Effects of climate change on broadacre agriculture – Peter Hayman

The Carbon Farming Knowledge Project involves a series of workshops to increase the understanding of 30 independent agricultural advisers in south-east Australia on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, carbon in farming systems and the Carbon Farming Initiative – where farmers can earn credits for storing carbon or reducing greenhouse gas emissions on their properties. The project helps advisors prepare their clients for potential environmental, economic and social benefits of future carbon management policy.

Session 4: Effects of climate change on broadacre agriculture

Summary of August 2014 workshop presentation by Peter Hayman, SARDI Climate Applications Principal Scientist

Introduction

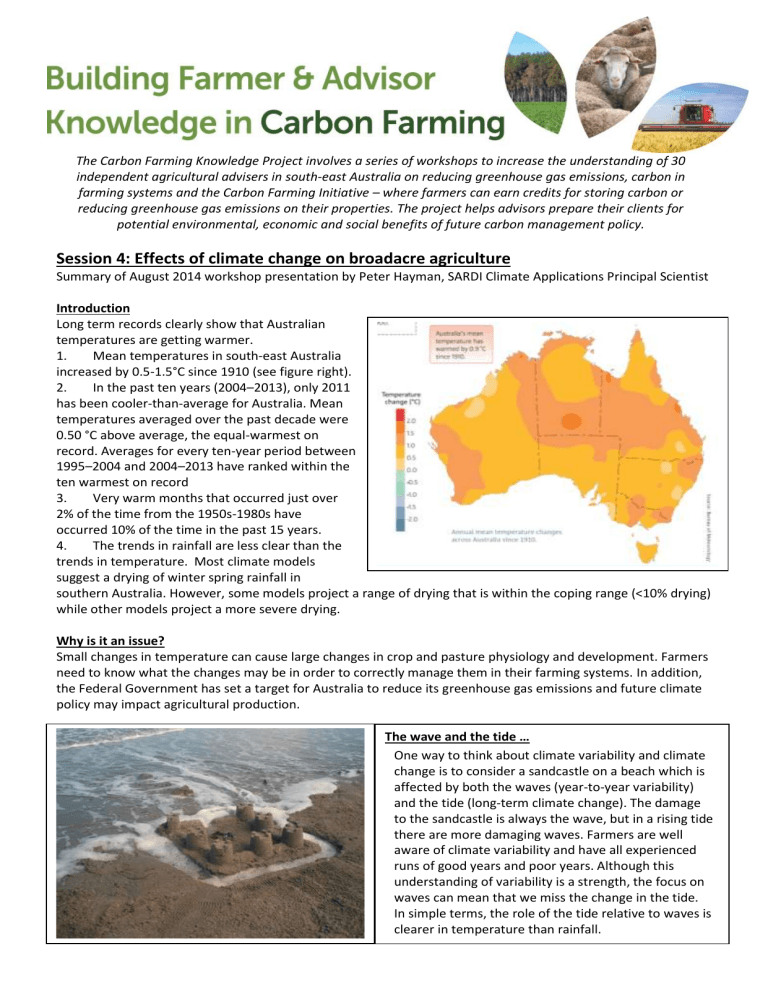

Long term records clearly show that Australian temperatures are getting warmer.

1.

Mean temperatures in south-east Australia increased by 0.5-1.5°C since 1910 (see figure right).

2.

In the past ten years (2004–2013), only 2011 has been cooler-than-average for Australia. Mean temperatures averaged over the past decade were

0.50 °C above average, the equal-warmest on record. Averages for every ten-year period between

1995–2004 and 2004–2013 have ranked within the ten warmest on record

3.

Very warm months that occurred just over

2% of the time from the 1950s-1980s have occurred 10% of the time in the past 15 years.

4.

The trends in rainfall are less clear than the trends in temperature. Most climate models suggest a drying of winter spring rainfall in southern Australia. However, some models project a range of drying that is within the coping range (<10% drying) while other models project a more severe drying.

Why is it an issue?

Small changes in temperature can cause large changes in crop and pasture physiology and development. Farmers need to know what the changes may be in order to correctly manage them in their farming systems. In addition, the Federal Government has set a target for Australia to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and future climate policy may impact agricultural production.

1.

The wave and the tide …

One way to think about climate variability and climate change is to consider a sandcastle on a beach which is affected by both the waves (year-to-year variability) and the tide (long-term climate change). The damage to the sandcastle is always the wave, but in a rising tide there are more damaging waves. Farmers are well aware of climate variability and have all experienced runs of good years and poor years. Although this understanding of variability is a strength, the focus on waves can mean that we miss the change in the tide.

In simple terms, the role of the tide relative to waves is clearer in temperature than rainfall.

Why it’s important

There is likely to be seven main changes in the climate that will affect broadacre agriculture:

Mean temperatures: Average temperatures will become warmer which means that crops will grow faster.

This is a greater problem for perennial crops in horticulture than annual grain crops. In coming decades farmers are likely to be using different varieties to target the appropriate flowering window. Warmer conditions will impact weeds, pests and diseases too, which will lead to different challenges in plant protection, depending on how they adapt.

Extreme heat: As mean temperatures increase, there is a higher chance of extreme heat events.

These spring heat evens are a greater worry than the change in mean temperature. Although the low rainfall regions are generally much warmer, the wheat crops in medium to high rainfall areas are flowering later and hence often more susceptible to heat events.

Frost risk: Although minimum temperatures are expected to increase, it is harder to be definitive about frost events. Spring frosts in the Australian grains belt are radiation frosts associated with clear night skies. If the region was to experience a drying in spring, the frequency of frost could increase. The changes in weather patterns associated with climate change may lead to more frequent inflows of dry cold polar air. Over the coming decades it is likely that untimely frosts will remain a low frequency but high consequence problem in parts of the landscape. A further complication is that the quicker development and emphasis on early planting can lead to flowering in the frost window.

Rainfall: Rainfall is the most worrying but also the most uncertain aspect of climate change for the crop livestock systems in southern Australia. Climate models suggest continued decreasing late autumn and winter rainfall across southern Australia but are unclear about trends for summer and early autumn rainfall. Soil storage of this rainfall is a clear opportunity for broadacre agriculture. A rainfall reduction of up to 10% is likely to be within the management of current farming systems. A 10-15% reduction could be challenging and lead to some significant changes in the risk profile in some farming operations. Rainfall decreases by more than 15% may require more transformational rather than adjustment changes in farm enterprises.

Rainfall intensity: Most of southern Australia has low rainfall intensity compared to northern areas. A changing climate is likely to deliver higher rainfall intensity across all of Australia, but in southern Australia this is coming from a low base. A slight increase would improve fallow efficiency and improve infiltration but a significant increase would lead to erosion.

Evaporation: As average temperatures increase, so does evaporation. There is about a 4% increase in potential evaporation per degree of warming. However potential evapotranspiration is driven by radiation, wind and relative humidity as well as temperature. Much of the change in evaporation over winter in southern

Australia will be linked to changes in rainfall. Evaporation is driven by radiation and cloud cover so a decrease in rainy days means higher potential for evaporation.

CO

2

in the atmosphere: The amount of growth per unit of water will increase with higher CO

2

levels because of improved transpiration efficiency - however scientists’ confidence is higher in the lab than the field for the observation. Weeds and pests will also benefit from higher CO

2.

Useful resources

BOM’s El Nino Watch – www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/tracker/

CSIRO Understanding Climate Change – http://www.csiro.au/Outcomes/Climate/Understanding.aspx

The Carbon Farming Initiative – www.mycfi.com.au

The Climate Institute – www.climateinstitute.org.au

Building Farmer and Advisor Knowledge in Carbon Farming Project – www.carbonfarmingknowledge.com.au

This project is supported with funding from the Australian Government

More information: Peter Hayman, 0401 996 448, peter.hayman@sa.gov.au

![1st_qtr_bulletin[1] - Nigerian Meteorological Agency](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006696528_1-5a57a09a3d4c3766eb3c736c9de82c8a-300x300.png)