Rationale of Ling

advertisement

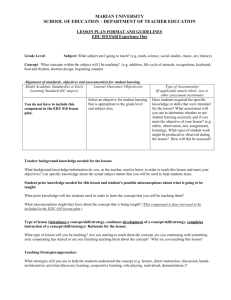

Rational: Ling’s Speech Development Model Due July 14th, 2010 Stepha Locke EPSE 565A Ling, Daniel (1976). Order or Chaos? Speech and the Hearing Impaired Child: Theory and Practice. 2nd edition. 2002. Washington DC: A.G. Bell. Ling proposed that his order is critical for three reasons: to avoid wasting time by working on a skill without the proper foundation, to avoid incorrect production and bad habits, and to avoid frustration both on the part of the student and on the part of the teacher. There are five hierarchical broad stages which overlap slightly, each with its own order of development within. It is important that speech sounds are learned in syllables, followed by practice at a phonetic level, and then used in communicative speech in a timely manner to provide meaning. Undifferentiated Vocalizations is the first broad stage, and with good reason. Page 111 introduced a study (Carr, 1953, 1955) of deaf’s children’s spontaneous vocalizations, explaining that many speech sounds are produced within those spontaneous vocalizations, and these should be used as the basis for development as we know the child can already produce them; therefore we are just prescribing meaning. Sounds not currently produced can be taught using the sounds the child already has. The second broad stage is Nonsegmental Patterns: pitch, intensity, and duration. These develop naturally in the hearing child from the beginning, and are necessary to teach before specific sounds so that the child has independent control of voice patterns and tongue movement. As pitch is the most difficult, due to lack of visual or tactile input available, loudness (intensity) should be taught first. It is also important to differentiate between intensity and pitch so that the child does not equate loudness with low pitch, and softness with high pitch (or vice versa). This is also the stage to introduce working on breath control. Everything developed in this stage will be used in future stages. Vowels are the third broad stage. Although the high-front vowels can be difficult for the hearing impaired child to learn, due to low visibility tongue placement and low acoustic properties, the placement should be taught early to avoid the habit of speaking too far back in the mouth (hypernasality). Ling advises high-front vowels be taught first, along with the low central and high back placements, concurrently. Tactile information is a useful tool to teach high front vowels; lip rounding should not be allowed to substitute for tongue placement. The second step within this stage includes low back vowels and low front vowels. Thirdly, moving between tongue positions is necessary for dipthongs, and can also help the child associate tongue placement with the vowels. Some vowels it is easier to teach from dipthongs instead of vice versa. Controlled tongue movements are even more important than the specific order vowels and dipthongs are taught in. Even while still teaching vowels, certain consonants will be necessary simply to work with the vowels; this brings us into the next broad stage: Simple Consonants. Consonants must be taught in three positions: initial, medial and final. Ling suggests that consonants differing in manner of production can and should be taught concurrently. Ling uses manner, place, and voicing to classify the sounds, as theses classifiers are specific without being too abstract. Within the broader stage of simple consonants, there are four steps. The first step sounds can be readily incorporated, as most do not involve the tongue and are simple to produce. The sounds in the second and third step vary only by place of production from the first step, and the sounds increase by complexity up to step four. Stops and plosives are treated differently as they function differently in speech and also differ physiologically. Lower frequency sounds are taught before the higher frequency sounds to provide auditory feedback to those with severe hearing loss; visual and ornosensory cues are also more readily available in earlier sounds. Other than certain nasals and fricatives, consonants can really only be taught properly as part of a syllable. It makes sense to teach voiceless fricatives before voiced fricatives for a number of reasons: voiceless are easier, and contrast with other sounds better so can be taught concurrently; reducing the voiceless sound can sometimes produce the voiced (but not the other way around); it can help with hypernasality; there is a foundation in the whispering work done in vowels and dipthongs. Manner of production carries the most information when it comes to speech, followed by duration, followed by place and finally voicing. Place is more crucial to intelligibility than voicing (for example, whispering is without voice). Voice is more about breath control and is therefore limited in syllable teaching. Manner and place should be automatic before timing can be taught. First proper vowel duration is necessary (rice versus rise) and then the duration of vowel consonant interaction can be worked on, followed by voice onset time (VOT). VOT is very consistent with consonants and can therefore help differentiate between them, making it easier to build on what is already in place. Once certain consonants are mastered, it is necessary to teach consonant blends. Consonant blends are a compound, and each component must be strong before you can work at combining them. It is important to remember that the elements can change in the blending process, thereby acting not as two letters but as a single form; affricates can be used to help develop blends. Just as consonants, blends can be in the initial placement, the medial placement (medial lexical), or the final placement; there are also blends that happen between words (interlexical blends), but they function similar to medial lexical blends. Initial blends should be taught by organic difficulty (easiest to hardest). First the two-organ sequentially formulated blends (such as /sm/) should be taught because each sound is produced sequentially (the /s/ is formed and then the /m/), and producing a blend using both the lips and tongue is easier than forming a blend using the tongue alone. Those blends using the tongue alone are called the one organ sequentially formulated blends when each sound is still produced sequentially (/sn/), and should be taught next. Thirdly, two organ simultaneously formulated blends can be taught; in these the second element must be partially formed before the first element is completed (/br/). Fourth, one organ simultaneously formulated blends are taught; these contain the most radically changed elements: if the first element is unvoiced, so is the second (/tr/). Lastly, complex blends can be taught when the other four types are mastered; these combine various types of blends (/spr/). Final blends should also be taught by organic difficulty, and again there are four types and then complex blends. First, continuant-continuant blends should be taught, as their elements are not radically changed but rather juxtaposed (/ns/). Continuant-stop blends are taught next; in these the second element cannot be formulated until the first element is completed (/st/), and sometimes releasing the second element is only necessary when followed by a word beginning with a vowel. Thirdly, stop-consonant blends should be taught, where the stop as the first element is unreleased (/ts/). Final stops must be mastered before teaching this blend. Fourth, stop-stop blends are taught (/pt/); these are the most difficult to learn, and /t/ in isolation must be mastered before this skill is taught. Lastly, complex blends can be taught once mastery of the simpler blends is achieved (/sps/). Medial-lexical blends (and interlexical or between word blends) include many more combinations of sounds than other blends. The teacher needs to be aware how blends change the characteristics of the individual sounds, and mastery of the previous broad stages are necessary so the student can concentrate on the blend as oppose to tongue position. Quick succession of one syllable words can help work on medial lexical and interlexical blends (“big-dog”) Ling admits that at the time he wrote this article, there was not a lot of research to support his sequential and slightly overlapping stages of development, which is why his rational (and therefore this one) is so extensive. I might add that the fact we are still using Ling’s sequence at this point in time, decades later, is a bit of a rational in itself. I assume there is now adequate research to support Ling’s theories (although I haven’t done extensive investigation myself).