HPSG without PS - Richard (`Dick`) Hudson

advertisement

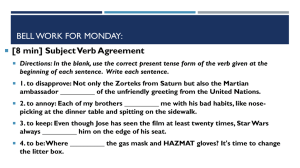

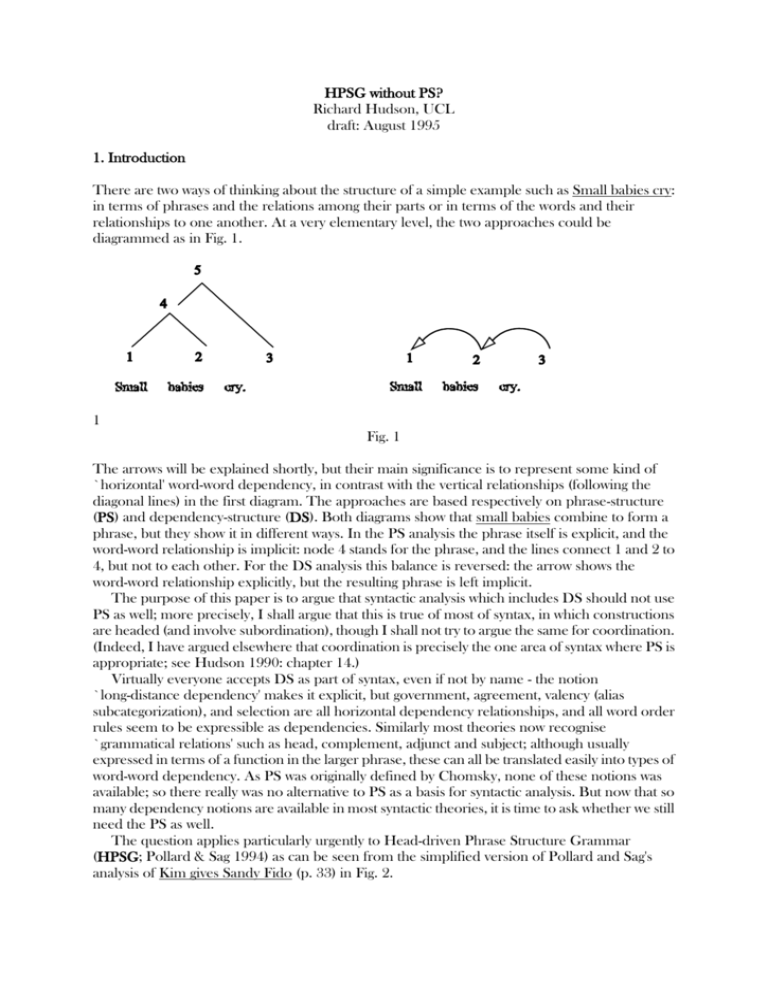

HPSG without PS? Richard Hudson, UCL draft: August 1995 1. Introduction There are two ways of thinking about the structure of a simple example such as Small babies cry: in terms of phrases and the relations among their parts or in terms of the words and their relationships to one another. At a very elementary level, the two approaches could be diagrammed as in Fig. 1. 1 Fig. 1 The arrows will be explained shortly, but their main significance is to represent some kind of `horizontal' word-word dependency, in contrast with the vertical relationships (following the diagonal lines) in the first diagram. The approaches are based respectively on phrase-structure (PS) and dependency-structure (DS). Both diagrams show that small babies combine to form a phrase, but they show it in different ways. In the PS analysis the phrase itself is explicit, and the word-word relationship is implicit: node 4 stands for the phrase, and the lines connect 1 and 2 to 4, but not to each other. For the DS analysis this balance is reversed: the arrow shows the word-word relationship explicitly, but the resulting phrase is left implicit. The purpose of this paper is to argue that syntactic analysis which includes DS should not use PS as well; more precisely, I shall argue that this is true of most of syntax, in which constructions are headed (and involve subordination), though I shall not try to argue the same for coordination. (Indeed, I have argued elsewhere that coordination is precisely the one area of syntax where PS is appropriate; see Hudson 1990: chapter 14.) Virtually everyone accepts DS as part of syntax, even if not by name - the notion `long-distance dependency' makes it explicit, but government, agreement, valency (alias subcategorization), and selection are all horizontal dependency relationships, and all word order rules seem to be expressible as dependencies. Similarly most theories now recognise `grammatical relations' such as head, complement, adjunct and subject; although usually expressed in terms of a function in the larger phrase, these can all be translated easily into types of word-word dependency. As PS was originally defined by Chomsky, none of these notions was available; so there really was no alternative to PS as a basis for syntactic analysis. But now that so many dependency notions are available in most syntactic theories, it is time to ask whether we still need the PS as well. The question applies particularly urgently to Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG; Pollard & Sag 1994) as can be seen from the simplified version of Pollard and Sag's analysis of Kim gives Sandy Fido (p. 33) in Fig. 2. 2 Fig. 2 The most interesting thing about this diagram is the way the verb's structure cross-refers directly to the nouns by means of the numbers [1], [2] and [3]. These cross-references are pure DS and could be displayed equally well by means of dependency arcs. Almost equally interesting is the way in which the verb shares its class-membership, indexed as [4], with the VP and S nodes. An even simpler way to show this identity would be to collapse the nodes themselves into one. The only contribution that the phrase nodes make is to record the word-word dependencies via their `SUBCAT' slots: the top node records that the verb's subcategorization requirements have all been met (hence the empty list for SUBCAT), while the VP node shows that it still lacks one dependent, the subject. This separation of the subject from other dependents is the sole independent contribution that PS makes in this diagram; but why is it needed? Pollard and Sag argue persuasively (Chapter 6) against using the VP node in binding theory, they allow languages with free constituent order to have flat, VP-less structures (40), and in any case HPSG recognises separate functional slot for subjects (345). It is therefore important to compare the HPSG diagram in Fig. 2 with its pure-DG equivalent in Fig. 3? 3 Fig. 3 What empirical difference is there between these two diagrams? What does Fig. 3 lose, if anything, by not having a separate node for the sentence? Could an analysis like Fig. 3 even have positive advantages over Fig. 2? Questions like these are hardly ever raised, less still taken seriously. Pollard and Sag go further in this respect than most syntacticians by at least recognising the need to justify PS: But for all that a theory that successfully dispenses with a notion of surface constituent structure is to be preferred (other things being equal, of course), the explanatory power of such a notion is too great for many syntacticians to be willing to relinquish it. (p. 10) Unfortunately they do not take the discussion further; for them the `explanatory power' of PS is self-evident, as it no doubt is for most syntacticians. The evidence may be robust and overwhelming, but it should be presented and debated. A reading of the rest of Pollard and Sag's book yields very few examples of potential evidence. PS seems to play an essential role only in the following areas of syntax: in adjunct recursion (55-6), in some kinds of subcategorization where S and VP have to be distinguished (125), in coordination (203), in the analysis of internally-headed relative clauses, for which they suggest a non-headed structure with N' dominating S (233). Apart from coordination (where, as mentioned earlier, I agree that PS is needed) the PS-based analysis is at least open to dispute, though the dispute may of course turn out in Pollard and Sag's favour. The question, then, is whether a theory such as HPSG which is so well-endowed with machinery for handling dependencies really needs PS as well. My personal view is that this can now be thrown away, having served its purpose as a kind of crutch in the development of sophisticated and explicit theories of syntax; but whether or not this conclusion is correct, our discipline will be all the stronger for having debated the question. The rest of the paper is a contribution to this debate in which I present, as strongly as I can, the case for doing away with PS. The basis for my case will not be simply that PS is redundant, but that it is positively harmful because it prevents us from capturing valid generalisations. My main case will rest on the solutions to two specific syntactic problems: the interaction of ordinary wh-fronting with adverb-fronting as in 0, and the phenomenon in German and Dutch called `partial-VP fronting', illustrated by 0. (1) Tomorrow what shall we do? (2)Blumen geben wird er seiner Frau. Flowers give will he to-his wife. `He'll give his wife flowers.' First, however, I must explain how a PS-free analysis might work. 2. Word Grammar My aim as stated above is `to argue that syntactic analysis [of non-coordinate structures] which includes DS should not use PS as well'. Clearly it is impossible to prove that one PS-free analysis is better than all possible analyses that include PS, so the immediate goal is to compare two specific published theories, one with PS and the other without it, in the hope of being able to isolate this particular difference from other differences. Fortunately there are two such theories: HPSG and Word Grammar (WG; see Hudson 1984, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, forthcoming; Fraser and Hudson 1992; Rosta 1994). Apart from the presence of PS in HPSG and its absence from WG, the two theories are very similar: both are `head-driven' in the sense that constructions are sanctioned by information on the head word; both include a rich semantic structure in parallel with the syntactic structure; both are monostratal; both are declarative; both make use of inheritance in generating structures; neither relies on tree geometry to distinguish grammatical functions; both include contextual information about the utterance event (e.g. the identities of speaker and hearer) in the linguistic structure; and perhaps most important of all for present purposes, both allow `structure sharing', in which a single element fills more than one structural role. Admittedly there are some theoretical differences as well: HPSG allows phonologically empty elements, HPSG distinguishes complements from one another by means of the ordered SUBCAT list rather than by explicit labels such as `object'. And not surprisingly there are disagreements in published accounts over the vocabulary of analytical categories (e.g. Pollard and Sag's `specifier' and `marker') and over the analysis of particular constructions (e.g. Hudson's analysis of determiners as pronouns and total rejection of case for English; see Hudson 1990: 268ff, 230ff; 1995a). However these differences, both theoretical and descriptive, are only indirectly related to the question about the status of PS, so we can ignore them for present purposes. One problem in comparing theories is to find a notation which does justice to both. The standard notation for HPSG uses either attribute-value boxes-within-boxes or trees, both of which are specific to PS, whereas DS structures are usually shown in WG by means of arrows between words whose class-membership is shown separately. To help comparison we can start by using a compromise notation which combines WG arrows with the HPSG unification-based notation, so that the information supplied by the grammar (including the lexicon) will be a partial description of the structures in which the word concerned may be used. For example, a noun normally depends on another word, to which it is connected by an arrow, and (obviously) can be used only at a node labelled `noun'; so Mary emerges from the grammar with the point of an arrow (whose shaft will eventually connect it to the word on which it depends), and also with the label `N' for `noun' (as well as `nN' for `naming noun', alias `proper noun'). In terms of morphosyntactic features it is singular, i.e. `[sg]'. A simple way of showing this information is by an entry like 0: (3) Mary N, nN [sg] For some words the grammar supplies a little more information. For example, deeply must be an adjunct (abbreviated to `a') of whatever word it depends on, and he must be subject (`s') of a tensed (`[td]') verb (which typically follows it). (4) -a deeply Av (5) he sN, pN V [td] For a slightly more interesting word consider loves. As in HPSG this is supplied with a valency consisting of a singular subject and any kind of noun as object. These requirements will eventually be instantiated by dependencies to some other word, which we show by a labelled dependency arrow. The English word-order rules fix their (default) positions, hence their positions to the left and right of loves in the entry. Unlike the previous examples, loves can be the `root' of the whole sentence, so it does not need to depend on anotehr word (though it may depend on one, in which case it is the root of a subordinate clause); this is shown by the brackets above the top arrow. (6) () N s- loves -o N [sg] V Putting these four entries together generates the structure for He loves Mary deeply in Fig. 4. 4 Fig. 4 Word order is handled, as in HPSG, by means of separate `linear precedence' statements. Some apply to very general patterns, the most general of all being the combination of any word with its `anchor' (the word on which it depends1). By default the anchor comes first in English, though this default may be overridden by increasingly specific patterns. At the extreme of 1The word anchor has not been used before in this sense, so far as I am aware. The normal term in dependency analysis is either head or regent, and I have always used head in my own work. However it has caused a great deal of confusion for readers familiar with PS uses of the same term. For example, in a PP such as with great care, the `head' of great care is care for PS but with in DS. (More precisely, with is the head of care, but the looser terminology is tempting.) This confusion is a potentially serious problem and best avoided. In any case, the notion `head' isn't very helpful as a metaphor for word-word dependencies. Regent is tied to complements and subjects which are `governed' by the word on which they depend, so it brings false expectations for adjuncts. The metaphor behind the word anchor is that the sentence-root is a fixed, firm, `anchor' for the words which depend on it, each of which then acts as an anchor for the words that depend on it, and so on recursively along each chain of dependencies. specificity are combinations of specific lexical items, which we can illustrate with the adverb deeply. Normally this follows a verbal anchor as in 0-0, but it can precede the verb resent as in 0: (7) I love her deeply *I deeply love her. (8) I slept deeply. *I deeply slept. (9) We looked deeply into each other's eyes. *We deeply looked into each other's eyes. (10)I resent the suggestion deeply. I deeply resent the suggestion. This idiosyncrasy can be shown by a special lexical entry for the sequence deeply resent, supplementing the normal entry: (11) () deeply a- resent -o N Av V This example illustrates an important general characteristic of WG, which it again shares with HPSG. Default inheritance and unification allow complex and specific entries to be composed on the basis of much more general entries, with the consequence that there is no clear division between `the lexicon' and `the grammar'. In WG the basic units of grammatical description are in fact elementary propositions such as those in 0. (12) resent is a verb. resent has an object. The object of a verb is a noun. A word's anchor is obligatory. A verb's anchor is optional. A word follows its anchor. deeply is an adverb. An adverb may depend on a verb. deeply may both depend on resent and precede it. Only the last of these propositions is specific to the sequence deeply resent; but all the rest are available in the grammar, and when applied to this sequence they generate the more complex structure in 0. Even at this elementary stage of explanation we can illustrate one of the positive disadvantages of PS. In a PS-based analysis, deeply is the head of an adverb-phrase and resent is the head of a verb-phrase, so the combination is in fact not a combination of words, but of phrases. In a tree-structure, the two words are likely to be separated by at least one AP and two VP nodes. These cannot simply be ignored in a lexical entry, because they are part of the definition of the relationship between the words. In contrast, a pure-DS analysis shows the words themselves as directly related to each other. A similar problem arises with lexically selected prepositions such as the with required by cope or the on after depend, which can be handled very simply and directly in WG (with `c' standing for `complement'). (13)( ) cope -c with V P In contrast, PS imposes a PP node between the verb and the preposition, so the only sister node available for subcategorization by the verb is labelled simply PP; but cope does not simply take a PP, it takes one headed by with. Pollard and Sag discuss the fact that regard lexically selects a PP headed by as, but their suggestion that the relevant phrases could be identified by the feature [+/AS] (ibid: 110) is hard to take seriously. Similarly, stop requires a subordinate verb to be a present participle, which can easily be expressed in a DS entry as a restriction imposed directly by one word on the other: (14) ( ) stop -c V V [prpt] But if PS is available the first verb's sister is the VP headed by the participle, so the latter's inflectional features have to be projected up to the phrasal node. The problem in each case is that the phrase node is a positive hindrance to satisfactory analysis. The problems created can of course be solved by projecting the head word's features onto the phrase; but the PS is part of the problem, not of the solution. 3. Structure sharing and (dis)continuity As mentioned earlier, perhaps the most important characteristic of HPSG and WG is the notion of `structure sharing'. (`It is not going too far to say that in HPSG structure sharing is the central explanatory mechanism ...', Pollard and Sag 1994:19) In both theories virtually all the major complexities of syntactic structure require some kind of structure sharing. We start with a simple example of subject-to-subject raising, which I shall assume needs no justification. The entry for (intransitive) stop shows the raising as structure sharing whereby the two verbs share the same subject: (15) () N s- stop -c V ___ s _/[prpt] The sharing appears in sentence structure as two dependencies converging on the same word as in the two diagrams of Fig. 5. The second diagram shows the recursive application of raising where stop is combined with another raising verb, the auxiliary have. 5 Fig. 5 Structures such as this are a major innovation in dependency theory (as they once were in PS theory) because they disrupt the normally simple relationship among dependencies, phrases and linear order. If we assume that all the words which depend (directly or indirectly) on a single word constitute a phrase, it remains true that phrases are normally continuous, i.e. not interrupted. Normally an infringement of this generalization leads to ungrammaticality. For example, what happens if we combine the following entries? (16)-a after -c N P (17) parties N [pl] (18)big a- N A The ordering restrictions on after and big require parties to follow both these words, but nothing in the entries restricts the relative order of after and big; and yet after big parties is fine while *big after parties (with big depending on parties) is totally ungrammatical. The obvious explanation is that big parties is a phrase, so it must be continuous - i.e. it must not be split by a word, such as with, which is not part of the phrase. Traditionally PS-based theories have assumed that phrases should be equivalent to a bracketing of the string of words, which means that discontinuous phrases are ruled out a priori as a fundamental impossibility - a discontinuous phrase simply cannot be separated by brackets from the rest of the sentence, because any brackets round the whole phrase must also include the interruption. Admittedly alternative views of PS have been proposed in which discontinuity is possible (McCawley 1982), and indeed the same is true of any PS-based theory (such as HPSG) which admits structure sharing. But if discontinuous structures are admitted in principle, what then excludes strings like *big after parties? The question seems trivially easy to answer from an HPSG perspective: discontinuity is only permitted when it is caused by structure sharing, and structure sharing is only permitted when it is explicitly sanctioned in the grammar. Structure sharing removes a single element from one constituent and makes it act as part of another (higher) constituent. For example, subject-raising causes discontinuity by locating the lower clause's subject in a named place (subject) in the higher clause; but since the grammar says this structure sharing is ok, it is ok. In contrast, there is no structure sharing pattern which allows big to move away from parties, so discontinuity is not ok. What will turn out to be a weakness in this answer is that the grammar has to stipulate each structure sharing possibility. In most cases this is no problem but the problem data that we consider below will show that more flexibility is needed. There is an alternative which is much more obviously compatible with DS than with PS, and which will play a crucial part in the later discussion; so to the extent that the explanation works it will count as evidence against PS. The alternative is to ask what the essential difference is between the structures of It stopped raining, where the discontinuous phrase it ... raining is grammatical, and of *big after parties, with the illegal *big ... parties - apart from the fact that one is allowed and the other isn't. The difference is that all the words in It stopped raining are held together by one continuous phrase (the whole sentence). It has a legitimate place in the sentence thanks to its dependency on stopped, whereas the only link between big and the rest of the sentence lies through the discontinuous phrase. In other words, the grammatical sentence has a substructure which is free of discontinuities but holds all the words together. This observation provides the basis for a very general principle which controls discontinuity in DS. For rather obvious reasons discontinuity always results in tangling arrows (provided we consider the vertical arrow above the sentence root to be infinitely long). The No-tangling Principle A string of words is not grammatical unless its dependency structure includes a substructure in which: a. there is a single `root' word, b. every other word depends either directly or indirectly on the root, c. for each word, there is a single, minimal, chain of dependencies to the root, d. no dependencies tangle. We can call this tangle-free substructure the phrase's `surface structure' because this is the structure which is responsible for surface word-order. The only clause that needs any comment is (c). The point of this requirement is to force `raising' while excluding `lowering'; so if a word has two anchors, one nearer to the root than the other, the one to be included in the substructure must be the former. For example, the verb stop shares its subject with its participle complement, but clause (c) guarantees that this shared word is treated in surface structure as the subject of stop, not of the complement. This means that there is no need to build this asymmetry into the lexical entry for stop, and indeed in true WG notation (in contrast with the compromise used in 0) the entry is neutral regarding word order. The relevant WG information on stop is actually a proposition2 which is equally compatible with 2Strictly speaking this proposition is in turn derived, by inheritance, from a simpler proposition about stop plus a general proposition about the dependency-type `xcomp' (named after its counterpart in LFG). (i) stop has an xcomp. (ii) A verb's subject is also the subject of its xcomp. either position for the shared subject: (19)The subject of stop is also the subject of its complement. In contrast, the HPSG analysis builds the raising into each relevant lexical entry and structure-description, as a stipulation rather than as a general principle. The No-tangling Principle will be crucial to the arguments in the rest of the paper. It expresses a putative universal of syntax which limits the kinds of discontinuity that are permitted in any language; but it also removes the need to stipulate how structure sharing affects surface word order. This means, on the one hand, that we can simplify lexical entries as in 0, but much more importantly it provides flexibility at just the points where it is needed. It will allow us to solve one of our problems by providing two alternative surface structures for certain rather special dependency structures; and the other problem will be solved by allowing an indefinite number of raising slots controlled only by one general rule plus the No-tangling Principle. In diagrams it is convenient to separate the surface structure from the other dependencies by drawing it above the words (literally `on the surface', if the word-string defines `ground level'), with all other dependencies added below. With this change the structure for It has stopped raining is shown in Fig. 6. 6 Fig. 6 The effect of the No-tangling Principle is to guarantee that any example of discontinuity must also involve structure sharing (with the possible exception of discontinuities caused by parenthetical elements such as vocatives, which we shall simply ignore here). The converse does not apply: not all examples of structure sharing lead to discontinuity. For example, both WG and HPSG treat so-called `Exceptional Case-Marking' verbs as subject-to-object raisers, so the lower verb's subject is also the higher verb's object, but this does not in itself lead to discontinuity as can be seen from the structure in Fig. 7 for John expected Mary to come. Proposition (ii) is a default which is overridden when the verb has an object: (iii)A transitive verb's object is also the subject of its xcomp. 7 Fig. 7 To prepare for the next section we need to illustrate two other kinds of discontinuous structure: extraction, and extraposition from NP. The grammar entries responsible for extraction are shown in 0, using the HPSG terminology for the three entries (Pollard & Sag 1994: 160). The `Top' entry optionally allows any word to be attached to a finite verb (i.e. a tensed verb or an imperative) by the dependency labelled `x+' (short for `extractee', but distinguished from `+x' for `extraposee' by the `+' which marks the relative position of the anchor; in Hudson (1990) this dependency is called `visitor'). This is the entry for topicalisation, as in Beans I like, and other Top entries are needed for other types of extraction such as relative clauses and tough-movement. The `Middle' entry allows the extractee of one word to be passed recursively down a chain of dependents, and the `Bottom' entry allows the extractee dependency to be `cashed' for some kind of complement relationship. Without this final trade-in the extractee has no semantic role in the sentence, so extraction is impossible. Fig. 8 shows a sample structure in which all three entries have applied. (20) Extraction: a. `Top' word x+- V [fin] 8 b. `Middle' word x+- word -c word __ x+ __/ c. `Bottom' word x+,c- word Fig. 8 Fig. 8 shows two discontinuous phrases, beans ... that you like and beans ... you like, both of which are justified by the structure sharing of the `Middle' entry. Why does the `extractee' relation override the word-order demands of the object dependency? In this case the explanation involves default inheritance. In WG generalisations about dependencies as well as those about word-classes apply only by default, i.e. unless overridden by more specific requirements. As we shall see in section 6, dependencies, like word-classes, are organised in an inheritance hierarchy with `dependent' as the most general type and more specific types such as `subject' and `complement' below it. The word-order rule which applies to objects is actually just one application of the very general anchor-first default rule for English. The rule which positions extractees before their anchors is more specific, applying just to extractees3. (21)General: A word follows its anchor. Extractees only: An extractee precedes its anchor. The general principle of default inheritance ensures that the latter overrides the former. Extraposition from NP is somewhat simpler as it involves only a single, non-recursive, entry which generates examples like the following: (22) Reports have emerged of widespread atrocities. Someone came to see me who I hadn't seen for years. (23) Extraposition from NP: V -+x word / N _/ In this entry4 the vertical dependency arrow from V to N means that the N concerned may either 3In Hudson 1990 I argued for a basic division of English dependencies into `predependent' and `postdependent', with `extractee' (alias `visitor') as a type of predependent. In that analysis the word-order rule for extractees is in fact the one for predependents in general. This is a side issue which is not relevant to the present discussion. 4The entry given here ignores what may turn out to be a serious problem for the WG analysis of determiners as heads: an intervening determiner does not affect extraposability, in contrast with other intervening material which does. For example, (ii) is just as good as (i) in spite of the determiner some which (according to WG) adds an extra dependency between reports and are. (i) Reports have emerged of widespread atrocities. (ii) Some reports have emerged of widespread atrocities. In contrast, indisputable extra dependencies can make extraposition harder (the so-called `Right-Roof Effect'), as in (iv) contrasting with (iii). precede or follow the `pivot' verb. This verb accepts one of the N's dependents as its own `extraposee', labelled `+x'; more specifically, it accepts one of the N's `post-dependents' (i.e. one of its complements or post-anchor adjuncts). Fig. 9 shows the structure generated for the first example. 9 Fig. 9 Why does the structure sharing have the effect of moving the extraposee away from its first anchor? Because raising is obligatory, so in the surface structure what counts is its extraposee relation to the V, rather than its adjunct relation to the N. The most important point to emerge from this discussion of structure sharing and discontinuity in WG is that the consequences of structure sharing for word order are due to the No-tangling Principle rather than to stipulated entries. We are now ready to consider our two main empirical problems. 4. Preposed adverbials in English wh-questions Adverbials (adjuncts of place, time, cause, etc.) can generally be preposed, giving examples like the following which I take to be straightforwardly grammatical. The preposed adverbial phrases are bracketed. (24)[After that] I saw Mary. [When he calls] tell him to ring back. [For supper] we had ice-cream. (iii) Reports of atrocities have emerged that have been denied. (iv) ?Reports of atrocities have emerged that were committed by government forces. On the other hand it is possible that the constraint is due to processing difficulties. This might explain the relative goodness of examples like (v), where the intervening structure is semantically rather `bland'. (v) A collection of reports has been published of widespread atrocities. If there is a processing explanation, then the entry for Extraposition should allow the `source' noun to depend only indirectly on the pivot verb. This preposing involves the same extraction process which we illustrated above, but the exact mechanics are irrelevant. The main point is that the adverbial is a dependent of the first verb. The structure for the last example is in Fig. 10, with the adverbial shown simply as `a' (for `adjunct') of the verb. 10 Fig. 10 Adverbial preposing seems to apply freely to wh-interrogative sentences as well, as shown by the following examples. (25) [After that] who did you see? [When he calls] what shall I say to him? [For supper] who had ice-cream? Only one order is possible: preposed adverbial followed by wh-pronoun. (26) *Who [after that] did you see? *What [when he calls] shall I say to him? *Who [for supper] had ice-cream? In fact, the preposed adverbial is in general the very first element in any sentence, as it also has to precede the uninverted subjects in 0. In a DS analysis there is no reason to doubt that the preposed adverb and the wh-pronoun are both dependents of the first verb, as shown in Fig. 11. 11 Fig. 11 The most natural PS analysis would presumably treat the adverbial as an adjunct of the rest of the sentence, as in Fig. 12. 12 Fig. 12 The crucial point about this structure is that whatever the label on the top node may be, adjunction guarantees that it is identical to the one on the lower `sentence' node. Whichever kind of analysis we use, then, there is no reason why the fronted adverbial should affect the distribution of the whole clause. Now we come to the problem. In the dependency analysis in Fig. 11, the root of the sentence is clearly the tensed verb, had, and the two preceding elements, the adverbial and the wh-pronoun, are simply dependents. We should therefore expect to be able to use the sentence as a subordinate clause in a larger sentence such as 0. (27) *For supper who had ice-cream is unclear. (compare: Who had ice-cream for supper is unclear.) But this is ungrammatical, although the corresponding sentence with the adverbial un-fronted is fine. The same is true more generally of all our examples when embedded as subordinate clauses. (28) *I wonder [after that] who you saw. *I wonder [when he calls] what I should say to him. *I wonder [for supper] who had ice-cream. Why? It is easy to describe the problem informally: the wh-pronoun marks the absolute beginning of the subordinate clause, in much the same way as a subordinator such as that, so the above examples are bad for just the same reason as the following: (29)*I know [after that] that you saw Mary. *I know [when he calls] that I should tell him to ring back. *I know [for supper] that we had ice-cream. These sentences can all be mended, of course, by reversing the order of that and the adverbial, which shows that adverbial fronting is possible in subordinate clauses (thus eliminating a pragmatic explanation along the lines that fronting is pragmatically allowed only in main clauses): (30)I know that [after that] you saw Mary. I know that [when he calls] I should tell him to ring back. I know that [for supper] we had ice-cream. But if the wh-pronoun blocks pre-posing in the subordinate clause, why not in the main clause as well? And why can't we mend the subordinate questions in the same way as the that clauses, simply by reversing the order of the wh-pronoun and the adverbial? (31)*I wonder who [after that] you saw. *I wonder what [when he calls] I should say to him. *I wonder who [for supper] had ice-cream. For those attracted by a GB-style analysis, it is worth pointing out the problems raised by the data just cited5. If the wh-pronoun was positioned before the `Comp' position of that, then a wh-pronoun ought to be able to replace that before a preposed adverbial; so why is this not possible 0? Similarly, if the preposed adverb was adjoined to CP and the wh-pronoun was moved to the specifier of Comp, the combination adverbial + wh-pronoun should be just as possible in a subordinate clause as in a main clause; but it is not 0. (It should be noticed, incidentally, that the interrogative clause need not be a complement, as witness 0, so the solution does not lie in the general ban on adjunction to complements suggested in Chomsky (1986: 6).) The WG explanation requires a discussion of the structure of wh-questions. Take a very simple example like Who came? Which word depends on the other? In the last paragraph we took the verb to be the root of this sentence as in virtually every other sentence. The centrality of the verb is one of the main tenets not only of dependency analysis but of virtually every other modern analysis (including HPSG, in which a sentence is a kind of VP). After all, if who is the subject of came, and subjects are dependents, then who certainly depends on came. But there is also another set of facts about wh-questions which support the opposite analysis, with the verb depending on the wh-pronoun (Hudson 1990:362ff): The verb (and therefore the rest of the clause) can be omitted, leaving just the wh-pronoun (`sluicing'); e.g. I know someone came, but I don't know who. The wh-pronoun is the link between the clause and a higher verb; for example, wonder subcategorizes for an interrogative clause, which means a clause introduced by an `interrogative word' - a wh-pronoun, whether or if. In DS terms this means that in I wonder who came, who depends on wonder, and came on who. It would be extremely difficult to write the necessary rules if came depended directly on wonder: `a tensed verb which depends on wonder must itself have a dependent interrogative word in first position'. The wh-pronoun seems to select the form of the following verb. After most pronouns this may be either a tensed verb or TO plus infinitive, but one word is different: after why only a tensed verb is permitted. (Compare I was wondering when/why we should do it with I was wondering when/*why to do it.) Selection of this kind is typical of anchors in relation to complements, which again suggests that the verb depends on the wh-pronoun. Semantically the verb (on behalf of the rest of the clause) modifies the wh-pronoun in much the same way as a relative clause. For example, the question Who came? is asking for the identity of the person that came, where that came clearly modifies person. 5These facts are among the evidence against the existence of the categories `Comp' and `complementizer' in Hudson 1995b. In short, there is at least a good prima facie case for taking who as the anchor of came in Who came?. This descriptive conclusion is supported by similar conclusions from relative clauses and possibly other areas of grammar as well, and leads to a very important theoretical conclusion: that mutual dependency is possible. There are good reasons for taking who as a dependent of came, but there are equally good reasons for taking came as a dependent of who. At this point DS and PS part company severely. Although DS theory has traditionally set its face against mutual dependence, this is just a matter of theoretical stipulation and could be abandoned under pressure. For PS, as far as I can see, it is impossible to show mutual dependence in a monostratal system, and even a transformational analysis would face severe problems. It remains to be seen whether this pessimistic conclusion about PS is justified. How does all this help with our problem? Because mutual dependency interacts with the No-tangling Principle to give a free choice of surface structure. Either of the dependencies in Who came? will satisfy the Principle, so either could be the (entire) surface structure. Thus there are two ways in which we could draw the structure for Who came?, both shown in Fig. 13. 13 Fig. 13 This choice is not a syntactic ambiguity, but two alternative ways of satisfying the No-tangling Principle. In this respect the diagramming system is misleading, so it should be remembered that there is just a single syntactic structure for each sentence, in which each `surface structure' is simply a sub-structure which satisfies the No-tangling Principle. We now return to the examples with fronted adverbials. Take the sentence [For supper] who had ice-cream? Which word is its root (i.e. the word on which the rest of the sentence depends) - who or had? Fig. 11 took had as the root, which is the only correct answer. In this case who is not a possible sentence-root because its arrow would tangle with the one linking for supper to had, as can be seen from Fig. 14 which shows the choice which is now offered by the mutual dependency of who and had. 14 Fig. 14 For the embedded example, however, even this option is impossible because who has to be taken as the root of the subordinate clause. Fig. 15 shows the only possible structure for an example without the offending adverbial, where the main point is the dependency between wonder and who. 15 Fig. 15 Given this dependency, there is no way to avoid the tangling caused by the fronted adverbial, which can be seen in Fig. 16. 16 Fig. 16 To summarise the argument, in who had ice-cream there are two ways to satisfy the No-tangling Principle because both who and had make acceptable sentence-roots. If we add a fronted adverbial such as for supper, this precludes who as a root; and embedding the clause precludes had as root. It follows that if we combine the two patterns, neither word qualifies as a possible root and the structure collapses completely. Hence the ungrammaticality of *I wonder for supper who had ice-cream. 5. Partial verb-phrases in German and Dutch The second empirical problem which will show the advantages of PS-free analysis is that German and Dutch both allow movement of a `partial VP'. This phenomenon has received a good deal of attention, especially within the HPSG community (e.g. Baker 1994, Haider 1990, Johnson 1986, Nerbonne 1994, Uszkoreit 1987a, b, van Noord & Bouma 1995). Native speakers seem to agree that German examples like the following (from Uszkoreit 1987a) are grammatical: (32)[Den Brief zustecken] sollte der Kurier nachher einem Spion. [the letter to-slip] was the courier afterwards to-a spy. `The courier was to slip the letter afterwards to a spy.' The problem is that on the one hand there is solid evidence that the bracketed material forms a single phrase (because German grammar requires the finite verb, in this case sollte, to follow just a single constituent), but on the other hand this would be less than a complete phrase in any standard analysis of the un-fronted equivalent 0. (33) Der Kurier sollte nachher einem Spion den Brief zustecken. The courier was afterwards to-a spy the letter slip. The facts are fairly simple. German allows the finite verb to follow any one of its own dependents: (34) Er isst einen Apfel jeden Tag. He eats an apple every day. Einen Apfel isst er jeden Tag. Jeden Tag isst er einen Apfel. If the finite verb is an auxiliary such as sollte in the earlier examples, the element before it may be a dependent of the auxiliary's complement infinitive: (35)Er sollte einen Apfel jeden Tag essen. He was an apple every day to-eat. Einen Apfel sollte er jeden Tag essen. Jeden Tag sollte er einen Apfel essen. In each case the first element is an entire phrase; in general, phrases must be kept intact (as in every other language). The exception to this generalisation is that putative verb-phrases, called `partial VPs', may be fronted as illustrated in 0 above, as well as in the following further permutations of the same elements: (36) [Zustecken] sollte der Kurier nachher den Brief einem Spion. [Einem Spion zustecken] sollte der Kurier nachher den Brief. [Nachher einem Spion zustecken] sollte der Kurier den Brief. It is even possible for the syntactic subject to be included in the front-shifted group of words, though this is only possible for very `inactive' subjects: (37)[Ein wirklicher Fehler unterlaufen] war ihm noch nie. A real error happened was to-him yet never `He had never yet made a real error.' (38)[Eine Concorde gelandet] ist hier noch nie.6 A Concord landed is here yet never. (39) [Ein Witz erzählt] wurde.7 A joke told was. (40) [Ein solch schönes Geschenk gemacht] wurde mir noch nie. A so beautiful present made was to-me yet never. In spite of the arguments in Baker (1994) it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the first phrase in each of the bracketed groups really is the subject of both the verbs. Most obviously, it is in the nominative case, which is normally found only in clear subjects (or predicative nominals). Slightly more subtly, the last two examples have passive participles (erzählt, gemacht), which is evidence that the nominative phrases have been raised from object to subject, and are therefore subjects (Müller 1995). Similar patterns are found in Dutch. The following examples are from van Noord & Bouma 1995. (41)[Bezocht] heeft Jan dat congres nog nooit. visited has Jan that conference still never. (42)[Bezoeken] to-visit zou Jan dat congres niet willen. would Jan that conference not want. (43)[Bezoeken willen] heeft Jan dat congres nooit. to-visit wanted has Jan that conference never. The last example is particularly significant, illustrating as it does the recursive power of the process behind the fronting. We shall return to it later but meanwhile we shall concentrate on German. These structures are a serious challenge for most theories of syntactic structure because the fronted groups do not correspond to phrases that are recognised in the structure of a sentence whose subordinate verb is in its normal position at the end of the sentence. In other words, they involve movement of non-constituents. To take a simple example given earlier 0, it is possible to front-shift essen, `to eat', along with any combination of einen Apfel, `an apple' and jeden Tag, `every day'. 6Example 7This from Andreas Kathol, via HPSG network. example and the next are from Müller 1995. (44)[Essen] sollte er jeden Tag einen Apfel. [Einen Apfel essen] sollte er jeden Tag. [Jeden Tag essen] sollte er einen Apfel. [Jeden Tag einen Apfel essen] sollte er. Admittedly German word order is sufficiently free for each fronted group to be able to constitute the tail of a `normal' clause, but there is no evidence at all that they constitute a constituent when they do. Moreover, to assume such phrases would be to abandon the idea that a verb and its object form a phrase which excludes adjuncts; for example it would oblige us to recognise a `verb-phrase' consisting of jeden Tag, a clear adjunct, and essen, but excluding the latter's object einen Apfel: ... einen Apfel [jeden Tag essen]. Suitable grammars can be constructed (as Uszkoreit 1987a demonstrates), but at great theoretical cost and with few descriptive insights. Turning to DS-based analyses, if anything the challenge is even more serious for conventional DS accounts than for PS-based ones, because the object and adjunct depend on the infinitive but need not move with it, contrary to basic tenets of dependency grammar. The problem can be seen in Fig. 17, a conventional DS analysis of Er sollte jeden Tag einen Apfel essen, `He should eat an apple every day'. 17 Fig. 17 If essen is fronted, then it should take all its dependents with it because the alternative is either for them to be left without anchors, or for the dependencies to tangle with others; and in either case the No-tangling Principle is broken. These alternatives are illustrated in Fig. 18 for Essen sollte er jeden Tag einen Apfel. 18 Fig. 18 Whereas the PS problem was that the fronted `phrases' implied a very clumsy and unrevealing analysis of ordinary clauses, the DS problem is that a fronted verb which leaves its dependents behind is simply impossible to analyse. One way to solve these problems is to assume a flat, VP-less structure (which is no problem for HPSG, and obligatory in any case for WG), plus optional raising dependencies controlled by the No-tangling Principle. First, however, we must provide a little background grammar for German. The verb-second phenomenon is easy to handle if we assume that each (non-interrogative) finite verb has just one `extractee', again labelled `x+', which must be combined with one dependent of that verb, or (recursively) of any non-finite verb which depends on it. (In many German dialects extraction is limited to non-finite clauses.) For example, in Einen Apfel isst er jeden Tag, `An apple eats he every day', einen (Apfel) is both the extractee and the object of isst; and similarly for Einen Apfel sollte er jeden Tag essen, where einen is extractee of both sollte and essen, as well as the latter's object. The structure is in Fig. 19. 19 Fig. 19 With extractees as an exception, a sentence-root verb precedes all its dependents; but this order is reversed for other verbs - i.e. for any verbs which depend on another word. (45)German/Dutch word order rules: A sentence root precedes all its dependents. Other verbs follow their dependents. For example, in the last example the sentence-root verb sollte has three dependents: einen Apfel (which as extractee precedes it), er and essen, both of which follow it; but essen follows both of its un-extracted dependents, er and jeden (Tag). Suppose we now, following Baker 1994, apply a `universal raising' rule to the extracted verbal complement of any auxiliary verbs. This would raise any number of dependents of the complement verb to serve also as a dependent of the higher auxiliary verb. Since raising is obligatory, these dependents of the lower verb will be positioned as though dependents of the higher verb, while their unraised co-dependents stick to the lower verb. This pattern involves a new kind of raising. It is clearly not raising to subject, extraction or extraposition (the three types of raising discussed so far), so we must invent a new name for the relationship which is involved. The obvious name is `raisee', which we shall adopt with the abbreviation `r'. (46) German/Dutch universal raising Any number of dependents of an extracted verbal complement of an auxiliary verb A may also be raisees of A. This raising option is only available for a very restricted range of sentences, and does not lead to ambiguity. It applies only to verbs which are both complements of an auxiliary verb and also extracted, and when a dependent receives the extra `raisee' dependency this affects its position in the sentence. For example, if essen depends on the auxiliary sollte, then at one extreme we can raise every single dependent into the surface structure so that they take their position after sollte: Essen sollte er jeden Tag einen Apfel. At the other extreme, there could be no raisees at all so all the words concerned line up before essen: Jeden Tag einen Apfel essen sollte er. And in between we could raise, say, jeden Tag but not einen Apfel: Einen Apfel essen sollte er jeden Tag. Structures for the three variants on our simple example are shown in Fig. 20 to 22. 20 Fig. 20 21 Fig. 21 22 Fig. 22 What about subjects that are front-shifted with the infinitive, as in 0 to 0? These are surprising because one would expect them to be covered by ordinary subject-raising, which ought to apply obligatorily. If Ein (Fehler), `an error', in 0 is the subject of the infinitive unterlaufen, and if war is an auxiliary (as it obviously is), then the link between Ein Fehler and war ought to be in the surface structure instead of the lower subject link. The solution must be more tentative, but it is possible that this pattern is linked to the fact that German tensed verbs, unlike English ones, do not have to have a subject. In the following classic examples there is no subject. (47) Mich friert. `Me freezes', i.e. `I am cold' Jetzt wird gearbeitet. `Now is worked', i.e. `Let's get down to work now' If the subject slot is optional for the auxiliary verb, then raising to it must also be optional. In that case, the problem disappears as the infinitive's subject has no dependency link to the main clause. This analysis may also help to explain why the unraised subject must be inactive; subjectless sentences seem only to be possible with inactive verbs (such as frieren) and passives. As stated, the German Universal raising rule predicts that raising applies recursively across auxiliary verbs. This may be true for German, but it is certainly true for Dutch to judge by the example quoted earlier 0 and repeated here: (48)[Bezoeken willen] heeft Jan dat congres nooit. to-visit wanted has Jan that conference never. In this example one auxiliary (willen) depends on another (heeft), so any dependent of willen may qualify also as a raisee of heeft, including dependents which are merely raisees of willen. This applies specifically to dat (congres), which must be a raisee of heeft as well as raiseee of willen and object of bezoeken. Van Noord & Bouma (1995) show that the partial VP fronting which we have been discussing is closely related to another construction found in Dutch and in some dialects of German: cross-serial dependencies among final verbs. The facts are well known and much discussed since Bresnan et al (1983). The following examples are from Van Noord & Bouma 1995. (49)... dat Jan het boek wil lezen. ... that Jan the book wants to-read. (50) ... dat Jan Marie het boek laat lezen. `that Jan lets Mary read the book' (51)... dat Jan Marie het boek wil laten lezen. `that Jan wants to-let Mary read the book. The examples are challenging because the verbs occur in the same order as their dependents, which inevitably leads to tangling (`cross-serial') dependencies. However, universal raising may offer a solution here as well. Let's assume that the dependent verbs are delayed by extraposition; e.g. in 0 lezen could have preceded wil but is extraposed instead. This is an extra `raising' dependency, labelled `+x', which allows us to define another class of verbs that depend on auxiliaries. If universal raising were to apply to these verbs as well, any of their dependents could become raisees of the auxiliary, which would avoid tangling in surface structure as shown in Figs. 23 to 25. 23 Fig. 23 24 Fig. 24 25 Fig. 25 It should be noticed that universal raising simply provides a background to other rules, and in particular for the rules which allow verb extraposition. This explains why standard German does not allow such examples, although it does have universal raising. The details of the rules are a separate topic which is only indirectly relevant here. The main point is that a small extension of Universal Raising may cover this construction as well. Moreover, this extension involves what looks like a rather natural class of dependents, extractee and extraposee. (52)German/Dutch universal raising (extended) Any number of dependents of an extracted or extraposed verbal complement of an auxiliary verb A may also be raisees of A. This section has suggested that Dutch and German share the rule of Universal Raising, which interacts with the No-tangling Principle to explain not only why `partial verb-phrases' can be fronted but also why the expected order of verbs in final clusters can be reversed without producing dependency chaos. The analysis relied crucially on the absence of any predetermined raising structure, and more generally of any predetermined PS; raisee relationships are added freely to the ordinary DS, generating patterns which are otherwise not possible. It is hard to see how this kind of flexibility could be provided by a PS-based analysis which required a separate entry for each structure-sharing pattern. The price we have paid for the explanation is the introduction of a new dependency, `raisee', whose sole function is to give extra flexibility in word order. Knowing that one word is the raisee of another tells us nothing at all about the semantic relationship between them - indeed it almost guarantees the absence of such a relationship; nor does it `carry' any other syntactic rules, such as agreement or selection. This emptiness distinguishes the raisee dependency from most others, but it is not unique. The next section takes this classification of dependencies a little further. 6. Dependencies and binding One of the general themes running through this paper has been that structure sharing is the correct way to handle departures from basic syntax. On this WG and HPSG are agreed. However one rather fundamental point of difference is over the treatment of dependency categories, the named attributes whose values may be words or phrases. HPSG has no unifying concept or slot which covers them all - complements are in SUBCAT, subjects in SUBJ, and adjuncts in ADJUNCT. In contrast, for WG they are all instances of the category `dependent' which may be further subdivided into more or less general subcategories such as `complement' (divided further into `object', `indirect object', and so on). This hierarchical classification of dependencies not only allows generalisations across them, but encourages one to look for similarities and differences among specific dependency types, so we can now survey the dependencies which we have mentioned in this paper. Do any broad generalisations emerge about any cluster of dependencies? The examples of structure sharing have involved only a small number of dependency types: subject, extractee, extraposee and raisee. These fall into two groups. Subject can be used without any structure sharing (e.g. in any simple single-verb sentence), but the other three are never used except in structure sharing. An extractee is never just an extractee, because this does not give enough information to integrate the word into the sentence's semantic structure; it also has to bear some `proper' dependency relation such as object. Similarly for extraposees and raisees. Subjects are not alone in being able to occur either with or without structure sharing (i.e. subject raising); if a subject-to-object raising analysis is right, then the same is also true at least of objects. For most dependency types, however, structure sharing may not be possible, so we seem to have the basis at least for a broad two-way classification of dependencies according to whether or not sharing is their sole function. We shall arrive at an important generalisation about binding in which PS plays no part at all, and indeed in which any notion of PS would simply get in the way. Before we approach binding we can review the distinctive features of these three dependency types which we have already discussed. As just mentioned, they are always involved in structure sharing. They are always `raisers' - i.e. when they combine with some other dependency type, they are always the higher of the two. Therefore they are always part of surface structure (except when used recursively, in which case the `lower' dependencies are excluded from surface structure). They never combine with each other, but only with dependencies of the other type (e.g. an extractee of one word may also, recursively, be an extractee of another word, but it cannot be a raisee of another word; in contrast, the subject of one word may be the object of another word). In recognition of these similarities we can call extractees, extraposees and raisees `s-links', where the `s-' recalls the s's of `surface structure' and `structure sharing'. As van Noord & Bouma (1995) point out, the s-links extractee and raisee are irrelevant to binding. (The same may be true of extraposition, but it is hard to construct critical examples.) The following Dutch examples are from van Noord & Bouma's paper: (53)dat Jani Pietj zichzelfj/*i ziet wassen `that Jani sees Pietj wash himselfj/*i' The binding possibilities are exactly the same in the Dutch example as in its English translation, but in the Dutch example this is surprising given the dependency structures argued for above. Universal raising has raised zichzelf into the top clause, as raisee of ziet, so it is a co-dependent of Jan. In general a reflexive pronoun can be bound by the subject of its clause; in DS terms, it can be bound by a co-dependent subject (Hudson 1984:173ff). Why then can't Piet bind zichzelf in this example? Because the raisee dependency is invisible to binding. The next example confirms this conclusion. (54) dat Jani Pietj hemi/*j ziet wassen `that Jani sees Pietj wash himi/*j' Once again the raisee link between hem and ziet must be invisible to binding, because otherwise hem would count as a co-dependent of Jan and should be non-coreferential, as it is for Piet. The same is true for the extractee relationship in English as can be seen from the following (rather stilted) examples. (55)Himself/me/*him/*myself I think John admires. The possibilities are exactly the same as in the un-extracted version: (56)I think John admires himself/me/*him/*myself. And yet there is no reason to doubt the existence of the extractee dependency between the pronoun and think in 0, which makes the pronoun into a co-dependent of I. The only possible conclusion is that this dependency, like the raisee one, is invisible to binding. According to van Noord and Bouma, a recent development in HPSG theory (Iida et al 1994) would have two separate lists of dependents: SUBCAT, for all complements, and ARG-S (`argument-structure') just for those that are visible to binding. To make the contrast in this way is to shift the explanatory focus away from tree geometry (and PS) to the classification of the relationships themselves (and DS). Similarly, WG dependencies, as mentioned earlier, are organised in an inheritance hierarchy from `dependent' at the top to specific grammatical relations like `subject' and `object' at the bottom. This allows us to make the same distinction as in HPSG, but to incorporate it into the overall classification of dependencies. Fig. 27 presents a revised version of the dependency system in Hudson (1990: 208). Dependents are of two kinds: s-links (explained above) and b-links, with b- to remind us that they are visible to binding, that they are basic and that they are the bottom relationship in a structure sharing pattern. This distinction is presumably universal, though there may be some languages which have no s-links at all. (After all, `raisee' is part of German and Dutch but not of English, and Japanese seems not to have any extraction.) A very different contrast applies to languages with `mixed' word order (where head-final constructions exist alongside head-initial ones). These seem to need a general distinction between `pre-dependent' and `post-dependent' (respectively, dependents that precede and follow their anchor). In Fig. 26, unlike Hudson (1990), this distinction is separate from the main system. This diagram needs a little more explanation. The convention for showing inheritance (or `isa') relations is also new (Hudson 1995c): a triangle has its (large) base against the larger, more general, category, and its (small) apex linked to the subcategories or members. The diagram thus allows multiple inheritance for dependencies; e.g. `subject' inherits both from `valent' and from `pre-dependent'. The dotted lines apply to English but probably not to German and Dutch (where relative order of verb complements is generally controlled by the German/Dutch word order rules in 0); and `raisee' is bracketed because it is part of German and Dutch but not English. 26 Fig. 26 The b-link/s-link distinction is similar to that between A- (`argument') and A'-positions in GB, but does not involve tree-geometry and PS at all. Like the HPSG analysis of binding in terms of obliqueness, it shows that not only can non-PS analyses `work', but they can also be expressed in terms of natural and possibly universal categories. 7. Conclusions A reasonable conclusion is that PS does not help to solve some of the most interesting problems, and indeed probably makes them even harder to solve; as I put it earlier, the PS is part of the problem, not of the solution. This case is particularly easy to argue when a lot of dependency apparatus is already available and transformational solutions are unavailable, as in HPSG. The main evidence for this conclusion involved our two empirical problems: The interaction between adverb-preposing, wh-movement and clause subordination in English is quite easy to explain in terms of DS. The explanation hinged crucially on the assumption that the wh-pronoun and the clause's root verb are mutually dependent, which would be difficult if not impossible to express in a PS analysis. `Partial verb phrases' in German and Dutch are problematic for a PS analysis because they involve phrases for which there is otherwise no evidence, and which in fact make normal structures much harder to analyse. For a DS analysis all we need is a new relationship `raisee' which can be added freely to any dependent just in those environments where partial VPs occur. However, we also considered some other supporting evidence: Many lexical or grammatical facts involve restrictions imposed by one word on the head-word in an accompanying phrase; e.g. a word may select a PP with a specific preposition, a VP whose verb has a particular inflection, and so on. In these cases the particularities of the head-word itself are directly visible to the controlling word in a DS analysis but not in a PS analysis, where they have to be projected up onto the phrase node. This can be done, but the PS is the cause of the problem. The peculiarities of s-links are hard to express in terms of PS, especially when they include the German/Dutch `raisee' links but not subjects; at best PS is a harmless irrelevance. If dependencies are available, they can be classified with `s-link' as one important subclass which can be mentioned, as appropriate, in generalisations about raising, surface structure and binding. What are the implications of this conclusion for syntactic theory in general, and for HPSG in particular? It is hard to draw general conclusions beyond a plea for the issue to be given the attention it deserves. For most syntacticians the need for PS is one of the few things that they are really sure of, and which they might well describe as one of the pillars of modern syntactic theory. As I have already observed, most modern syntacticians also accept a lot of dependency-based concepts which were not recognised in the early days of PS theory, so it is high time for a general review of the evidence for PS. As far as HPSG is concerned, however, the conclusion is simple: the theory no longer needs PS. Apart from the theory's name (why not HG?), the main thing which requires attention is the `official' notation, where boxes-within-boxes can give way to boxes-beside-boxes. For example, to return to the elementary example Kim gives Sandy Fido, instead of the HPSG analysis with VP and S boxes to hold the word and phrase boxes together we could have the following, which in every other respect preserves the insights of the HPSG analysis. 27 Fig. 27 The cross-referencing between boxes could be made more visible by adding dependency arcs, but that really is just a matter of notation. Apart from these notational changes, the main change needed in the theory is a revised `subcategorization principle' (Pollard & Sag 1994:34). As it stands this principle reads as follows: (57)SUBCATEGORIZATION PRINCIPLE (ORIGINAL VERSION) In a headed phrase (i.e. a phrasal sign whose DTRS value is of sort head-struc), the SUBCAT value of the head daughter is the concatenation of the phrase's SUBCAT list with the list (in order of increasing obliqueness) of SYNSEM values of the complement daughters. Without PS sisters (i.e. accompanying words) take over the role of the daughters: (58) SUBCATEGORIZATION PRINCIPLE (REVISED VERSION) The SUBCAT value of any word is a list (in order of increasing obliqueness) containing the SYNSEM values of some of its sister words. Various other revisions could also be considered but the main point that emerges from this paper is that PS could be removed from current HPSG with considerable gains and little, if any, loss. References Baker, Kathryn. 1994. An extended account of `modal flip' and partial verb phrase fronting in German = CMU-LCL-94-4. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, Laboratory for Computational Linguistics. Bresnan, Joan; Kaplan, Ronald; Peters, Stan; & Zaenen, Annie. 1983. Cross-serial dependencies in Dutch. Linguistic Inquiry, 13: 613-35. Chomsky, N. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Fraser, Norman & Hudson, Richard. 1992. Inheritance in Word Grammar. Computational Linguistics 18: 133-59. Haider, Hubert. 1990. Topicalization and other puzzles of German syntax. In Gunther Grewendorff, & Wolfgang Sternefeld (eds.) Scrambling and Barriers. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 43-112. Hudson, Richard. 1984. Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Hudson, Richard. 1990. English Word Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Hudson, Richard. 1992. Raising in syntax, semantics and cognition. In Iggy Roca, ed. Thematic Structure: Its role in grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 175-98. Hudson, Richard. 1993. Do we have heads in our minds? In Greville Corbett, Scott McGlashan & Norman Fraser, eds. Heads in Grammatical Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 266-91. Hudson, Richard. 1994. Word Grammar. In Ronald Asher, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 4990-3. Hudson, Richard. 1995a. Does English really have case? Journal of Linguistics 31. Hudson, Richard. 1995b. Competence without Comp? In Bas Aarts and Charles Meyer (eds.) The Verb in Contemporary English. Cambridge: Cambridge Univesity Press, 40-53. Hudson, Richard. 1995c. Word Meaning. London: Routledge. Hudson, Richard. forthcoming. Really bare phrase-structure = Dependency structure. Studies in English Language Usage and English Language Teaching 17 (Kyoto: Yamaguchi). Iida, Masayo; Manning, Christopher; O'Neill, Patrick; & Sag, Ivan. 1994. The lexical integrity of Japanese causatives. Paper presented at the LSA 1994 Annual Meeting. Johnson, Mark. 1986. A GPSG account of VP structure in German. Linguistics 24;871-82. McCawley, James. 1982. Parentheticals and discontinuous constituent structure. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 91-106. Müller, Stefan. 1995. Message to the HPSG list = hpsg@ling.ohio-state.edu on 21st July. Nerbonne, John. 1994. Partial verb phrases and spurious ambiguities. In John Nerbonne, Klaus Netter & Carl Pollard (eds.) German Grammar in HPSG. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information. Pollard, Carl & Sag, Ivan. 1994. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Stanford: CSLI and Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rosta, Andrew. 1994. Dependency and grammatical relations. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 6, 219-58. Uszkoreit, Hans. 1987a. Linear precedence and discontinuous constituents: Complex fronting in German. In Geoffrey Huck & Almerindo Ojeda (eds.) Discontinuous Constituents = Syntax and Semantics 20, 406-27. Uszkoreit, Hans. 1987b. Word Order and Constituent Structure in German = CSLI Lecture Notes 8. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information. van Noord, Gertjan & Bouma, Gosse. 1995. Dutch verb clustering without verb clusters. MS. POSTSCRIPT Since writing this draft I've discovered more facts about German which undermine my proposed analysis of fronted partial VPs which include the subject. According to three native speakers (replying independently to a query on the HPSG network) the auxiliary verb agrees with the fronted subject: (59)Wirkliche Fehler unterlaufen waren ihm noch nie. `Real errors happened were ..' This seems to show beyond doubt that Fehler really is the subject of the auxiliary as well as of the infinitive. We therefore seem to have a clear example of subject lowering unless some clever alternative can be found .... Any suggestions gratefully received! Notice that this has nothing to do with PS, VP and so on - it's to do with the basic structure sharing mechanism. Does anyone know of any other examples of lowering?