bombing%20detroit-final4 - Association for the Advancement of

advertisement

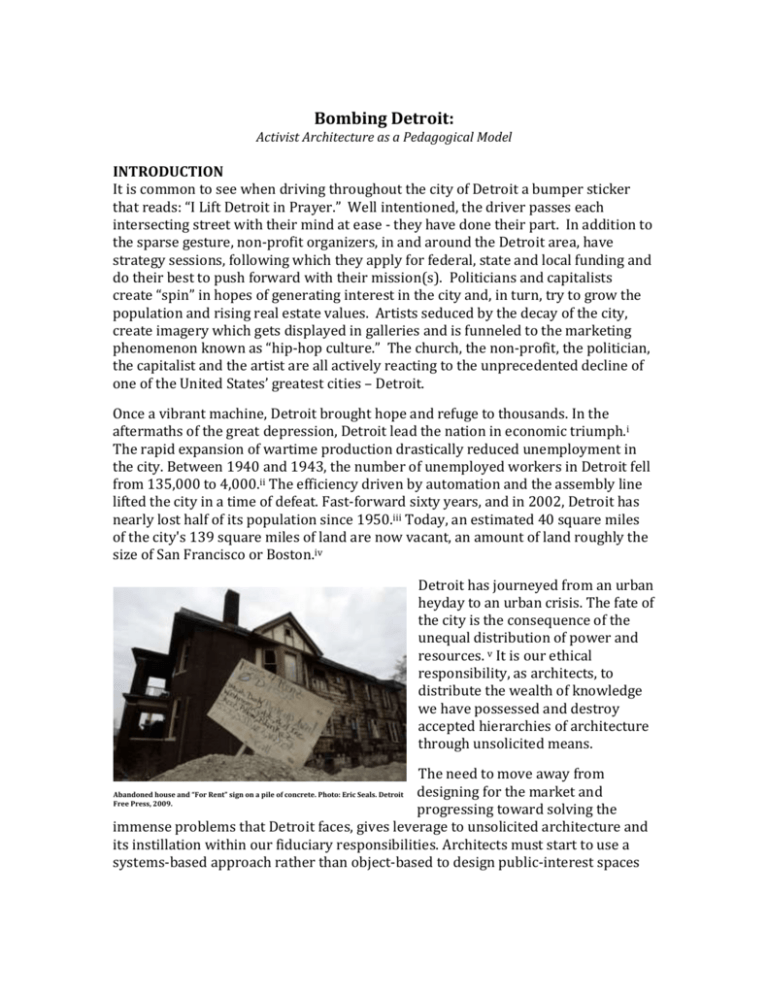

Bombing Detroit: Activist Architecture as a Pedagogical Model INTRODUCTION It is common to see when driving throughout the city of Detroit a bumper sticker that reads: “I Lift Detroit in Prayer.” Well intentioned, the driver passes each intersecting street with their mind at ease - they have done their part. In addition to the sparse gesture, non-profit organizers, in and around the Detroit area, have strategy sessions, following which they apply for federal, state and local funding and do their best to push forward with their mission(s). Politicians and capitalists create “spin” in hopes of generating interest in the city and, in turn, try to grow the population and rising real estate values. Artists seduced by the decay of the city, create imagery which gets displayed in galleries and is funneled to the marketing phenomenon known as “hip-hop culture.” The church, the non-profit, the politician, the capitalist and the artist are all actively reacting to the unprecedented decline of one of the United States’ greatest cities – Detroit. Once a vibrant machine, Detroit brought hope and refuge to thousands. In the aftermaths of the great depression, Detroit lead the nation in economic triumph.i The rapid expansion of wartime production drastically reduced unemployment in the city. Between 1940 and 1943, the number of unemployed workers in Detroit fell from 135,000 to 4,000.ii The efficiency driven by automation and the assembly line lifted the city in a time of defeat. Fast-forward sixty years, and in 2002, Detroit has nearly lost half of its population since 1950.iii Today, an estimated 40 square miles of the city's 139 square miles of land are now vacant, an amount of land roughly the size of San Francisco or Boston.iv Detroit has journeyed from an urban heyday to an urban crisis. The fate of the city is the consequence of the unequal distribution of power and resources. v It is our ethical responsibility, as architects, to distribute the wealth of knowledge we have possessed and destroy accepted hierarchies of architecture through unsolicited means. The need to move away from designing for the market and progressing toward solving the immense problems that Detroit faces, gives leverage to unsolicited architecture and its instillation within our fiduciary responsibilities. Architects must start to use a systems-based approach rather than object-based to design public-interest spaces Abandoned house and “For Rent” sign on a pile of concrete. Photo: Eric Seals. Detroit Free Press, 2009. that generate excitement and community involvement on a much larger scale, leaving no room for complacency infestation. 1. Post-industrial fiducial responsibility All architects agree to participate in ethical thought and action on many different levels. Professional Licensure, membership in the American Institute of Architects (AIA) or the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) are common ways the profession impresses upon its members a set of rules based on ethical behavior. These deontological forms of ethics attempt to promote good character and behavior. Neglected in each one of the organizations listed above is the proactive, ethical behavior expected from professionals in a time of crisis. This is not to imply that law, or professional organizations should obligate architects to fix societal issues, rather a suggestion to re-examine the ethical behavior of complacency. The current state of Detroit exposes how unacceptable it is for such an empowering and encompassing profession to let its standards fall short of success. Many well-intentioned architects have become involved in a contagious reaction to Detroit’s destruction. Countless conceptual projects have been completed on how to “re-build” the city of Detroit, on a professional and academic level. Regional architecture schools of Detroit have a hard time getting through a semester without having a studio get involved with a Detroit related “issue.” Innovative new models of practice have evolved which focus on displaying the untapped talent of the city. Outside of these new models and other valuable examples, the majority of local and national architects keep a safe distance due to the lack of funding and development. It is fair to say that design alone cannot fix Detroit. It is also important to note that architects should be cautious not to operate within the idea of a design utopia. Despite the economic, professional and philosophical challenges, architects cannot negate their responsibility to Detroit. A new model of architectural practice must be sought to allow further fulfillment of a post-industrial fiducial responsibility. The current ethics that we operate under need to be expanded to address the context of practice in Detroit. Post-industrial fiducial responsibility requires: 1. Pro-active community engagement 2. Design solutions regardless of economic return 3. Complacency is an act of malpractice To accept this expansion of ethical behavior is to stand for a subversive architecture of our time. A deconstructive thought, in regards to creating spaces, facilitates infinite subjectivity and fulfillment. The installation of a client[less] architecture, proactive and unsolicited, is crucial to the survival of Detroit (and many other perishing cities, alike). Deconstruction, rather than a negative process of dismantling, is affirmative because it frees concepts from their historical foundations and opens up new possibility. Architect and author Mark Wigley says it’s simply, “the ability to disturb our thinking about form” that makes a project deconstructive.vi 2. Bombing and Getting Up In the study of alternative models of practice we must look outside of the profession. The success and bravado of the graffiti or street art movement grew out of America’s ghettos. “Tagging” possesses a systematic model of practice that cannot go unnoticed, in relation to architectural practice. The “writers” and their art have proven to be one of the most successful campaigns to modify the urban landscape. Unfunded and unsolicited, tagging began as an activist response to the flaws of modernism. Modernism became the force that drove the development of our postwar cities giving leverage to writers to use bombing as a tool to change shared expectations of how, where and why we communicate. There was a growing rift between rich and poor and urban and suburban.vii Angry youth of the 1970’s reacted with the most common weapon – words and language. Unwittingly, the writers (as they like to be called) visually deconstructed modernism and the technological utopia that promised better living for all. It is simple for the academic, political and societal community to dismiss these artists as vandals; pariahs on society that destroy, not build communities. Graffiti is only dangerous in the mind of three types of people; politicians, advertising executives and graffiti writers.viii There are valid reasons for the antagonists’ argument, but deeper analysis of bombing is being sought. Why do the writers write? What are the systems at work that will provide valuable insight for architects working in an economy with little to no financial or governmental support? Taki 183 was a teenage foot messenger in New York City in the early 1970’s. Taki 183 spread his infamous “tag” or street name throughout the city.ix This practice of tagging repeatedly or “bombing” was copied repeatedly throughout New York and the world. The system of gaining notoriety or “getting up” became a badge of honor and rank within the community. The system was set in-place primarily as a campaign or protest of teenage angst. Street artists were reacting to what they felt were unacceptable conditions. Many years later in the early 1990’s a curious sticker started appearing on the east coast of the United States. Stating simply, “Andre the Giant has a Posse.” Using the face of the iconic oversized wrestler, the artist Shepard Fairey, then an art student at the Rhode Island School of Design, created a street art project rooted in phenomenology.x The ambiguous sticker and its persistence in the environment jolted the public’s curiosity and forced them to consider both the sticker’s message and its relationship to the environment. Taki 183, Photo: Don Hogan Charles, New York Times. 1971. Shepard Fairey’s sticker campaign has evolved into a simplified version of Andre with the words OBEY; Fairey’s public comment on our tendency to follow the herd. Both Taki 183 and Fairey’s work is subversive and at times destructive. However, the success of these “campaigns” and their ability to use their art and designs as a tool for activism is relevant to community architects practicing in Detroit. Bombing has established itself as an independent discipline that understands how to manage and employ meaning within a cultural context by way of systems based thought.xi Obtaining a noncomplacent and activist stance, large amounts of tagging and bombing may just prove to obtain a high level of city pride. A city’s lack in the activist communication, to me, is just complacent. The activist and in-your-face tactic associated with graffiti has allowed the system-based approach to be heard loud and clear and followed across the world. Sticker, Shepard Fairey. 1989. As Klaus Krippendorff describes in The Semantic Turn, aesthetic, and market considerations that justified products of design in the past have been replaced or overshadowed by more social, political cultural and ecological concerns.xii The ideal of single-genius and single-solution architecture must remain in the past for community architecture to succeed. Striving to be the single genius with “the answer” is hindering the insurmountable possibilities of society-based architecture. J. M Carroll notes that a preferred mode of design is an approach ‘predicated on the concept that people who ultimately use a designed artifact are entitled to have a voice in determining how that artifact is designed’. xiii As unsolicited architects, we can learn by way of precedent graffiti artists to create an unambiguous model for actively pursuant, public-interest and Client[less] architecture leading the pack subversively, instead of following the herd ineffectively. By doing so, Detroit may have the opportunity to “get up” and earn its badge of honor that has been long lost. 3. Client[less] Praxis The architectural profession has become inseparable with the client. The “client” has evolved to the singularity of the individual or institution that seeks our advice and is willing to pay the market rate. This model of practice limits architectural impact on our society and in particular to the city of Detroit. The people we serve, as a profession is limited to architects only creating 2 to 5 percent of our built environment.xiv As architects, we allow clients to determine our agenda. xv Architecture has become a form of oppression by only allowing those with adequate funding to prosper from professional design. Our own standard model of practice, and the economic returns we expect, is in direct conflict with our fiduciary responsibility to the health and welfare of our community. It is the architect’s responsibility to invent new ways of working in the post-industrial landscape and to stop wondering where we can find clients and start asking where we are needed.xvi Action is required in Detroit. The obvious answer is to be involved in a community architecture firm that focuses on projects that are in favor of the public-interest. The organizational structure of most community architecture firms is a modification of the standard model of practice. Most community architecture firms are still organized to address the four pillars of architecture: client, site, budget and program. Even if a public-interest firm is successful by utilizing the standard model of practice their impact will be minimized due to limited funding, clientele and time. Currently, a designer willing to be involved will find few financial resources to implement ideas and designs. To stand idle for a top-down solution to arrive only extends the architect’s failures. A bottom-up approach must be explored to free our concepts from historic foundations and open up new possibilities.xvii Ole Bouman of the Office of Unsolicited Architecture (OUA) suggests dismantling the four pillars of architecture thereby creating a new autonomy for architecture.xviii Bouman’s assertion provides a possible roadmap for architects dealing with what, at times, seems insurmountable. In particular, one strategy found in this proposal is the removal of a client or providing unsolicited architectural services. This client[less] mode of practice should not be seen as self serving, although it can be, rather unrestricted. The removal of the singular-client, single-solution role, changes the focus of our profession to the community and away from the elite few and away from the single aesthetic solution to an integrated systems based approach. The client becomes the community, the community does not commission, but receives solutions; solutions that otherwise would not be funded by private developers. Operating client[less] allows the Detroit architect to provide inventive design solutions to an unlimited number of people. Yes, client[less] solutions are modest, but the intent and proactive nature in which it is carried out is significant. Bouman’s guidelines for adaptation of architectural praxis instruct practitioners to take a multi-step process to insure they are making “unsolicited architecture”. A checklist including: defining new territory, transgression of the 4 pillars of architecture, design, reflection and action outline the primary elements of his process. Although the process is proactive and unsolicited it is important to note that the guidelines do not insure outcomes or motivations or that the project will be in the public interest. “Courage demands leaving the safe and trusted logic of the assignment behind in order to tread the field of venture development,” (Arjen Oosterman, Volume 14). It is our fiduciary responsibility as architects to stop acting like proprietary investors and start building the existing model with a systems-based, moving forward approach. Like the writers of graffiti, leave your inhibitions at the door and actively participate independently in a subversive, persistent and contagious phenomenon. Instill your own permission to design non-mediocre and uncontrollable systems for the betterment of a community in dire need of smart, architectural space re-configuration. There are always two outcomes: either the community will react (positive outcome) or the community will sit still (negative outcome). Either way, the notion of empowerment will be instilled and the system you create will set a standard for future expansion. 4. Activist Design and Sustainability Embedded in both clientless and unsolicited modes of design is an underlying thread of activism, in which the designer – with or without a specific user in mind – undertakes a critical assessment of a given condition, and attempts to enact change toward a more equitable and acceptable paradigm. Alastair Fuad-Luke provides the following definition: Design activism is design thinking, imagination, and practice applied knowingly or unknowingly to create a counter-narrative aimed at generating and balancing positive social, institutional, environmental and/or economic change. xix Activist architecture necessitates an entirely new skill set. Whereas schools of architecture pride themselves on educating their students to be ‘problem solvers’, designers educated through a pedagogy of activism and seek to be ‘problem seekers’. In addition, activist architecture prohibits neutrality, as the designer must fully embrace societal needs and advocate for change. Precedents for activist architecture abound, and often have grown out of ‘guerrilla design’ activities. One such example is the work of Mad Housers, founded by Georgia Tech graduate students Michael Connor and Brian Finkle in 1987. In an attempt to address the issue of homelessness in Atlanta, the strategy of the Mad Housers was to construct make-shift shelters, and deliver them by night to underutilized properties, where they were ‘claimed’ by members of the homeless populace. Today, the Mad Housers are a registered non-profit organization, which builds ‘huts’ for specific clients, many of whom participate in construction. The transition from ‘guerilla activists’ to ‘legitimate’ service providers underscores the opportunities for architects to fulfill their fiduciary responsibility within a matrix of social and professional sanction. Numerous prominent activism-based design initiatives have come to flower, including Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio at Auburn University, Public Architecture, and Architecture for Humanity. The connection between activist architecture and sustainability may not seem apparent to those who narrowly define sustainability as the integration of living roofs and alternative energy sources into works of architecture, but becomes readily apparent on two points when one is inclined to look below the surface. On the first point, the humanist core of activist engagement addresses one of the legs of the ‘triple bottom line’ (ecology, economy, equity) often left out of traditional pedagogy. While it is a relatively simple matter to educated architecture students on the environmental impact of their designs, and the resulting economic impacts of certain design decisions, defining and promoting the architect’s role as an advocate of social equity remains more elusive. In many cases, focus upon equity has become the province of design for the ‘have not’s’. Explained simply, the concept of ‘environmental justice’ can be viewed as follows: using innovative design solutions to save a software CEO ten dollars a month on his utility bill is an insignificant exercise, whereas a ten dollar monthly savings to the resident of subsidized housing may make the difference in the decision to keep the lights on or buy food. Secondly, the very act of sustainable design implies advocacy on behalf of a client who remains (aside from floods and landslides) a primarily silent one: the environment itself. The architect who dedicates herself to sustainable paradigms must stand firm in advocating design decisions in which immediate financial profit may not be her highest priority. Even within the sometimes-accepted paradigm of ‘climates before primates’, environmentally-conscious design efforts yield the (occasionally unintended) result of relieving some of the industrialized damage inflicted upon low-income communities. 5. Activist Pedagogy In an effort to engage students with the community as activist architects, two graduate levelcourses are offered in the sustainability concentration at Lawrence Techonlogical University. The Graduate Design Studio: Massive Change, challenges students to view their community with critical eye, and to propose design solutions to enact change within their local contexts. Students are first given an assignment entitled ‘Picture the Problem’ (taken from educational materials provided by the Institute Without Boundaries) in which they are charged with identifying unsatisfactory conditions within the current context. The students are then required to engage representatives of the community, and propose design solutions. The design solutions are aimed to help mitigate the sometimes-oppressive conditions from which the stated problem has sprung. Resulting studio projects have vary in scale and complexity from street-vending carts to small-scale urban plans. The seminar titled “Architecture as Activism” is centered on a client[less] project in Detroit. The project was predicated on the idea that architecture can be an act of intervention; to intervene or mediate a dispute is a powerful act of design. Each student is engaged within the city of Detroit, and identifies a situation that is continually ignored; one that incites protest and activism. The students “protests” manifested through design solutions are then built and implemented on-site. Design considerations are given to the size and scope of each project insuring completion within the time allotted. The students are encouraged to be subversive and independent but instructed not to be vandalistic. The projects outlined in these courses prove to be a formable challenge. The students have to independently identify Bouman’s “new territory.” To do so, time and contemplation is required within the community. The “client” for many of the projects are the community itself, which is disorienting to the students since the normal practice within studios labels an individual or company as a client. A systems-based approach must affect a community entirely instead of an individual and help facilitate the health, safety and welfare of everyone. For Bouman’s system to work in Detroit and to insure that it worked in the public’s interest the Client[less] checklist has been modified to the following: Client[less] in Detroit Checklist 1. Identify an urban condition that incites protest and activism (new territory). 2. Insure the issue is unnoticed, neglected or client[less]. 3. State the outcome of the project and the social impact(s) it will have on the community. Insure that the project is socially important and not simply a self-validating embellishment of the city. 4. Provide a full scope of architectural services. Although the project is client[less] it does not negate professionalism. 5. Reflect on the selected territory the design solutions and the potential outcomes. Operating client[less] requires architects to become their own best critics. 6. Implement independently and subversively. 6. The Barbara Rennie House Already a seasoned activist in the city of Detroit, student Jason Fligger had previously participated in urban farm initiatives, and supervised a barn-raising by the students of Detroit’s Catherine Ferguson Academy. When he undertook this project, he began by uncovering some disturbing truths about the plight of unwed teenage mothers in the city. Jason’s research uncovered that only one Metro Detroit shelter provided emergency services to teen mothers. Typically, a young woman who found herself temporarily homeless became engaged in a maddening merry-goround with Social Services, which usually resulted in the separation of mother and child to separate foster facilities. Furthermore, Jason identified the fact that many of these women found themselves in an endless cycle of poverty, as the burdens of motherhood often forced them to abandon their dreams of completing their education and provide better lives for themselves and their children. Engaging six students from Catherine Ferguson Academy (all teenage mothers), Jason embarked on a two-pronged project, treating these women as his clients, his partners, and his students. In structured sessions, Jason worked in partnership with these women to develop the program, select the site, and develop design ideas for the Barbara Rennie House. The proposed project would provide emergency shelter for homeless teenage mothers, including space for a resident ‘house mother’ (thereby providing an onsite foster authority for mothers and their children), on site security, children’s activity areas, and study space to promote harmony between mothering and education. The proposed building featured a number of sustainable features, including brownfield redevelopment, SIPS construction, daylighting, natural ventilation, stormwater management, solar hot water, and a hydronic heating system. The major efforts regarding sustainability, however, were not focused upon the design of the building, but rather upon the growth of the students themselves. Acting in a mentoring role, Jason took the students on tours throughout the city, introducing them to the rich architectural history of Detroit. In addition, through working sessions developing the Barbara Rennie House proposal, students were engaged as active participants, identifying needs and co-generating concepts. The end result was to activate an interest in design as a potential career, and to promote self-awareness that their ideas and concerns were indeed formidable. By exercising their ‘voice’ in the design process, Jason’s intent was to encourage them to believe more strongly in their intellectual and creative abilities, and to shift their focus from consumptive to productive activities. In this project, Jason embodied true sustainability through one of Fuad-Luke’s tenants of participatory design: ‘building capacity, not dependency – by not only shaping a solution but leaving behind the tools, skills and capacity for ongoing change’.xx 7. Seed Detroit The students needed to look beyond the urban decay for the less obvious, the potential of place and the dynamic social variables. One of the activist projects manifested as Seed Detroit - a significant virtual and physical system in the devastated Brush Park neighborhood of Detroit. Seed Detroit became the project but also the tag of student Emilie Naismith. Remaining anonymous, the student developed www.seeddetroit.blogspot.com thereby withholding identity to keep the focus on the seed bombing campaign. For the intent of the design to be valid the designer had to be rigorous to insure that this was not simple voyeuristic aestheticism. xxi Designers gawking and providing clever instillations that are not in the public interest is nothing new in Detroit. Inspiration for Seed Detroit came from the notion that beauty can come from decay. From 1950 to 2000 the population of Detroit deflated from 1.8 million to just over 951 thousand. The construction industry followed suite and from 1978 to 1998 only 9,000 building permits were issued while 108,000 demolition permits were issued.xxii The result was the development of an urban prairie that creates a quiltlike pattern divided by Detroit’s nonindulgent grid. The prairie grass grows tall, overtaking the remnants of the buildings that once stood. On the quiet streets of Detroit, one can walk among these reconstituted prairies and experience a unique un-urban environment. The question that arose during Emilie’s project became, how can we as community architects make the remaining residents realize this beauty, how can we subversively assist in success? First, Seed Detroit built awareness and notoriety through a sticker and web campaign - getting up. The bright yellow graphic with opposing flowers and Detroit skyline resonated with the residents of Brush Park. Followers of the blog began to make a connection between the sticker and the seditious, yet pastoral sign of the same graphic that was erected on a central Brush Park lot. The design called for seed containers to be propagated throughout the neighborhood. Each container (or envelope) contained native wildflower seeds to be spread in the prairie by one person totalling 19 square feet. The containers were located on metal municipal signposts surrounding the grids of prairie land. A passerby would take the container, spread the seeds, and return the container (or not). As a reward for participating, the spreader or “agent” received a Seed Detroit sticker and an “agent number.” The “agent” was instructed to report back to Seed Detroit with the spread location for mapping studies, determining future seed bomb locations. Seed Detroit Sticker, Seed Detroit, 2009. Seed Detroit Flyer 1, Seed Detroit, 2009. The result was the propagation of wildflowers over the Brush Park Neighborhood. The design is significant because it was implemented without a client and without any significant funding. The design is a system, not a building; providing agents (citizens) to interact with the built environment and to make independent modest improvements that evoke a sense of advancement. The project not only engaged students into Detroit it also put in place a positive, client[less] system that carried on beyond the classroom. The designer did not set out to create a single built solution but phenomenological system to enable and improve Brush Park, unsolicited. Seed Detroit Flyer 2, Seed Detroit, 2009. Seed Detroit Installation, Seed Detroit, 2009. Seed Detroit Blog Post, Seed Detroit, 2009. CONCLUSION A revival of the architect’s attributed role is in order. We must start to organize space as we have always done, but now, more than ever, we need to organize systems intelligently, unsolicited, and clientless. A new subjective approach to design, rather than an objective approach, will expand public-interest architecture and exercise the possibilities of our fiduciary responsibility. An object-based approach is hindering with regard to the types and amounts of architecture and available funding. A systems-based approach, not unlike the systems utilized throughout the graffiti nation need to be adapted to advance the profession in the declining and deprived city of Detroit. Architecture as art, science, innovation, ideal, adventure, aid and rescue always relies on self-motivation, curiosity, a sense of urgency and an antenna for opportunities.xxiii To solely practice complacent architecture is a waste of an education and certification. The industry must explore the design possibilities of unsolicited architecture to fulfill our ethical role within the community. The city of Detroit is perishing and has been for some time. Now is the time to deconstruct the accepted hierarchies of architecture and build expectations of the profession from the bottom-up. A societal gathering of ideas and inspiration will produce further advancement in the re-creation of Detroit. Proactive solutions to neglected spaces will reap larger benefits than any funded building. Complacency ends with activist architecture. The intended result of the courses discussed above is to empower a new generation of architects to respect their post-industrial fiduciary responsibility and question the traditional paradigms of practice – to share in Cameron Sinclair’s vision that ‘for every “celebrity architect”, there are hundreds of designers around the world, working under the ideal that it is not just how we build but what we build that truly matters.xxiv To say that architecture, like graffiti, has a limit to its effectiveness should alone be enough to draw an up-rise in the profession to deconstruct the notion of clientpractice, push boundaries and create social-architecture that has no limit. A systems-based approach will spark an architecture intervention with decisive concepts and powerful scenarios that will shift Detroit’s deadlocked discourse into a, once again, thriving, protagonist city.xxv Sugrue, Thomas J. Origins of the urban crisis race and inequality in postwar Detroit : with a new preface by the author. (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2005) Print, 19. ii Sugrue, 19. iii Sugrue, XVI. iv Gallagher, John, “Detroit’s fight against vacant land gets tougher,” Detroit Free Press, September 29, 2009, Real Estate section. v Sugrue, pg 14. vi Amos Klausner, “Bombing Modernism: Graffiti and its relationship to the (built) Environment,” vii Klausner, 8. viii Banksy. Wall and Piece. (New York: Random House UK, 2007) Print, 8. ix 'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals, New York Times (1857-Current file); Jul 21, 1971; ProQuest Historical Newspapers, The New York Times x Fairey, Shepard. OBEY, Supply and Demand, The Art of Shepard Fairey. (Gingko Press, 2009). Print. xi Klausner, 8. xii Adhya, Anirban, Philip Plowright and Jim Stevens. “ Rethinking models of architectural research: we don’t do objects.” Paper presented at the ARCC 2009 Leadership in Architectural Research Conference, San Antonio, TX, April 15-18 2009. xiii Carroll, J.M (2006) ‘Dimensions of Participation in Simon’s Design’, Design Issues, vol 22, no 2, pp 3-18. i Bell, Bryan and Katie Wakeford. Expanding Architecture, Design as Activism, 2008, Metropolis Books, 9. xiv OUA. Volume 14-Unsolicited Architecture. Vol. 14. (The Netherlands: Stitchting Archis, 2007). Print, 31. xvi Volume 14, 28. xvii Klausner, 8. xviii Volume 14, 31 xix Fuad-Luke, Alastair (2009) Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World Earthscan London p. 26 xv xx d. Fuad-Luke, p 150. Daskalakis, Georgia. Waldheim, Charles. Young, Jason: Stalking Detroit. (ACTAR, 2001), 33 xxii Stalking Detroit, 33 xxiii Volume 14, 28. xxiv Sinclair, Cameron (2006) Design Like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises. Metropolis Books, New York. P. 31. xxv Volume 14, 28. xxi