Jones Act

advertisement

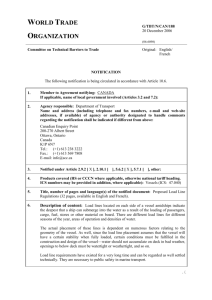

What is the Jones Act? The Jones Act is the everyday name for Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (46 U.S.C. 883; 19 CFR 4.80 and 4.80b). Its intent is very simple — to promote a healthy U.S-Flag fleet and protect that fleet from unfair foreign competition, the Jones Act requires that cargo moving between U.S. ports be carried in a vessel that was built in the United States and is owned (at least 75 percent) by American citizens or corporations. Since Jones Act vessels are registered in the United States, our general labor and immigration laws require that crewmembers be American citizens or legal aliens. Was the Jones Act pioneering legislation? Quite the contrary. The U.S. government has had “Cabotage” laws since 1789. The Jones Act merely recodified existing statutes. Is the Jones Act uniquely American or do other nations have similar laws? The concept of Cabotage is common to virtually all nations with a Merchant Marine. Nearly 50 countries throughout the world have laws similar to the Jones Act. What about America’s neighbors, Canada and Mexico. Both Canada and Mexico share the U.S. requirement that the ship (or tug/barge) is owned and crewed by nationals. Neither nation prohibits importation of a vessel, but in the case of Canada, a foreign-built ship cannot enter the coastwise trades until its owner has paid a tariff equal to 25 percent of the vessel’s value. As a result of this tariff, very few Canadian lakers are foreign-built. Does the Jones Act apply to passengers? The Act, no; the principle, yes. What is known as the Passenger Vessel Act of 1886 (46 U.S.C. 289) states that “no foreign vessel shall transport passengers between ports or places in the United States, under penalty of $200 for each passenger so transported or landed.” How do the requirements of the Jones Act compare to the rules applied to other modes of transportation in the United States? American railroads, airlines, truck lines, busl ines... operate under virtually the same rules. Although the percentage of ownership that can be foreign varies from mode to mode, land and air must be U.S. corporations, at least in terms of the operating entity, and employ American citizens (or legal aliens). What is different is that American ship owners must buy and maintain their vessels in American shipyards. This “Buy American” provision sounds anti-competitive. Wouldn’t American ship owners benefit from being able to shop the world for their ships? If one can guarantee that American troops will never again fight on foreign soil and/or that foreign governments will end their massive subsidies to domestic shipyards, then the Build American requirement could be retired. Given a level playing field, American shipyards can compete. However, you must remember that America is an island nation and needs a shipbuilding industry to build and maintain the vessels needed to supply those troops. The shipbuilding industry worldwide is so rife with trade-distorting practices that for the sake of national security, American shipyards need the protection of the Jones Act. Can the Jones Act be suspended or waived? Yes, but only during a national emergency. During World War Two and the Korean Conflict, Canadian lakers were allowed to carry iron ore and grain between U.S. ports. Today, if there is an energy emergency, the Administration can allow a foreign-flagged vessel to carry energy products between U.S. ports. Also, certain foreign-owned companies can operate a U.S.-Flag ship or tug/barge in the Jones Act trades provided the vessel only carries raw materials as a service for a parent or subsidiary corporation. Do Jones Act carriers receive any government subsidies? Absolutely NOT! Congress has expressly prohibited Jones Act carriers from participating in the various Operating Differential Subsidy (ODS) or Construction Differential Subsidy (CDS) programs enacted over the years to promote a U.S.-Flag ocean-going fleet in the foreign trades. (These subsidies are sadly necessary for deep sea carriers because they must compete with substandard ships and operators, some using ships built with foreign government subsidies.) The only assistance occasionally available to Jones Act carriers is a government guarantee of the ship’s mortgage. No U.S.-Flag operator of self-propelled vessels on the Great Lakes has ever defaulted or even missed a mortgage payment. How has the Jones Act benefited Great Lakes shipping? The Great Lakes are the safest and most efficient waterway in the United States (in fact, the world) for the simple reason that U.S.-Flag carriers have been provided a level playing field and thus been able to invest in the most technologically advanced vessels in the world. So efficient are Great Lakes vessels that a 1,000-foot-long self-unloader historically has carried 65,000 tons of iron ore the 800 miles from Lake Superior to Lake Erie for roughly $6 a ton. Freight rates for short-haul cargos are as low as $2 a ton. In terms of real dollars, 1995 freight rates are below those charged five years ago. In some trades, freight rates in recent years were virtually the same as the early 1980s. The Great Lakes are the source of drinking water for 25 million North Americans. Recreational boating and commercial fishing are important industries in the Great Lakes region. Does the Jones Act provide any environmental protections that would be absent if the law was repealed? Quite definitely! Jones Act vessels are built and operated to the world’s highest Safety standards. All Safety-sensitive functions on self-propelled vessels are performed by crewmembers licensed or documented by the United States Coast Guard. To receive a Coast Guard license or qualified rating requires the mariner to pass extensive examinations that attest to his/her skills and knowledge. We’re not trying to scare people. Many foreign-flag vessel operators are reputable and employ qualified crews. Nonetheless, it is a F A C T that the ocean-going maritime industry is plagued by substandard ships and crews. Every day Port State inspectors throughout the world detain ships because of serious safety violations. To our knowledge, no U.S.-Flag vessel in either the domestic or international trades has been detained. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), an agency of the United Nations, is trying to raise worldwide standards for ship operation, construction and manning, but has a long way to go. Do Jones Act carriers have any competition? Absolutely! Carriers compete fiercely among themselves. The days of the long-term haulage contract are largely a thing of the past, so it is common that the ABC Steel Company will give its float to Fleet A this year, Fleet B next year... Rates are so competitive that contracts can be lost on tenths of a cent per ton. Jones Act vessels also compete head-on with the very efficient longhaul railroads and, in certain trades, trucks. Why do U.S.-Flag operators charge more than foreign-flag shipowners? U.S.-Flag freight rates are higher because American steamship companies pay taxes to the Federal, State and local treasuries... because American mariners earn a wage commensurate with the American standard of living and the transportation field... because U.S.-Flag vessel operators comply with U.S. Coast Guard regulations, American labor laws, safe workplace laws... There are few products or services made or provided in this country that couldn’t be done cheaper if foreign labor or raw materials were used, if the company could avoid taxes and regulations... To label U.S.-Flag vessel operators “high-priced” is a deliberate distortion. As a result of direct foreign competition, many American companies have undergone painful restructuring. How have Jones Act carriers on the Lakes responded to changing economic times? Great Lakes shipping did not go unscathed during the recession of the early- and mid-1980s. Approximately 60 ships were scrapped as the industry downsized following the massive reduction in steelmaking capacity. (In mid-1970s, the American steel industry had an annual capacity of 160 million tons. At one point in the recession, capacity had fallen as low as 112 million tons.) Two major fleets exited the business completely. The carriers that survived the recession did so by aggressive cost cutting. Employees made sacrifices. Crew size averaged 32 or more before the recession. Today a laker carries a crew of 27. Salaries and benefits were reduced or frozen, and although labor and management are united in their support of the Jones Act, they know they face more difficult decisions about crew size and work rules in the future. American Great Lakes ports now rarely ship government-impelled agricultural cargos (PL480). What role has the Jones Act had in this development? None whatsoever. The U.S.-Flag requirement for government-impelled cargos is separate legislation. Furthermore, since there are so few U.S.-Flag ocean-going liners small enough to transit the St. Lawrence Seaway, Great Lakes Jones Act operators and other maritime interests have agreed to a complete waiver of the U.S.-Flag requirement in the hopes that U.S. Great Lakes ports will regain a share of this trade. However, even with this waiver, it will be difficult for Great Lakes ports to re-enter this trade. The Lakes international trade is hampered by the seasonal closing of the Seaway. The ports on the Coasts ship year-round. Coastal ports load 105- foot-wide ships to drafts of 35-45 feet. The locks in the St. Lawrence Seaway and Welland Canal limit the international trade to ships no wider than 78 feet and drawing no more than 26’ 03.” A Jones Act opponent contends that with an average age of 37 years, the Lakes Jones Act fleet is old and inefficient? 37 years does seem like a long time for a ship to be in operation. For most segments of the maritime industry, a 37-year-old ship is indeed a veteran, ready for retirement. Ships that operate in salt water generally have productive lifespans of 20 years or so. However, since Great Lakes vessels spend their entire life in fresh water (sweet water in maritime lingo), a properly maintained hull has an indefinite lifespan. That’s why most of the lakers built in the 1950s are still in service. However, compare a photo of say the PHILIP R. CLARKE when she was christened in 1952 and today and you won’t know you’re looking at the same ship. Since being launched, the ship has been lengthened and converted to a self-unloader. Remember too that when we refer to a vessel’s age, we are talking solely about the hull. Internally, U.S.-Flag lakers boast the most modern navigation and operating systems known to the maritime industry. One frequently voiced criticism of the Jones Act is that the law has hindered the movement of grain from Great Lakes ports to East Coast destinations, specifically, North Carolina. Is this true? Glance at a map of the country and the answer to that question becomes obvious to even those unfamiliar with the transportation mode. To move grain from the Lakes to North Carolina would require the shipper to hire the vessel for 18 shipdays. (Shipdays include loading and discharging in addition to the actual transit.) A unit train could accomplish the task in 2 days at most. Even a “bargain basement” third-flag vessel with the cheapest third world crew could offer a better rate than the railroads only under most ideal circumstances. Furthermore, there are no grain elevators at North Carolina ports. The Jones Act Reform Coalition states that “no Jones Act-qualified vessels are available for transportation of American-produced salt from one U.S. Great Lakes port to another;” that U.S.-Flag Great Lakes carriers “simply are not interested in transporting this commodity.” Is there any validity to this statement? Virtually none! During the period 1995-1989, the members of Lake Carriers’ Association carried 5,489,174 tons of salt, most of which moved in the Jones Act trades. A major player in the domestic salt trade is not a member of LCA, thus does not participate in our cargo survey. The actual total is significantly higher than 5.5 million. It is true that many shipowners have serious reservations about carrying salt. Salt is an extremely corrosive cargo. Anyone who drives a car on salted roads in the winter knows what damage salt does to metal. The damage is even worse when concentrated in a ship; the salt gets into the machinery and hull structure. A ship could be retrofitted to carry salt without major damage to the vessel, but such an investment would require a long-term haulage contract, a thing of the past in the entire U.S. transportation industry. Some salt suppliers have considered owning their own barges and ships, but do not want to risk their own investment. Jones Act critics say the Cabotage laws have failed to achieve their goal and point out that the U.S.-Flag fleet has declined from 2,500 ships in 1945 to 354 today. How do you respond? This criticism is wrong on two points. First, that 2,500 ship fleet included the deep sea armada that had swollen to meet the needs of World War Two. It was natural that the U.S.-Flag fleet would return to pre-war levels after hostilities ended. Secondly, the reduction in the number of ships reflects the tremendous increase in individual vessel carrying capacity. The 620-foot-long lakers built during World War Two carried 15,000 tons per trip on a good day and were in service from early April until late December. Modern-day lakers routinely carry anywhere from 30,000 to 70,000 tons per trip and operate from late March until mid-January or later. Concerning the decline of Jones Act vessels in the coastal trades, remember too that in 1945 the United States did not have the interstate highway system. Unit trains, double-stack container trains, pipelines, “just in time delivery”... all these developments produced a modal shift. The cargos that once moved on the Coasts in U.S.-Flag vessels are now carried by American railroads and trucklines employing American citizens. Canada is one of the United States’ closest friends and its maritime laws and regulations often mirror their U.S. counterpart. Why would it be unfair to allow Canadian lakers into our domestic trades? It’s quite true that Canadian lakers are built and operated to Safety and Environmental standards that closely correspond to U.S. laws and regulations. The Canadian ensign is by no means a “flag of convenience.” However, different governmental approaches to the maritime industry, both historically and today, would create an unlevel playing field were Canadian-flagged ships allowed into our domestic trades. Until the mid 1980s, the Canadian government heavily subsidized construction costs for ships built in Canada. U.S.-Flag Great Lakes operators were never allowed to participate in the Construction Differential Subsidy Program (now defunct). The comparative lack of debt service would allow Canadian operators to unfairly underbid U.S.Flag carriers. Furthermore, there are vast differences in the taxation and social benefit policies affecting U.S and Canadian carriers. Simply put, Canadian carriers would have advantages that stem from government policy, not entrepeneurship. Does the Jones Act need any changes? No. The Jones Act as maritime policy is an appropriate national policy for the United States, the last superpower in the world. If you mean do we change in the regulatory environment in which Jones Act carriers operate, the answer is, of course, Yes. The rules and regulations applied to U.S.-Flag vessels must constantly change with the times and reflect advanced technology. To the degree that Safety permits, the regulatory environment must recognize the competitive pressures facing carriers and their customers. We must not forget as Americans with a higher standard of living than the Third World countries which supply mariners to most ocean-going ships that the higher costs associated with the U.S.-Flag registry are not caused by the Jones Act, but by doing business as American corporations in America. What would be the aftermath of repealing the Jones Act? First, Great Lakes shipping would degenerate into a constant succession of flag of convenience operators. In would come one registry, only to be replaced by another with even less regulation and oversight as customers competitively seek the lowest-cost operator. There would be absolutely no stability in the marketplace. In times of war or a national emergency, there could be no shipping whatsoever on the Lakes. The foreign-owned and crewed ships could be ordered by their government to not serve the U.S. trades. This may sound far-fetched, but do not be lulled into a false sense of security by the Persian Gulf War. That situation was unique in that virtually the whole world was united in its condemnation of Iraq. Such unanimity is unlikely to happen again. During the Six Day Israel-Egypt War in 1967, The Arab League boycotted any country which provided arms to Israel and refused to allow any American-Flag ship which called at an Israeli port to trade with an Arab League country. Even our closest allies do not always share our goals and objectives. France refused to allow U.S. bombers to cross its airspace when carrying out missions over Libya.