Word Version Final Protocol - the Medical Services Advisory

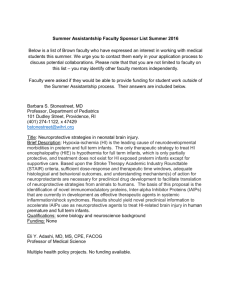

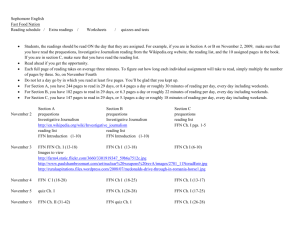

advertisement