J.G. Ballard, 1930-2009 Jimmy Ballard grew from a naive twelve

advertisement

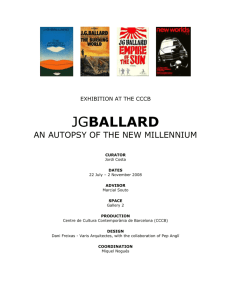

J.G. Ballard, 1930-2009 Jimmy Ballard grew from a naive twelve-year-old to a perhaps prematurely wise fourteen-year-old during his two-and-a-half years spent in the camp. He was never separated from his parents and sister, and the physical privations the family underwent were not especially severe; nevertheless, the contrast with their previous wealthy lifestyle was extreme, awakening in the young Ballard a lifelong sensitivity to dislocations, sudden reversals, paradoxes, and ironies. A few months after the liberation, in late 1945, he was "repatriated" to England, a country he had never seen, together with his mother and sister (his father did not finally return to the west until after the Communist takeover of China in 1949). For four or five years, Ballard was a short-story writer, a period which climaxed in 1960 with the appearance of his remarkable tale "The Voices of Time." Set amidst desert landscapes, in a moodily-depicted near-future world situated in a larger universe that was running down, it introduced its readers to what Amis was later to call "the inner reaches of Ballard-land." After more than twenty magazine short stories, his first four books arrived in a burst in 1962, the novels The Wind from Nowhere and The Drowned World, and the collections The Voices of Time and Billenium, all published as 50-cent paperback originals by Berkley Books of New York. When The Drowned World appeared as a hardcover in Britain early in 1963, it was very well received, as were the two follow-up story collections issued by Gollancz, especially The Terminal Beach (1964). On the strength of this, and as the stories continued to spill out, he became a full-time writer. Gradually emerging from that nest in 1965-1966, Ballard became a participant in the Swinging Sixties. His novels The Drought and The Crystal World appeared (both largely written before his wife's death); he became Prose Editor of the poetry magazine Ambit; and his friendship with the new, young editor of New Worlds, Michael Moorcock, led to Ladbroke Grove parties, occasional drugs, and new women friends. Ballard was encouraged to experiment in his writing, beginning a "non-linear" phase with his story "You and Me and the Continuum." He became something of a guru to a circle of younger sf writers, some of them visiting Americans such as Thomas M. Disch and Pamela Zoline. One of Moorcock's editorials was entitled "Ballard: The Voice." Stories appeared in Encounter, The Transatlantic Review, and various small magazines. But no new novel would appear for seven years. His next significant book was The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), a collection of the nine so-called "condensed novels" plus half a dozen brief prose satires (the latter included his most infamous title, "Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan"). His next novel, Crash (1973), was written in a state of what he later described as "willed madness." Enlarging on a theme first broached in the preceding book -- the psycho-sexual role of the automobile in all our lives -- it was to be his most extreme work, a Jean Genet-like rhapsody on all the conceivable erotic overtones of the car crash. (It was written at the time a motorway extension was being built past the end of his street in Shepperton.) A fortnight after he delivered the manuscript, in February 1972, Ballard experienced his own first car crash while coming home late one night from central London -- "a case of life imitating art," as he later said. Fortunately, he was not badly hurt (and no one else was involved), but he was banned from driving for a year, during which he was inspired by this event and its aftermath to write another car-crash novel, Concrete Island (1974). Crash itself received poor reviews in the British press, but it became a succes d'estime in France and elsewhere, and more than two decades later it formed the basis of a provocative film directed by David Cronenberg. In 1984 he published his largest novel to date, Empire of the Sun. It became a UK bestseller, gained him a whole new readership, and won the Guardian fiction prize. Famously, it failed to win the Booker Prize, despite being the bookies' favourite (and the reviewers'). A heavily fictionalized version of his own childhood in Shanghai, it was hailed as a major "war novel," and it is likely to be the book upon which much of his reputation will rest. Ballard revisited North America for the first time since his RAF days in order to attend the Los Angeles premiere of the Steven Spielberg film version of the novel in December 1987. A quasi-sequel followed, The Kindness of Women (1991), which was more of a sequence of short stories than a novel, based on his own life story from 1937 to 1987. Like Empire... it represented a fantastication of his autobiography, which it would be unwise to take too literally in all its details. But it was a powerful and moving book, which gained high praise from the UK critics. To promote its launch, and at the behest of the BBC, he undertook another of his rare travels, his first visit to Shanghai since childhood, where interviews with him were shot for a memorable TV "Bookmark" programme entitled "Shanghai Jim." Other late novels included The Day of Creation (1987), a psychological fantasy set in an imaginary Africa; Rushing to Paradise (1994), a not entirely successful satire-cum-horror story set in an equally imaginary South Seas; Cocaine Nights (1996), the first of his special brand of crime-and-detection stories, set in the south of Spain; and Super-Cannes (2000), a crime novel set in a huge business park on the French Riviera. The last was the best -- sly, witty, and extraordinarily inventive in its attack on eve-of-Millennium complacency. His Complete Short Stories appeared as a 1200-page volume in 2001, and must rank as one of his greatest books: if he had never written a novel this would still make Ballard a major writer. But there were to be no more short stories after the mid-1990s, and his last two novels, Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), showed failing powers, for all their incidental felicities. Both were set in Britain, and represented an imaginative coming home -- despite being slightly off-key, even old-fashioned. Nevertheless, they are part of a hugely significant body of work, which has reflected the experience of much of the twentieth century in a myriad ways. His last book, the short but intensely moving memoir Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton (2008) -- in which he revealed the news of his terminal illness to the world -- was received with acclaim. From André Breton What is Surrealism? (A lecture given in Brussels on 1st June 1934) SURREALISM, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express, verbally, in writing, or by other means, the real process of thought. Thought's dictation, in the absence of all control exercised by the reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations. ENCYCL. Philos. Surrealism rests in the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association neglected heretofore; in the omnipotence of the dream and in the disinterested play of thought. It tends definitely to do away with all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in the solution of the principal problems of life. In the course of many attempts I have made towards an analysis of what, under false pretences, is called genius, I have found nothing that could in the end be attributed to any other process than this: Heraclitus is surrealist in dialectic. Swift is surrealist in malice. Sade is surrealist in sadism. Baudelaire is surrealist in morals. Rimbaud is surrealist in life and elsewhere. Carroll is surrealist in nonsense. Picasso is surrealist in cubism. We still live under the reign of logic... But the methods of logic are applied nowadays only to the resolution of problems of secondary interest. The absolute rationalism which is still the fashion does not permit consideration of any facts but those strictly relevant to our experience. Logical ends, on the other hand, escape us. Needless to say that even experience has had limits assigned to it. It revolves in a cage from which it becomes more and more difficult to release it. Even experience is dependent on immediate utility, and common sense is its keeper. Under colour of civilization, under pretext of progress, all that rightly or wrongly may be regarded as fantasy or superstition has been banished from the mind, all uncustomary searching after truth has been proscribed. It is only by what must seem sheer luck that there has recently been brought to light an aspect of mental life—to my belief by far the most important—with which it was supposed that we no longer had any concern. All credit for these discoveries must go to Freud. Based on these discoveries a current of opinion is forming that will enable the explorer of the human mind to continue his investigations, justified as he will be in taking into account more than mere summary realities. The imagination is perhaps on the point of reclaiming its rights. If the depths of our minds harbour strange forces capable of increasing those on the surface, or of successfully contending with them, then it is all in our interest to canalize them, to canalize them first in order to submit them later, if necessary, to the control of the reason. I believe in the future transmutation of those two seemingly contradictory states, dream and reality, into a sort of absolute reality, of surreality, so to speak. I am looking forward to its consummation, certain that I shall never share in it, but death would matter little to me could I but taste the joy it will yield ultimately. It should be understood that the real is a relation like any other; the essence of things is by no means linked to their reality, there are other relations besides reality, which the mind is capable of grasping and which also are primary, like chance, illusion, the fantastic, the dream. These various groups are united and brought into harmony in one single order, surreality... This surreality—a relation in which all notions are merged together—is the common horizon of religions, magic, poetry, intoxications, and of all life that is lowly—that trembling honeysuckle you deem sufficient to populate the sky with for us.