The Sanity of Furor Poeticus: Romanticism`s

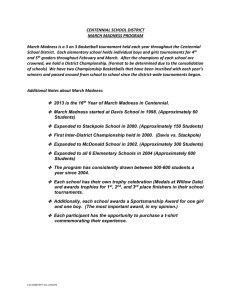

advertisement