The life of an industrial worker differed from that of the soldier in only one material respect. Business competition lacked the capacity to impose the urgent and immediate risks to life and limb found on the battlefield and so military discipline was unnecessary, impractical and undesirable in a business organization.69 The industrial manager did not need, and should not seek, the military officer’s power to induce instant obedience. There is another reason, aside from its underlying relevance, that would have accounted for Urwick’s affinity with the British Army’s organizational hierarchy. As a former line and staff officer, he was familiar with the British Army’s organizational structure and he had 68 69 Lyndall F. Urwick, Staff in Organization (New York, 1960), 58-60. Ibid., 60-66. 14 witnessed that army’s transformation following the Somme in 1916. By 1918, the British Army ranked amongst the most effective fighting forces in the world. An Army Transformed In 1916, the British Army had three inherent disadvantages to overcome. The first was inexperience. Unlike the continental powers, nineteenth-century Britain had been a largely demilitarized society which maintained a small military force made up of professional volunteers.70 When the war began, Lord Kitchener advised the government to build Britain’s first mass army and inevitably the volunteers, and later the conscripts, who entered Kitchener’s Army needed time to adjust to the realities of modern warfare. 71 The second disadvantage was strategic. Traditionally, the British had left others to fight on the continent whilst it deployed its naval strength to attack its enemies’ interests on the peripheries.72 However, in 1916 Germany occupied vast amounts of Belgian and French territory and she seemed too powerful an opponent to be defeated by the French and the Belgians alone. The British Army felt obliged to attack the German defensive positions in Western Europe.73 The third disadvantage was tactical. The military technologies of the day increased the inherent advantage usually afforded to defensive warfare. If they attacked, the British were going to have to move across battlefields dominated by efficient killing machines like machine guns and modern artillery.74 These three disadvantages combined to deadly effect when the British launched their assault on the German positions near the River Somme on 1 July 1916. That date remains the blackest in British military history because nearly 20,000 soldiers lost their lives. 75 The received wisdom regarding the first day of the Battle of the Somme is that thousands of British troops carried 66 lbs. of equipment and marched slowly to their deaths.76 However, Prior and Wilson’s seminal account highlights the enormity of the task confronting Britain’s inexperienced army on that day.77 Many units in the first wave moved into no-man’s land early and rushed forward in a desperate attempt to cross no-man’s land quickly once the preliminary barrage ended. Some even succeeded because on occasion the German defensive system was penetrated. Nevertheless, the majority of the advancing British infantry were simply cut down by a hail of bullets whilst enemy artillery rained down from overhead to create a killing zone that stretched for thousands of yards. Indeed, many British soldiers did not even make it to their own trenches because around 30 per cent of the British casualties were inflicted behind the British lines.78 No army would have emerged from the ordeal unscathed because the preliminary artillery barrage, which was supposed to suppress the German defences, had failed to achieve its objectives. 70 Edward M. Spiers, The Late Victorian Army, 1868-1902 (Manchester, 1992). John Terraine, White Heat: The New Warfare, 1914-1918 (London, 1982), 134-39. 72 Basil H. Liddell Hart, A History of World War, 1914-1918 (London, 1930), 13-38. 73 Gary Sheffield, Forgotten Victory (London, 2001), 63, 77-86. 74 Paddy Griffith, Battle Tactics on the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack, 1914-1918 (London, 1994), 20-44. 75 Prior and Wilson give a figure of 15,000 but this figure eludes the 3,000 deaths incurred in the diversionary attack on Gommecourt on the same day. Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Command on the Western Front: The Military Career of Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1914-1918 (Oxford, 1992), 177. 76 See: Liddell Hart, A History of World War, 315. 77 Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, The Somme (Sydney, 2005), 112-18. 78 Ibid., 116. 71 15 This is no place to document all the improvements introduced into the British Army between 1916 and 1918. Nevertheless, three significant improvements were made. First, the British determined that the casualties taken on the Somme were unsustainable. More weapons, not necessarily more men, would be needed to defeat the Germans. The Ministry of Munitions ensured British factories delivered artillery and “tanks, machine guns, Lewis guns, trench mortars, smoke, gas and above all high explosive shells” in ever increasing quantities.79 To use a business analogy, the British Army economized on the expenditure of human resources (casualties) by becoming more capital intensive. In 1918, for example, the Commander of the Fourth Army wrote “bearing in mind the limitations of our man-power” what was needed was “All possible mechanical devices in order to increase the offensive power of our divisions”.80 Second, science improved the performance of the equipment available. In this category, the efforts made to improve the artillery are most instructive.81 Tables were developed which explained how to compensate for the wear on a gun’s barrel and changing meteorological conditions. Accurate maps located the exact position of each gun on the surface of the earth whilst sound ranging, flash spotting and aerial reconnaissance pinpointed the exact position of enemy guns. The result was that British gunners perfected the art of predictive firing, which meant they could hit any target on the battlefield whilst remaining silent until zero-hour. This preserved for the attacking infantry the vital element of surprise. The final improvement was administrative. As line and staff officers gained experience, responsibility was delegated to lower levels in the chain of command. 82 The army’s senior commanders became more effective as their “sphere of ... activities” diminished to match “the limits of ... [their] ... capabilities.”83 In addition, decentralization meant the time needed to plan attacks shortened whilst the British became more adept at coordinating artillery, infantry and (on occasion) tanks in battle.84 1918 begun badly for the allies after the Germans launched an offensive in March designed to finish the war before American participation changed the balance of power.85 Given the static nature of the Western Front over the previous two years, the gains made by the Germans between March and July 1918 looked impressive. In reality, German tactical thinking had made a fetish of advance to the exclusion of strategic and operational considerations. “Don’t talk to me about strategy, I hack a hole, the rest follows” the German Commander Erick Ludendorff boasted; but, by July 1918 a heavily depleted German Army was operating on an elongated front at the end of lines of supply stretched to breaking-point.86 As the German offensive ground to a halt, the allies launched their counteroffensive. 79 Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 291. Henry Rawlinson quoted in Ibid. 81 See: Terraine, White Heat, 217, 307-08; Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 292-95; Griffith, Battle Tactics on the Western Front, 133-58; Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, 118. 82 Tim Travers, How the War Was Won: Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front, 1917-1918 (London, 1992), 176; Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front: The Military Career of Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1914-1918, 397. 83 Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 305. 84 Gary Sheffield, "Finest Hour? British Forces on the Western Front in 1918," in 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History, ed. Ashley Ekins (Auckland, 2010), 64-66. 85 Robert T. Foley, "From Victory to Defeat: The German Army in 1918," in 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History, ed. Ashley Ekins (Aukland, 2010), 69-70. 86 Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 89-90, 284; Foley, "From Victory to Defeat," 81. 80 16 The British Army’s participation in the counteroffensive campaign of 1918 falls into two phases. During the first phase, it drove the German force in front of it from one improvised defensive position to the next back to its starting point on the Hindenburg Line. 87 Then in September and October, a British force attacked the Hindenburg Line itself. Begun in 1916, the Hindenburg Line had been built to strengthen the German’s defensive position in the West and after the Germans took up residence in 1917 they continued to add to its defences. 88 As late as summer 1918, the Germans were incorporating the former British trenches overrun in March into their defensive system.89 Concrete bunkers, machine gun emplacements, barbed wire, tunnels, trenches, dug-outs and command posts created a defensive zone 6,000 yards deep and in the sector chosen for the British attack the St Quentin Canal created an additional barrier.90 It was one of the best prepared defensive positions encountered by any army on the Western Front. The British assault on the Hindenburg Line began with an attack on the outpost line on 18 September 1918.91 The battle proper began on 29 September.92 By 5 October, the British had broken through the last line of defence and were pursuing the German across open country once more.93 The reversal in relative fortunes of the British and Germans since the Somme could not have been more complete. The Germans were now reduced to a state of impotence. Prior argues: No infantry whether well trained or ill could withstand the maelstrom [inflicted by the British on the Hindenburg Line]. The defenders were either buried, or killed, or rendered incapable of fighting or they fled.... By a combination of a superior weapons system ... or by sheer volume of munitions available ... the British had the means to defeat any defensive combination thrown against them by the Germans. This means that whatever stratagems the Germans now applied in the field, the British could outdo them. The German military machine ... [was] ... battered and bludgeoned and harried and hammered and crushed by the British....94 The victories of 1918 must have played their part in Urwick’s advocacy of the British Army’s organizational structure. Science and the latest military technologies had given the British Army a combined arms weapons system that simply overwhelmed the Germans in 1918. Overseeing the transformation had been an administrative hierarchy that had become increasingly proficient as it gained in experience. Urwick returned to civilian life convinced that a similar transformation in the fortunes of Britain’s antiquated and mismanaged industrial economy might be possible. In Elements of Administration, Urwick tried to evoke his sense of post-war optimism when he wrote: 87 Travers, How the War Was Won, 110-57. Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 348-51. 89 Ibid., 348. 90 Ibid., 346-48; Robin Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," in 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History, ed. Ashley Ekins (Auckland, 2010), 49. 91 Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 354. 92 Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 49. 93 Prior and Wilson, Command on the Western Front, 379. 94 Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 50. 88 17 One of the advantages to be snatched from the disaster of a great war is that problems are stripped of the verbiage and the conventions and the wishful thinking of ordinary times. It is so with ... planning.... [It] is impossible to plan economic life in a world dependent on power-driven machinery unless production is simplified and standardised.95 If industrial administration really had military origins, then post-war demobilization was a unique opportunity for the British. For the first time, the majority of a generation of males had experienced military service. Between 1914 and 1918, over 6,000,000 British residents served in the armed forces, which equates to 58 per cent of all Englishmen, Welshmen and Scotsmen between the ages of 15 and 49 and 15 per cent of all Irishmen in the same age group.96 A similar thing had happened at the start of the second industrial revolution in the United States when the veterans of the Civil War of 1861-1865 returned to civilian life. In total, 2,000,000 residents of America’s industrial heartland in the North served in the Union Army; approximately 80 per cent of all males born in the Union states between 1837 and 1845 and 11 per cent of America’s total population saw service in either the Union or Confederate armies.97 In the case of Germany, military service was woven into the fabric of civilian life by a conscription system that required able bodied males of military age serve in the regular army and then released them into the civilian population where they constituted a reserve available for mobilization in times of war.98 Military service was a civic obligation. Civil war and conscription had given the early second industrial revolution industries of America and Germany ample opportunity to absorb organizational insights from their armed forces. The British had to wait until the end of the Great War for a similar opportunity. Britain’s Forgotten Victory The paradox is that Urwick felt the need to go into print to extol the virtues of military organization to an audience that contained the first generation of British managers to have actually served in the armed services. Why did Urwick feel the need to introduce the British to the principles of military organization when an unprecedented number of British managers, and the workers they were supervising, had actually seen service? The answer to that question lies in post-war Britain’s collective memory of the First World War. Within weeks of the British breakthrough on the Hindenburg Line, the British achievement was being undermined by the events in the forest of Compiègne on 11 November 1918. Fearing that impending military collapse might lead to an allied invasion of Germany, the German High Command dispatched representatives to seek an end of hostilities with the Supreme Commander of Allied Armies.99 The instrument signed by the German representatives was euphemistically called an ‘Armistice’, as if two sides of approximate 95 Urwick, The Elements of Administration, 29. Jay M. Winter, "Britain's `Lost Generation' of the First World War," Population Studies 31, no. 3 (1977): 44966, 450-52. 97 Dora L. Costa and Matthew E. Kahn, "Cowards and Heroes: Group Loyalty in the American Civil War," Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, no. 2 (2001): 533-37, 527-29. 98 See: Meyer Kestnbaum, "Citizen-Soldiers, National Service and the Mass Army: The Birth of Conscription in Revolutionary Europe and North America," Comparative Social Research 20, (2002): 117-44; Daniel Moran and Arthur Waldron, The People in Arms: Military Myth and National Mobilization since the French Revolution (Cambridge, 2006). 99 Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 51-53. 96 18 parity negotiated an end to the war. In truth, there had been no negotiations and this Armistice actually amounted to a German surrender on terms. 100 Nevertheless, the reality of German defeat in 1918 was already being obscured. In the following years, several myths developed that further obscured the reality of allied victory in the 1918.101 The first was that on 11 November 1918 an undefeated Germany had sought a mild peace, disarmed and was then ambushed at Versailles where the allies imposed an unexpectedly harsh peace. In truth, the allies had made their intentions at any future peace conference abundantly clear to the Germans before November 1918. The Treaty of Versailles contained little that had not been signalled by the terms of the Armistice. Nevertheless, the myth that President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points tricked an undefeated enemy into laying down its arms persisted.102 Yet another myth was that the origins of the German defeat lay not on the battlefield.103 On one level, this myth evoked the allied blockade to claim the German economy had been denied access to the resources needed to sustain its armed forces and feed its population.104 In Britain, still Europe’s leading maritime power, many felt a natural affinity for the claim that the Royal Navy had made a decisive contribution to winning the war.105 On another level, a far more sinister myth emerged. Germany was undone by subversive forces; an alliance of Jews, communists, socialists and pacifists who fermented revolution at home.106 At first, this claim only resonated with anti-Semites and nationalists on the extreme right of German politics.107 By the 1930s, Adolf Hitler was proclaiming to the world that “Britain and France did not defeat us on the battle-field, that is a lie” whilst his followers persecuted those accused of having “stabbed” Germany “in the back”. 108 Civil unrest “had been a consequence, not a cause” of military defeat; but, National Socialist propaganda further obscured the reality of allied victory in 1918.109 The claim that allied victory had been due to trickery, blockade and insurrection obscured the reality that the British Army had out performed its German opponent in 1918. That army’s reputation was further damaged by developments in British popular culture. Blackadder Goes Forth, the Donkeys and Goodbye to All That! In the late 1980s, Ben Elton and Richard Curtis scripted Blackadder Goes Forth a BBC television situation comedy set in the World War I trenches. 110 It portrayed the First World War British Army as an irrecoverably incompetent institution, one whose only contribution to the war was its capacity to waste the lives of British soldiers in futile attacks. As Badsey 100 Ibid. Ibid. 102 Les Carlyon, The Great War (Sydney, 2006), 472-74; Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 51-52. 103 Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 52. 104 David Stevens and James Goldrick, "Victory at Sea, 1918," in 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History, ed. Ashley Ekins (Auckland, 2010), 192-93. 105 Ibid. 106 Carlyon, The Great War, 765-66. 107 Prior, "Stabbed in the Front," 52. 108 Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, 221-22. 109 Ian Kershaw, Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris (London, 1998), 97. 110 For an account of the series and its relationship to the popular memory of the First World War in Britain see: Stephen Badsey, The British Army in Battle and Its Image: 1914-1918 (London, 2009), 37-54. 101 19 explains, “the dark idea of waiting to die ... gives the series its underlying structure”.111 It was also enormously popular with British audiences, in part because it mined the cultural inheritance that is Britain’s collective memory of the First World War. On the British stage and in film, events on the Western Front have been depicted as either tragedy or farce in productions like Journey’s End (1929) and the 1960s musical Oh What a Lovely War.112 Siegfried Sassoon’s novel Memoirs of a Fox Hunting Man (1928) focused on the lost innocence of the enthusiastic enlistee whilst Robert Graves’ Good Bye to All That (1929) presented the war as a futile exercise in destruction and slaughter.113 The British literary emphasis on the war as a senseless tragedy has been perpetuated by an education system that demanded generations of British school children spend more time learning about the First World War in English classes from the ‘war poets’ than actually studying its progress under the supervision of their history teachers.114 That said, popular history also did the British war effort a great disservice. In the 1930s, Basil Liddell Hart told British audiences that they fought the wrong war in the West and would have been better served concentrating their efforts on the Middle East and around the Mediterranean Sea.115 Alan Clark’s Donkeys (first published in 1961) was titled to evoke an unattributed German claim the British were ‘lions led by donkeys’. It amounted to a scathing attack on the quality of British generalship.116 Britain’s best-known British television historian in the 1960s, A. J. P. Taylor, claimed the war had been devoid of all moral principle; it was “War by timetable”, a conflict that started by mistake.117 Most importantly, there was the emphasis on the Somme and Passchendaele, where the British Army made disappointing progress, which came to dominate the British popular memory of the First World War.118 The idea that far too many lost their lives because their uncaring commanders were incompetent became the conventional wisdom in Britain.119 Urwick’s great failing was his inability to understand that his military metaphors were being received by a British audience that was beginning to perceive the war as a mismanaged national tragedy. As the victories of 1918 disappeared from the public consciousness, those who had administered the British Army during the war increasingly became the subjects of criticism and ridicule. British managers and industrial workers would have felt no desire to replicate an organizational hierarchy that had placed ‘donkeys’ in command of ‘lions’. Nothing illustrates Urwick’s inability to come to terms with the popular conception of World War I better than his ongoing references to General Sir Ian Hamilton. Hamilton may have known that human beings operate under supervisory limits; but, his public reputation was destroyed by the Dardanelles campaign of 1915.120 Surely, Urwick would have been better 111 Ibid., 47. Ibid., 47-51; Stephen Badsey, "Ninety Years On," in 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History, ed. Ashley Ekins (Auckland, 2010), 245. 113 Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs of a Fox Hunting Man (London, 1928); Robert Graves, Good Bye to All That (London, 1960). See also: Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, 7. 114 Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, 14-15. 115 Liddell Hart, A History of World War. 116 Alan Clark, The Donkeys (London, 1991). 117 Alan J. P. Taylor, The First World War an Illustrated History (London, 1963), 11-15. 118 Badsey, "Ninety Years On," 245. 119 Prior and Wilson, The Somme, 118; Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, 3. 120 Carlyon, The Great War, 43-44. 112 20 served if he had found other precedents for the span of control concept than the general many blamed for the failure at Gallipoli. Conclusions In Chandler’s analysis, the second industrial revolution had been a collectivized age. Managerial planning, control and coordination realized economies of scale and scope in large industrial manufacturing businesses. It was an era in which metaphors drawn from large military forces had particular relevance for business administration and this is why Urwick drew upon his First World War experiences. He saw in those experiences an opportunity to improve British managerial practice. However, it is unlikely the First World War metaphors Urwick utilized would have much currency for management today. As Langlois has noted, the last 30 years has seen the retreat of Chandlerian industrial firms in the face of ongoing technological change.121 Flexible, adaptive and affordable technologies have reduced fixed and sunk costs to the point where the capacity to realize economies of scale and scope is no longer a key determinant of organizational success. Indeed, the last three decades have witnessed an unrelenting winding-back of Chandler’s investments in productive capacity, distribution and management by means of outsourcing, downsizing and business process reengineering. The ‘invisible hand’ of the market coordinates the vast bulk of economic activity once more. The result is that industrial manufacture in the networked organizations of today bears an uncanny resemblance to a form of military organization unknown to Urwick; ad hoc and temporary military forces created specifically to meet the demands of a particular mission which have characterized battlefields since the end of World War II.122 Nevertheless, Urwick remains an important figure in the history of British industrial administration. In Urwick’s continued advocacy of Taylorist principles and his unique conception of the Scientific Management project, we see evidence that industrial practice in British manufacturers lagged behind that of many of its competitors. Urwick’s version of Scientific Management was broad-based and all-encompassing because he felt instinctively that in an industrial economy populated by practical men there was a need to teach the firstprinciples expounded by Taylor alongside insights drawn from early behaviourists like Mary Parker Follett and Elton Mayo.123 Similarly, Urwick’s advocacy of military hierarchies suggests a chaotic distribution of supervision and authority in British industry. During the war, the British Army had decentralized decision-making authority without jeopardising its capacity for coordinated action. In the army’s use of line and staff officers and its narrow spans of control, Urwick identified a means by which overburdened chief executives could delegate responsibilities to trained specialists whilst ensuring those subordinate to those executives remained subject to proper supervision. Urwick’s championing of the military metaphor of management reflects parallels and insights drawn from British military experience between 1914 and 1918. Its failure to gain traction reflects a subsequent historical societal reconstruction and reinterpretation of British military experience as ‘failure’ to create a climate less than conducive to Urwick’s ideas. As 121 Richard N. Langlois, "The Vanishing Hand: The Changing Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism," Industrial and Corporate Change 12, no. 2 (2003): 351-85; Richard N. Langlois, The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism: Schumpeter, Chandler, and the New Economy (Oxford, 2007). 122 Talbot, "Management Organisational History–a Military Lesson?." 123 Parker and Ritson, "Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light." 21 Parker and Ritson found, Urwick remained a tireless champion of Scientific Management in the face of reactions that ranged from general apathy to outright opposition.124 His behaviour with respect to his use of the military metaphor and his longstanding commitment to proselytising a military concept of organization was no different. This historical example of a failure in management theory construction and dissemination points to the importance not only of the original management thinker in the development and articulation of management ideas and concepts; but also, the critical role of the prevailing societal context. A successful imprinting of management theories upon national and international managerial practice appears more likely when there is congruence between those theories and emerging societal beliefs. 124 Ibid. 22 Estimated Annual Gross Domestic Product per Capita (Purchasing Power Parity at 1985 United States Dollar Prices ) Britain France Germany Italy Japan USA 1820 1870 1913 1950 1973 $1,405 $1,052 $937 $960 $588 $1,048 $2,610 $1,571 $1,300 $1,210 $618 $2,247 $4,024 $2,734 $2,606 $2,087 $1,114 $4,854 $5,651 $4,149 $3,339 $2,819 $1,563 $8,611 $10,063 $10,323 $10,110 $8,568 $9,237 $14,103 Table 1: Adapted from Angus Maddison, Dynamic Forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View (Oxford, 1991), 24-25. Estimated Growth of Real Gross Domestic Product per Capita (Mean Annual Compound Growth (per cent)) Britain France Germany Italy Japan USA 1820-1870 1.2 0.8 0.7 0.4 0.1 1870-1913 1.0 1.3 1.6 1.3 1.4 1913-1950 0.8 1.1 0.7 0.8 0.9 1950-1973 2.5 4.0 4.9 5.0 8.0 1.5 1.8 1.6 2.2 Table 2: Adapted from Angus Maddison, Dynamic Forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View (Oxford, 1991), 49. 23 Biographies Philip A. Ritson is a former lecturer in Management and Accounting in the School of Business at the University of Adelaide. Having taken time away from the university system to practice law, he returned to the University of Adelaide where he is currently undertaking a doctorate in the School of History and Politics on the nineteenth-century banking system in England and Wales. His publications include “Revisiting Fayol: Anticipating Contemporary Management” in the British Journal of Management, “Fads, Stereotypes and Management Gurus: Fayol and Follett Today” and “Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light: Lyndall Urwick’s Scientific Management” both in the Journal of Management History and “Accounting’s Latent Scientism: Revisiting Classical Origins’” in Abacus (all with Lee D. Parker). Lee D. Parker is a Professor in Accounting in the School of Commerce at the University of South Australia, Honorary Professor in the School of Management at the University of St Andrews and Adjunct Professor in the School of Business at the Auckland University of Technology and RMIT University. He has published over 150 articles and books on management and accounting and is a regular presenter and plenary speaker at international conferences and seminars. Amongst his recent publications are “Using Ideas to Advance Professions: Public Sector Accrual Accounting” in Financial Accountability & Management, “Building Bridges to the Future: Mapping the Territory for Developing Social and Environmental Accountability” in Social and Environmental Accountability Journal and “University Corporatisation: Driving Redefinition” in Critical Perspectives on Accounting. He is also joint founding editor of Accounting Auditing and Accountability Journal. 24