Free Market - Core - SDI 2011

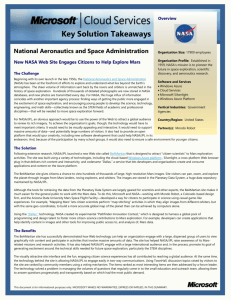

advertisement