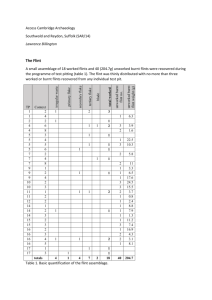

Flint Report

advertisement

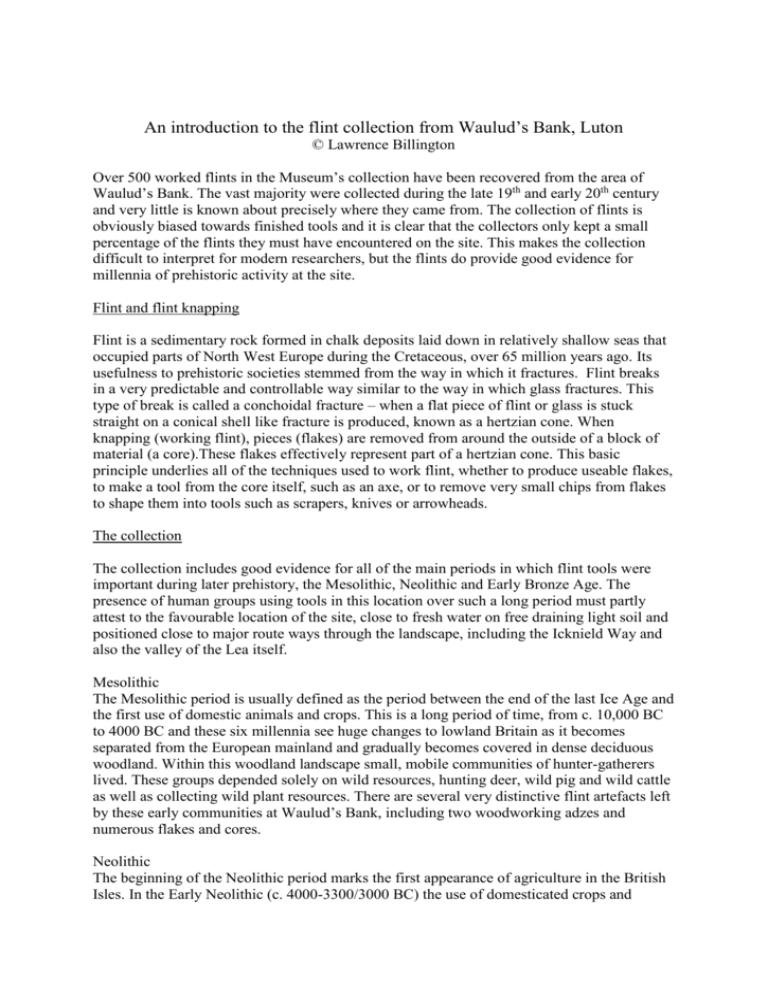

An introduction to the flint collection from Waulud’s Bank, Luton © Lawrence Billington Over 500 worked flints in the Museum’s collection have been recovered from the area of Waulud’s Bank. The vast majority were collected during the late 19th and early 20th century and very little is known about precisely where they came from. The collection of flints is obviously biased towards finished tools and it is clear that the collectors only kept a small percentage of the flints they must have encountered on the site. This makes the collection difficult to interpret for modern researchers, but the flints do provide good evidence for millennia of prehistoric activity at the site. Flint and flint knapping Flint is a sedimentary rock formed in chalk deposits laid down in relatively shallow seas that occupied parts of North West Europe during the Cretaceous, over 65 million years ago. Its usefulness to prehistoric societies stemmed from the way in which it fractures. Flint breaks in a very predictable and controllable way similar to the way in which glass fractures. This type of break is called a conchoidal fracture – when a flat piece of flint or glass is stuck straight on a conical shell like fracture is produced, known as a hertzian cone. When knapping (working flint), pieces (flakes) are removed from around the outside of a block of material (a core).These flakes effectively represent part of a hertzian cone. This basic principle underlies all of the techniques used to work flint, whether to produce useable flakes, to make a tool from the core itself, such as an axe, or to remove very small chips from flakes to shape them into tools such as scrapers, knives or arrowheads. The collection The collection includes good evidence for all of the main periods in which flint tools were important during later prehistory, the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. The presence of human groups using tools in this location over such a long period must partly attest to the favourable location of the site, close to fresh water on free draining light soil and positioned close to major route ways through the landscape, including the Icknield Way and also the valley of the Lea itself. Mesolithic The Mesolithic period is usually defined as the period between the end of the last Ice Age and the first use of domestic animals and crops. This is a long period of time, from c. 10,000 BC to 4000 BC and these six millennia see huge changes to lowland Britain as it becomes separated from the European mainland and gradually becomes covered in dense deciduous woodland. Within this woodland landscape small, mobile communities of hunter-gatherers lived. These groups depended solely on wild resources, hunting deer, wild pig and wild cattle as well as collecting wild plant resources. There are several very distinctive flint artefacts left by these early communities at Waulud’s Bank, including two woodworking adzes and numerous flakes and cores. Neolithic The beginning of the Neolithic period marks the first appearance of agriculture in the British Isles. In the Early Neolithic (c. 4000-3300/3000 BC) the use of domesticated crops and animals appears alongside a series of other transformations visible in the archaeological record, including the use of pottery, new flint tools and the construction of the first monuments, including large earthwork enclosures and tombs or ancestral shrines for housing remains of the dead. Although these changes are dramatic, Neolithic communities appeared to have remained relatively mobile and the landscape remained largely unaltered, often with only small temporary clearances being made in the extensive woodland. There is a large amount of Early Neolithic flint work from Waulud’s Bank and it seems possible that the site was a place of some importance at this time. Several Early Neolithic monuments including an enclosure and several long barrows were constructed close by, around the upper reaches of the Lea Valley which appears to have been a significant area during this time. The flints from Waulud’s Bank include finely made leaf shaped arrowheads, several knives or spearheads known as laurel leaves, polished stone axe heads, scrapers and other tools. The Late Neolithic (c. 3300/3000-2400 BC) sees some changes in the flint tools and pottery that societies were using. There are also changes in the monuments that were constructed, the tombs and enclosures of the earlier period fell into disuse and new monument forms, including the circular earthworks known as henges, were constructed. Later Neolithic flint is less well represented at Waulud’s Bank than Early Neolithic material although the flints still indicate a substantial presence in this period. Early Bronze Age The Early Bronze Age (c. 2400-1600BC, now often separated into an early ‘Chalcolithic’ and a later true Early Bronze Age), sees the first appearance of metal tools in this country. Other changes in society accompanied the use of metal, including new kinds of pottery and a gradual abandonment of the large communal monuments of the Neolithic in favour of the construction of circular burial mounds in which the remains of individuals, sometimes accompanied by rich grave goods, were deposited. Despite the use of metal flint remained a very important source of material for tools and it seems that in the Early Bronze Age only stone axes were more or less completely replaced by metal equivalents. The Waulud’s Bank assemblage contains a high proportion of Early Bronze Age material, including arrowheads, knives and distinctive scrapers, all characteristic of Early Bronze Age settlement sites from southern Britain. Later prehistory As metal tools became more important and settlement patterns become more sedentary from the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1600-1200 BC) onwards the functional and social importance of stone tools declined. Flint tools continued to be used into the Iron Age but the skill of earlier stone workers was largely lost and fewer formal tools were produced. There is no clear evidence for later prehistoric flintwork in the Waulud’s Bank collection, although this may reflect the biases of the early collectors as they may have not been disposed to collect crudely worked and unattractive artefacts! Tool types The collection from Waulud’s Bank is dominated by formal tool types. Some of the most common tool types and their functions are described below. Determining the function of stone tools is not straightforward. Often tool function is suggested by making analogies with tools used today or in the recent past. The study of microscopically visible use wear on stone tools has also allowed the function of some tool types to be determined. Scrapers Scrapers are generally the most common tool type recovered from prehistoric flint assemblages. They are generally made by removing small flakes from the end of fairly robust flakes to create a steep angle suitable for use in a scraping motion. Some scrapers may have been hafted in a handle but most were probably hand held. The main use of scrapers appears to have been for the preparation of animal skins to make hides and leathers by scraping unwanted tissue from the skin and softening the hide. Scrapers were sometimes also used on other materials however, including wood and bone. Arrowheads Arrowheads are well represented in the collection from Waulud’s Bank. The form of arrowheads changed throughout prehistory. Leaf shaped piercing arrowheads were used during the Early Neolithic but went out of use in the Late Neolithic, when they were replaced with a variety of arrowheads including asymmetrical piercing forms (oblique arrowheads) and pieces with a broad, thin cutting edge (chisel arrowheads). The Early Bronze Age sees the development of barbed and tanged arrowheads, a form that is perhaps most familiar to us today. Arrowheads were used both for hunting and warfare. Their use in warfare may have been particularly important in the Early Neolithic, a number of human skeletons have been found with arrowheads imbedded in their bones and at several enclosures in southern Britain large numbers of arrowheads have been interpreted as marking violent battles between different communities. Axes Unsurprisingly, the main use of axes appears to have been for woodworking tasks. The flaked axes and adzes of the Mesolithic appear to be more suited to light tasks such as cutting round wood or shaping tools and it seems unlikely they were often used for felling larger trees. The polished axes of the Neolithic, however, have been shown to be very effective felling tools in the right hands and must have been an important tool for helping to create and maintain clearings for growing crops and grazing animals. Polished axe heads were often made of nonlocal ‘special’ raw material and grinding and polishing would have entailed a considerable investment of time. It seems likely that polished axes were important and cherished items, perhaps rich in symbolic meaning. Other tools The other tools in the collection are dominated by various forms of cutting tools and also include piercers and several rod shaped tools known as fabricators which were probably used to strike sparks for fire lighting.