Considering Class: Situational Factors in the Perception of Class

advertisement

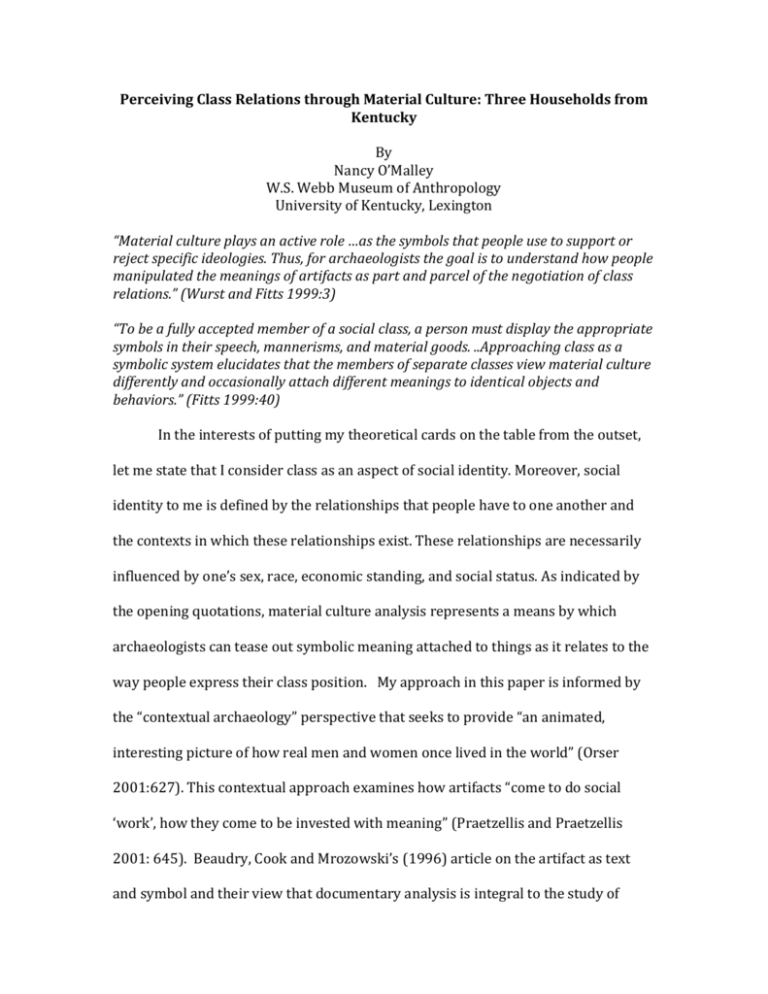

Perceiving Class Relations through Material Culture: Three Households from Kentucky By Nancy O’Malley W.S. Webb Museum of Anthropology University of Kentucky, Lexington “Material culture plays an active role …as the symbols that people use to support or reject specific ideologies. Thus, for archaeologists the goal is to understand how people manipulated the meanings of artifacts as part and parcel of the negotiation of class relations.” (Wurst and Fitts 1999:3) “To be a fully accepted member of a social class, a person must display the appropriate symbols in their speech, mannerisms, and material goods. ..Approaching class as a symbolic system elucidates that the members of separate classes view material culture differently and occasionally attach different meanings to identical objects and behaviors.” (Fitts 1999:40) In the interests of putting my theoretical cards on the table from the outset, let me state that I consider class as an aspect of social identity. Moreover, social identity to me is defined by the relationships that people have to one another and the contexts in which these relationships exist. These relationships are necessarily influenced by one’s sex, race, economic standing, and social status. As indicated by the opening quotations, material culture analysis represents a means by which archaeologists can tease out symbolic meaning attached to things as it relates to the way people express their class position. My approach in this paper is informed by the “contextual archaeology” perspective that seeks to provide “an animated, interesting picture of how real men and women once lived in the world” (Orser 2001:627). This contextual approach examines how artifacts “come to do social ‘work’, how they come to be invested with meaning” (Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001: 645). Beaudry, Cook and Mrozowski’s (1996) article on the artifact as text and symbol and their view that documentary analysis is integral to the study of material culture and vital for constructing context expresses my own perspective more eloquently than I can hope to. Lou Ann Wurst’s (1999: 8) characterization of class as internal relations “where the web of social relations makes up the whole, and the appearance of these relations are taken to be its parts” informed and influenced my analysis considerably. My analysis is purposely small scale, examining assemblages generated by single families living at particular times and places. While I acknowledge the Marxist definition of class and the very interesting analyses that stem from it, I do not invoke it here, partly because the assemblages I am using do not lend themselves to such an analysis and partly because I am viewing class as “a culturally and historically constructed identity” rather than “an objectively defined object in the world” (Ortner 1998:3). The assemblages I use in this paper are from three families living in Kentucky from the late eighteenth century to the first quarter of the twentieth century, each under very different circumstances. Hugh McGary brought his blended family to Kentucky in 1775 and settled at a defensible residential station in present day Mercer County for nine dangerous years of Indian attack, periodic deprivation, economic uncertainty and political upheaval. In the 1840s with permission granted by the parish priest, widow Mary Cassell built a house in Lexington, Kentucky on the corner of the Catholic cemetery where she lived with her daughter, son-in-law, grandson and two young slave children until she died in the early 1860s. Former slaves William and Emily Hummons moved to Lexington after the Civil War, built a house, and set about establishing a life as free people in a new social order. Each family had unique attributes that positioned them within the society in which they lived and influenced their relationships with their fellow citizens and their community. Each of the assemblages were deposited at different times in history. Two of the assemblages occurred in the same city while the other assemblage was in a rural locality. All of the assemblages were analyzed at the household level. Being able to analyze artifact assemblages that represent the discarded possessions of people whose names, and occupations you know and for whom you can often learn a considerable amount of detail is an enviable position to be in as an analyst. However, generalizing to larger issues of class relations remains a challenge precisely because of the variation in meaning attached to identical artifacts by different classes. We can, however, identify the types of relationships that each household experienced and search for possible material culture indicators of the classes these relationships suggest. The types of relationships experienced by the three households have commonalities and differences. In all three cases, each household experienced relationships at the familial level—for example, husband-wife, parentchild, or sibling-sibling. At the household level, the relationship between slaveowner and slave introduces a particular dynamic for two of the families. Other relationships that can be identified are those with one’s peers (people who are considered socially “equal” by various measures), one’s “betters” (people to whom one defers, willingly or unwillingly) and those of lesser social standing. These relationships are close up and personal, experienced frequently and require continuous adjustment in behavior, much of which may be essentially unconscious. At a broader social level, relationships may be recognized between individuals and institutions or a body of laws that regulate behavior. Archaeological assemblages associated with the three subject families are well suited to such a study. The McGary assemblage dates between 1779 and 1788. It is a tightly dated collection of artifacts that reflect life on the western frontier during the Revolutionary War and immediately after, a time and place of undeveloped local mercantile networks, hazardous living conditions, and a society in flux. Documentary sources for the McGary family include land grant records, county court order books, interviews of people who knew or knew of the family, and family genealogy, all bolstered by other documentary sources relevant to the time period and to Kentucky. The Cassell assemblage dates squarely within the antebellum period, covering 20+ years of urban living in a city of the upland south, at a time when Victorianism and the “cult of domesticity” was developing. Perhaps more importantly, the Cassell assemblage dates to the period when the so-called “middle class” was developing as society experienced the growth of new industries, businesses and professions. Historic maps, city directories and census records comprised the bulk of the documentary evidence relating to the family. The Hummons assemblage represents the postbellum period in the same city, a time of often perilous experience for a freed slave family. In the midst of a chaotic social setting, African-Americans struggled to obtain equal rights with whites but encountered many obstacles, such as segregated shopping venues, economic restrictions that made wealth accumulation difficult, and racist attitudes that hampered social advancement. Documentary sources for the family include their deed records, mortgages, an interview with a family descendant, census returns, historic maps, newspaper mentions, and marriage records, which are augmented by extensive research on the neighborhood in which they lived. The McGary Family Hugh McGary brought his family to Kentucky in the spring of 1775 as members of a party of settlers led by Daniel Boone. The family was a blended one, comprised of Hugh, aged 31, his wife Mary Buntin Ray McGary, aged 40, her three sons by her first husband, James (aged 14), William (aged 12) and John (aged 10), as well as her children by Hugh, Robert (aged 8), Daniel (aged 4) and Mary Ann (aged 1). They travelled in a large party of settlers, some well known to them as either relatives or friends, others perhaps less familiar. There may have been slaves in the party as well as Hugh McGary is recorded as a slaveowner in later records. They brought with them a substantial amount of livestock, including 40 horses by one account. Parting company from Boone and others who headed to Fort Boonesborough in present day Madison County, the McGarys and at least two other families set out for the James Harrod Boiling Spring settlement in present day Boyle County, Kentucky. At this point, the party experienced an all-too- familiar predicament—they became lost. Leaving the older boys at the mouth of Gilbert’s Creek with the livestock, the rest of the party pushed forward to find their destination, promising to return in a few days. The time stretched to two weeks before McGary could retrieve the boys and the livestock. This incident underscores a common condition of the frontier: settlers were in unfamiliar territory with only oral instructions and perhaps a few crudely drawn maps to guide them. They eventually settled at the site of Fort Harrod in present Mercer County, Kentucky, on September 8, 1775, some five months after the Revolutionary War began. Numerous families congregating at defensible forts or stations was standard procedure for Kentucky settlers during the war; this communal style of living provided safety in numbers and sanctuary for incoming settlers prior to the establishment of their own farms. The classic design of forts and stations was an enclosure of log cabins forming a square or rectangle and connected by sections of log stockade. Forts differed from station in scale, being usually larger, and housing settlers who often were strangers to one another and came from diverse backgrounds. Stations were generally headed by the man who claimed the land on which it stood and its inhabitants were often friends and relatives. Some form of defensibility was usually incorporated into the construction although it might not have taken the form of a stockade. Forts and stations served an important purpose as sanctuaries and defensible sites from external enemies during wartime. However, the crowded and unhygienic conditions of these enclosed defensive residences also exposed class differences and conflicts. Far from being a homogeneous population, settlers came from all walks of life and economic circumstances. Ethnic differences were readily noticed and judged; for instance, settlers of German origin were frequently described as poor hunters, stolid and single minded in their work habits and set apart by language barriers. Irish settlers were referred to as rowdy and prone to drink. Even settlers from different parts of the colonies were set apart by their dress, values, and habits; the term “cohee” was used to identify settlers who lived west of the Blue Ridge while a “tuckahoe” inhabited the lowlands of Virginia. Not only could a person “tell where a man was from, on first seeing him,” the encounters were sometimes hostile (Perkins 1998:85). Hugh McGary established his station in 1779 at Shawnee Springs where it was home to his immediate family, the Patrick Jordan family who stayed for five years and one or two other families who stayed for a few months until they could establish stations on their own land. Single young men serving as scouts in the local militia were periodically assigned to the station to help protect it. Slaves may also have lived at the station at various times. The social strife associated with living in forts or large stations among strangers was largely absent at McGary’s station but the social dynamics taking place here were complex, nevertheless. During the nine years that the McGary family lived at the site, Mary McGary died and Hugh remarried, the older children grew to adulthood and at least one of the sons married twice and had two children before leaving the station for his own farm in 1787. Hugh’s second wife bore two or three children while at the station. The site was abandoned in 1788 when McGary sold the land and moved elsewhere. The site assemblage, therefore, represents to a large extent, the belongings of the McGary family. Compared to the later assemblages considered in this paper, the McGary assemblage has lower frequencies and lesser diversity of artifacts. Settlers were limited in the amount of household goods that they could bring into the frontier. Traveling along the Wilderness Road limited loads to those that could be borne by human or animal power. Flatboat travel down the Ohio River allowed for the transport of more goods but, having disembarked at one of several landings, the trip inland to the area of earliest settlement posed the same logistical problems. Nevertheless, over time, enterprising businessmen devised ways to bring in goods of various kinds and families that could afford them could add to their household assemblages. Mobility in the form of horses also conferred an advantage to those who owned them since they could make periodic trips back east. McGary was particularly well travelled. He was sent to Fort Pitt (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania) in 1777, travelled to Natchez more than once and made frequent trips to Harrodsburg and Logan’s Station (present day Stanford, Kentucky) in addition to his travels associated with militia raids against various tribes (Hammersmith 2000:129-131). Any of these travels could have been a means by which the family acquired manufactured goods. An important distinction that relates to Hugh McGary’s class standing is his status as a landowner.The earlier a settler arrived, the better situated he was to acquire high quality land. Hugh McGary’s early arrival conferred a great advantage that he did not hesitate to exercise. He immediately began looking for land, settling on a prime piece of real estate about four miles from Fort Harrod at a spectacular system of freshwater springs known as Shawnee Springs. There he claimed 575 acres at a land court held at Fort Harrod on October 27, 1779. He also was successful in claiming other land in the area, some of which he kept for himself and some he assigned to other settlers. All told, he acquired a total of 3,626.5 acres of which he assigned (for a fee) 800 acres to other men. Although it took several years to finalize the title, he had control of a large quantity of land at an earlier date whose title was never challenged. In addition, he was a slaveowner and trader, he held high rank in the county militia, and he occupied a seat on the county court. All these attributes combined to place him in a relatively high class in frontier society in which he could potentially influence local politics, profit economically and take his place as a leader. His position among the settler elite also led to conflict with other settlers who had failed to acquire land and so were politically aligned with factions that opposed land policies practiced by Virginia, and approbation by those who held antislavery sentiments. His military rank also placed him in oppositional situations with soldiers of lesser rank and fellow officers who disagreed with his strategies in battle. On a personal level, Hugh McGary was sometimes impetuous, sensitive to criticism, and tempermental, leading to several recorded occasions where he was the catalyst for poorly conceived military strategies, physical altercations with other settlers, or other interpersonal disagreements. These behavioral traits eventually undercut his social standing but, for the period covered by his station occupation, he filled a leadership role as a junior officer in the militia and a member of the local county court, and was more prosperous than many other settlers. The McGary assemblage includes material evidence of document boxes (a padlock, key, decorative faceplates and a bat-wing style keyhole escutcheon) in which land grant records, money (represented by a “piece of eight”, a Spanish reale cut to 1/8 its original size), and other valuables were kept. Document boxes were the safes of their time; ownership of document boxes suggests the need to keep valuable portable property under lock and key. The McGary assemblage includes items such as English manufactured dishes, jewelry, buttons and other things that had to be purchased and were not made locally. Unlike settlers like young William Clinkenbeard who said, “My wife and I had neither spoon, dish, knife or anything to do with when we first began [married] life, only I had a butcher knife” (Beckner 1928), the McGary family had numerous eating implements, English refined ceramics in many different patterns, and a small quantity of Oriental porcelain. They may have been eating venison and other wild meats, foraging for wild edible plants and suffering periodic food shortages as virtually all settlers did, but when they did eat, they could serve their food on stylish dishes. Moreover, their clothing was embellished with buttons that had decorative designs rather than simply being plain and they owned jewelry such as fingerings and pins. Clothing was one of the ways that settlers placed others socially, as were language and manners (Perkins 1998:86). Perkins (1998:86) describes the experience of Mary Dewees who travelled to Kentucky from Philadelphia in 1788. Staying at a rough tavern, she discovered that “by our dress or Adress or perhaps boath [we] were favoured with a bed” while other less genteel guests slept on a dirt floor. Combined with archival evidence of McGary’s land and slave holdings, political appointments, military rank, and other indicators, his status and that of his family falls within a class that might be termed “landed gentry.” Material culture indicators that may be indicative of class include clothing items, patterned ceramic tableware, artifacts related to the storage of valuable portable property, and coinage. However, artifacts in a frontier context cannot stand alone in reconstructing class relationships. Archival evidence is necessary to corroborate class identity. Comparative assemblages from similar sites in the same time period are unfortunately unavailable for Kentucky but the McGary assemblage offers the promise of interesting associations between class position and artifact traits. Mary Cassell and her family According to the 1838 Directory of Lexington, Kentucky, Mrs. Mary Cassell was living on the corner of Spring and West High Streets. The identity of her husband has not been determined despite extensive archival research. She may have been a widow and appeared in the Directory because she was the head of her household. Her listing in the directory is intriguing. Her marital status is suggested by the use of the term “Mrs.” but her widowhood is implied by the absence of a man with the same surname living at the same address. A review of the other female names listed in the 1839 directory reveals some interesting patterns. Free women of color were nearly always listed by their first and last names without any title such as Miss or Mrs. and they were always listed with an occupation. White women were nearly always listed with their title, Mrs. or Miss, but inconsistently with either their first and last name or just the initials of their first name and their surname. Occupations were more frequently omitted than listed for white women. Of the 125 women listed in the directory, 68 white women were without occupation, compared to 41 white and 16 black women. No woman of color lacked an occupation. The occupations listed also cast light on the restrictions placed on women who had to make their own living (Table 1) Table 1. Female Occupations in the 1838-1839 Lexington Directory. Occupation White women Black women Dress maker 8 0 Tailoress 6 0 Seamstress 3 1 Milliner/hat trimmer 4 0 Laundress 0 13 Boardinghouse keeper 10 0 School mistress 2 0 Music teacher 1 0 Grocer 2 0 Morocco manufacturer 1 0 Shoe binder 0 1 Boot and shoe trimmer 1 0 Fancy store proprietor 1 0 Weaver 0 1 Cart proprietor 1 0 Mattress maker 1 0 The 1840 Census lists a ”Mrs. M.A. Casswell” who was head of a household containing six other females ranging in age from less than 5 to as old as 50 years. Of the seven, six were working in manufactures and trades (including, apparently, a child between 5 and 10 years of age, if the census is correct). Mrs. Cassell’s residency in a household comprised entirely of females, most of whom were working for a living, suggests that her financial position was precarious after her husband died, perhaps necessitating a boarding house arrangement. Moreover, she is listed in the 1840 census as head of household with no male present. Mrs. Cassell’s social position as represented by the 1838-39 directory and 1840 U.S. Census is ambivalent. If she was boarding the females who were living with her, why was that occupation not indicated in the directory as it was for other women (assuming her situation was the same in 1838-1839 as it was in 1840)? A search for repetitious listings for Mrs. Cassell’s address in the directory did not identify any of the females who were living with her at that address in the 1840 census. Nor were the trades in which the women were employed determined. While the precise circumstances of Mrs. Cassell’s living situation and status cannot be surmised with certainty, one interpretation of the evidence suggests that being a widow in the mid-nineteenth century, particularly if your deceased husband had not been a wealthy man who could leave a wife in financial comfort, was an ambiguous social position. Financial constraints undoubtedly had an impact on one’s ability to acquire material goods that conveyed class position based on economic standing but social standing recognized by one’s “respectability” and adherence to certain social customs may have allowed a higher class status than might otherwise be obvious. Another possibility that might explain Mrs. Cassell’s occupation is not capable of proof with available evidence but deserves mention. A house full of women all working without evidence of husbands might have been a brothel. The difficulty with this interpretation is the fact that Mrs. Cassell received permission from the local parish priest to build a house on the Catholic cemetery lot in the 1840s. Given the church’s and society’s stance against prostitution, it seems unlikely that a priest would allow a prostitute to build a house on church property even if she had reformed. A quit claim deed filed in 1857 between Mary Ann Cassell and the Catholic Church provides further clarification. Mrs. Cassell identified herself as a widow and acknowledged that the Pastor of St. Peters Church, Rev. E. McMahon, “in consideration of his desire to do me an act of kindness”, allowed her to enclose and build a house on part of the church’s cemetery lot and live there during her lifetime, thus saving her the expense of buying land. The deed was filed many years after the agrrangement was made in order to formally affirm the church’s legal title to the lot on which Mrs. Cassell built her house. The assemblage considered in this paper was excavated at this house. She was residing here in 1850 with her son-in-law, Lucullus Lawes, a coachmaker who was probably the breadwinner of the family, her daughter, Mary L. Lawes, a 4-year-old girl named Mary Hulls of unknown relationship and two slave children. Mrs. Cassell was not listed with an occupation but she was listed as head of household over her son in law. She declared a real estate value of $350.00 which represented the value of her house. Ten years later, she was listed as a dependent in her son in law’s household, a reversal that may have been a result of her advanced age. She also no longer owned slaves by 1860. Mrs. Cassell’s assemblage reflects her urban location, close to many mercantile outlets that offered an abundance of manufactured goods. Although undecorated ceramics are the most numerous category, the assemblage also includes several dozen handpainted and transferprinted patterns, most of which were likely imported from England. A small quantity of Oriental Export porcelain is also present. While pattern diversity is relatively high in the Cassell assemblage, vessel form diversity is relatively low. The ceramic assemblage suggests that purchases were made more often by the piece or in limited numbers of a single form such as plates or cups rather than sets with numerous vessel forms. Likewise, the glass tableware included some pressed patterns but was not elaborate. Clothing parts such as jet buttons suggest an interest in fashionable attire as does the presence of jewelry containing paste gemstones but most of the buttons are very simple opaque glass examples. While Mrs. Cassell did not own land, she did own her house and, for some years, two slaves; she also did not have to work for a living, being able to rely on her son in law to support her and his family. While archival evidence does not support a lavish or wealthy lifestyle for the Cassell household, material evidence suggests a modestly genteel lifestyle. Lucullus Lawes’ occupation as a coachmaker or coach trimmer identifies him as a skilled craftsman; however, the 1860 census record for the family lists neither personal nor real estate values even though city directory records confirm their continued occupation of the site. The family may have been constrained in their purchases of stylish goods by their economic situation since there appears to have only been a single breadwinner, the son in law, for the family, which expanded to include a grandson by 1860. Identifying a class for the Cassell/Lawes family is problematical. On the one hand, their acquisition of decorated ceramic and glass tableware for dining falls in line with the social dining conventions of the time and suggests their placement somewhere within the middle class. On the other hand, Lucullus Lawes’ occupation is more suggestive of the working class since he was engaged in construction of carriages, arguably a “blue collar” job. However, as Sherry Ortner (1998) has pointed out,, a working class designation is often rejected by individuals who may well describe themselves as working men but think of themselves as middle class. This case, more than the other two, epitomizes the difficulty of defining class, particularly the middle class which Ortner (1998:8) describes as “the most slippery category.” Ortner’s (1998:7) labelling of the “largely-white-working-class-thatthinks-of-itself-as-middle-class” as lower middle class may be a fairly good fit here. The salient indicators for assignment to the middle class, I suggest, are the high ceramic but low vessel diversity, the fact that the women in the family did not work outside the home but were supported by the male family member, ownership of their house despite its modest value, and the ownership of two slave children for an unknown period of time but probably not more than a few years, at most. William Hummons and family William and Emily Hummons were a young married couple when they bought a lot in Lexington and built a house around 1869 (O’Malley 1996, 2003). They were married in 1864 by a black Baptist preacher related to Emily while they were living as slaves on a farm east of Lexington. After the war ended, the couple moved to Lexington where William worked initially as a wagon driver then became a blacksmith and farrier by 1880, an occupation he probably kept until his death in 1898. Emily stayed at home to rear their four daughters but in 1900, she was working as a laundress and later still as a cook for private families; it appears probable that her return to the workplace was related to her having been widowed without sufficient economic support. Although William and Emily remained in working class jobs, they took pains to see that their daughters were educated; at least two of them became teachers. One of the daughters was a member of the Lexington chapter of the National Association of Colored Women in the 1920s. The family attended a large black Baptist church; the daughters were involved in cultural pursuits such as musical recitals and recitations. Emily was a member of Queen Victoria’s Court, the female auxiliary of the Knights of Templar; William must have been a member of the Knights of Templar as well. Emily’s and William’s race and former slave status as well as the post-Civil War context in which they lived placed them in a highly ambiguous social situation. The post-Civil War period in Lexington was chaotic in many respects. Former slaves had to negotiate new relationships with whites, many of whom were outraged at the demise of the social order they once had taken for granted. Racially motivated violence was common, good jobs were scarce, and any misstep could result in ugly consequences. The black community reacted by closing ranks and creating a subculture that operated alongside but below the radar of the dominant white culture. Thus, the racist climate produced segregated residential patterns that had not existed prior to the Civil War and had the effect of creating neighborhoods where black families could live together and support one another, unmolested by white interference. Outside these neighborhoods, however, class relations shifted and readjusted to the realities of working for white employers, encountering potentially hostile strangers on the street or in the market, or running afoul of law enforcement officers. Class relations for the Hummons family were particularly complex. As freed slaves, they came from a situation where they had little or no control over their movements, the fruits of their labor, living conditions, or other civil rights that people who have never experienced enslavement expect and take for granted. Their relationships with other freed slaves must have been informed by this shared experience and the reaction of whites to their emancipation and the abolishment of slavery. The family lived in a time and place where they were prohibited from shopping in certain stores, limited to jobs that paid low wages and were often only seasonally available, and constrained in other ways from participating in activities that might allow them to ascend the class ladder. William and Emily Hummons also had relationships with their respective employers that not only directly affected their income but may also be made materially visible in their assemblage by the presence of household items that were given to them, particularly as a result of Emily’s employment as a private cook. Their relationships in the black community through their church, benevolent society memberships, or other organizations in which they or their children participated stand in contrast to their standing among the white community. The influence of the racialized social landscape in which the Hummons family is, moreover, inescapable. Wilkie’s (2001: 111) invocation of Habermas’ term lebenswelt (lifeworld) and his view that “individuals interpret their surroundings through the observation and analysis of social action” and that “they turn to their personal expericences to determine how they are to navigate through the social landscape” becomes a useful lens through which to examine the Hummons’ lived experience through the artifacts they used. The Hummons assemblage represents the household cycle of their early marriage years, the rearing of their children, William’s death in 1898 and Emily’s years as an elderly widow until her death in 1921. Standing in front of their modest, frame shotgun house, one might predict that the material goods inside that house would be similarly modest in diversity and quantity, but this was far from the case. Elaborate and varied ceramic and pressed glass tablewares with a high diversity of patterns and vessel forms suggest an interest in setting an elaborate table; decorative clothing parts and toiletry items indicate the desire to present a very fashionable and well groomed image; artifacts related to household furnishings suggest a desire to have a well appointed house. All these trends in the artifact assemblage belie the family’s modest financial standing. The motivation behind acquisition of numerous and elaborate household and personal goods may be interpreted in various ways. Bell’s (2002) research on emulative behavior and empowerment offers one possible interpretation. While the adoption of the material culture of people whose socioeconomic standing is perceived as higher requires the expenditure of funds that might be better spent on other investments, buying things on the secondhand market or receiving them as part of one’s pay mitigates the impact that such acquisition has on one’s financial resources. Moreover, the display of genteel household furnishings and fashionable attire conveys a sense of appreciation for “nice things” and an understanding of proper etiquette and social behavior. This strategy could have social benefits both within the black and the white community, although the benefits may have been different. Acquisition of elaborate household furnishings and accoutrements could even be interpreted as a conscious act of resistance against social attitudes held by the dominant white culture that sought to keep African-Americans in an inferior societal position. The material evidence is further bolstered by the women’s participation in local self-help organizations that encouraged the uplifting of the race, attendance at a prominent black church, and ownership and improvement of their house and lot. The Hummons family may well have occupied a dual class standing that was higher in the black community and was less contingent on how much money they had or their family background and more on their personal character and industry. Their class standing among whites was likely quite different, defined more by convictions of white superiority, the relative position of a blacksmith or a private cook on the occupational ladder, and even ignorance of the family’s accomplishments and aspirations. Yet the family, particularly the women, clearly connected material goods with perceptions of social position and gentility, and allocated limited financial resources to acquire these material indicators. Notably, the presence of refined ceramics and glass tableware manufactured many years before their occupation began suggests secondhand acquisition, either through purchase at estate auctions or resale outlets or gifts by employers (both common venues for acquiring used goods). The three assemblages considered here underscore the complexity implicit in inferring class relations in material culture. The McGary family’s class standing is more readily perceptible in the archival record than the archaeological since access to material goods on the frontier was limited. However, even their relatively small assemblage contains evidence of dress conventions, storage of valuables under lock and key and dining behavior that identify them as closer to the elite than the nonelite. The Cassells and the Hummons had access to an abundance of material goods but were constrained by their financial position, and, in the Hummons’ case, possibly by other constraints imposed by racial prejudice. Yet the Hummons assemblage is quite different from the Cassell assemblage for reasons that are not immediately obvious without considering other sources of evidence. The Cassell assemblage is simpler, less overtly stylish and more utilitarian with relatively less evidence of elaborate dining behavior or fashionable dress. The Hummons assemblage, on the other hand, shares many similarities with upper class white assemblages such as Henry Clay’s Ashland Estate in the form of elaborate dining artifacts, fashionable clothing fasteners,toiletry items and home furnishings. The presence of artifacts, particularly ceramics, that were manufactured many years before the date of the occupation, suggests a mechanism for acquiring more elaborate dishes secondhand, thus saving money but still enabling the buyer to express genteel and fashionable tastes. In all three cases, the integration of archival data with the material culture evidence is essential to identifying social class in a more nuanced way. Factors of race, sex, occupational status and living situation are important in identifying class relationships. Investigating class through material culture, while fruitful, is greatly benefitted by including archival information that illuminates social relationships, memberships in social organizations, participation in a ranked military system or other information that has to do with social classifications in which people are placed. Further, considering class within the context of time and place provides a useful grounding for drawing conclusions about the social dynamics operating in the short term in individual assemblages. References Cited Beaudry, Mary C., Lauren J. Cook, and Stephen A Mrozowski 1996 Artifacts and Active Voices: Material Culture as Social Discourse. pp. 272-310. In Images of the Recent Past: Readings in Historical Archaeology. edited by Charles E. Orser, Jr. Altamira Press, Walnut Creek, California. Beckner, Lucien 1928 Reverend John D. Shane’s Inverview with Pioneer William Clinkenbeard. Filson Club History Quarterly 2:95-128. Bell, Alison 2002 Emulation and Empowerment: Material, Social, and Economic Dynamics in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Virginia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6(4): 253-298. Fitts, Robert K. 1999 The Archaeology of Middle-Class Domesticity and Gentility in Victorian Brooklyn. Historical Archaeology 33(1):39-62. Hammersmith, Mary Powell 2000 Hugh McGary, Senior, Pioneer of Virginia,North Carolina, Kentucky and Indiana. Nodus Press, Wheaton, Illinois. McCabe, Julius P. Bolivar 1839 Directory of the City of Lexington and the County of Fayette for 1838 & 1839. J.C. Noble, Printer, Hunt’s Row, Lexington, Kentucky. O'Malley, Nancy 1996 Kinkeadtown: Archaeological Investigation of an African-American Neighborhood in Lexington, Kentucky. University of Kentucky Department of Anthropology, Archaeological Report 377, Lexington. O’Malley, Nancy 2003 The Pursuit of Freedom: The Evolution of Kinkeadtown, An African-American Post-Civil War Neighborhood in Lexington, Kentucky. Winterthur Portfolio 37(4). Orser, Charles E., Jr. 2001 The Anthropology in American Historical Archaeology. American Anthropologist, New Series, 103 (3):621-632. Ortner, Sherry B. 1998 Identities: The Hidden Life of Class. Journal of Anthropological Research 54(1):1-17. Perkins, Elizabeth A. 1998 Border Life: Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. Praetzellis, Adrian and Mary Praetzellis 2001 Mangling Symbols of Gentility in the Wild West: Case Studies in Interpretive Archaeology. American Anthropologist, New Series, 103(3): 645-654. U.S. Census Bureau 1840 Population and Slave Census for Fayette County, Kentucky. 1850 Population and Slave Census for Fayette County, Kentucky. 1860 Population and Slave Census for Fayette County, Kentucky. Wilkie, Laurie A. 2001 Race, Identity and Habermas’s Lifeworld. pp. 108-124. In Race and the Archaeology of Identify, edited by Charles E. Orser’s Jr., The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. Wurst, LouAnn and Robert K. Fitts 1999 Introduction: Why Confront Class? Historical Archaeology 33(1): 1-6. Wurst, LouAnn 1999 Internalizing Class in Historical Archaeology. Historical Archaeology 33(1):721.