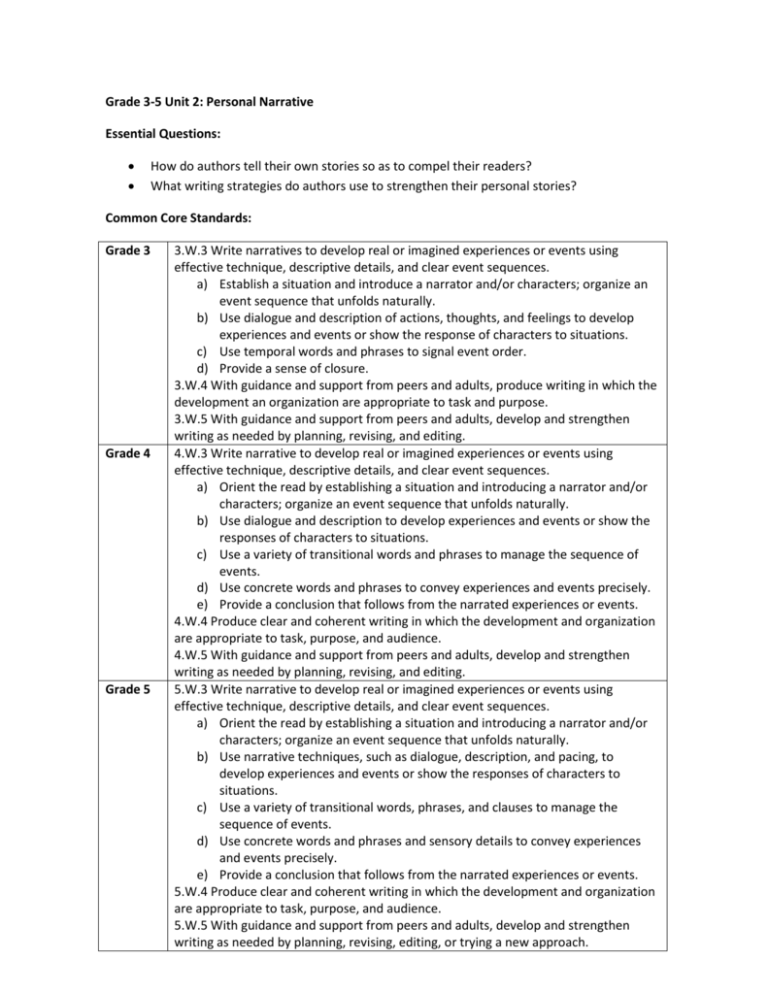

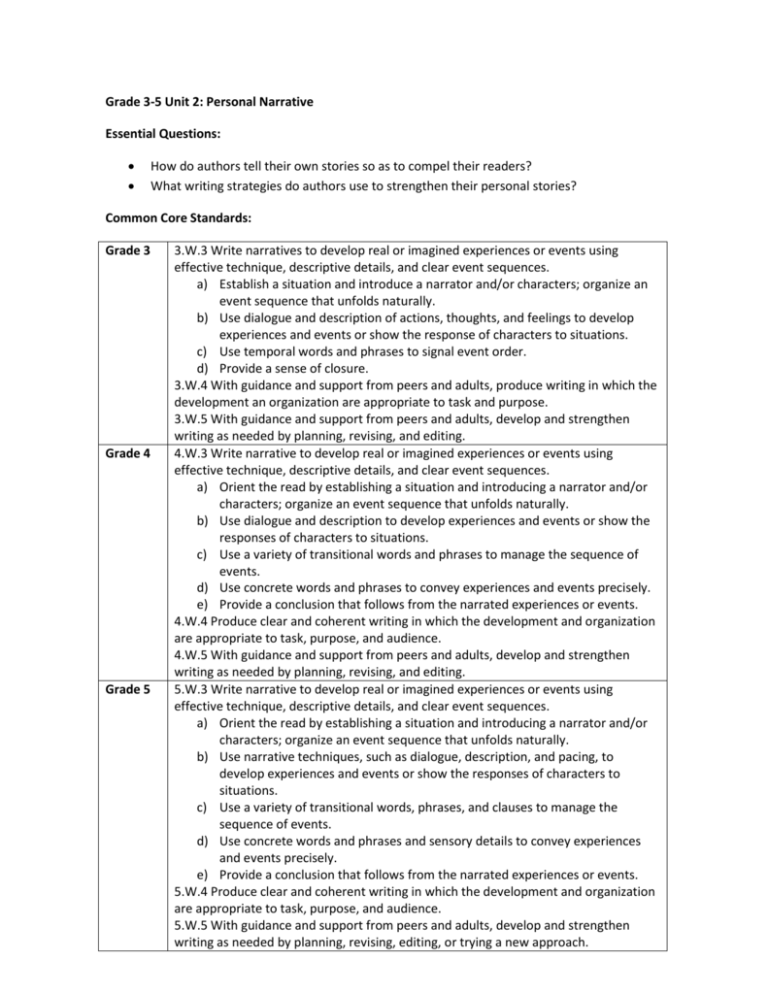

Grade 3-5 Unit 2: Personal Narrative

Essential Questions:

How do authors tell their own stories so as to compel their readers?

What writing strategies do authors use to strengthen their personal stories?

Common Core Standards:

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

3.W.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using

effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

a) Establish a situation and introduce a narrator and/or characters; organize an

event sequence that unfolds naturally.

b) Use dialogue and description of actions, thoughts, and feelings to develop

experiences and events or show the response of characters to situations.

c) Use temporal words and phrases to signal event order.

d) Provide a sense of closure.

3.W.4 With guidance and support from peers and adults, produce writing in which the

development an organization are appropriate to task and purpose.

3.W.5 With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen

writing as needed by planning, revising, and editing.

4.W.3 Write narrative to develop real or imagined experiences or events using

effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

a) Orient the read by establishing a situation and introducing a narrator and/or

characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally.

b) Use dialogue and description to develop experiences and events or show the

responses of characters to situations.

c) Use a variety of transitional words and phrases to manage the sequence of

events.

d) Use concrete words and phrases to convey experiences and events precisely.

e) Provide a conclusion that follows from the narrated experiences or events.

4.W.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development and organization

are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

4.W.5 With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen

writing as needed by planning, revising, and editing.

5.W.3 Write narrative to develop real or imagined experiences or events using

effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

a) Orient the read by establishing a situation and introducing a narrator and/or

characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally.

b) Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, description, and pacing, to

develop experiences and events or show the responses of characters to

situations.

c) Use a variety of transitional words, phrases, and clauses to manage the

sequence of events.

d) Use concrete words and phrases and sensory details to convey experiences

and events precisely.

e) Provide a conclusion that follows from the narrated experiences or events.

5.W.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development and organization

are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

5.W.5 With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen

writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, or trying a new approach.

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Write personal narratives that use strategies to strengthen ideas, organization, and word

choice.

Use the strategy “show don’t tell” to strengthen their ideas.

Plan their writing to support drafting of their ideas.

Write leads and endings that engage the readers in the story.

Use precise nouns, action verbs, and choice adjectives in their writing.

Revise their writing for ideas, organization, and word choice.

Edit their writing using a checklist.

Key Academic Vocabulary:

Personal narrative

Story elements: Plot, character, setting

Parts of Speech: Nouns, adjectives, verbs

Six Traits of Writing: Ideas, organization, word choice, conventions

Outline of Unit 2: Personal Narrative

Day 1

Introducing

Mentor Text: The

Genre of

Personal

Narrative

Day 6

Bring Your

Characters to Life

Trait: Ideas

Day 11

Making a Plan

Trait:

Organization

Day 16

Use Choice

Adjectives

Trait: Word

Choice

Day 21

Choose a seed

idea for personal

narrative

Day 26

Revise for ideas,

organization, and

word choice

based upon

lessons for the

unit.

Day 7

Day 12

Using Transition

Words

Trait:

Organization

Day 17

Day 22

Create a timeline

for seed idea

Day 27

Use Editing

Checklist

Day 3

Use Plot, Place,

and Character in

a Story

Trait: Ideas and

Organization

Day 8

Describe What

Your Characters

Look Like

Trait: Ideas

Day 13

Write a Lively

Lead

Trait:

Organization

Day 18

Use Precise

Nouns

Trait: Word

Choice

Day 23

Begin drafting

about #1 only

Day 28

Final Draft

Day 5

Show Don’t Tell

Trait: Ideas

Day 9

Using Dialogue

to Bring

Characters to

Life Trait: Ideas

Day 14

Day 19

Day 24

Continue

drafting

Day 29

Final Draft

Day 10

Use Details to

Bring the Setting

Alive

Trait: Ideas

Day 15

Come Up with

the Right Ending

Trait:

Organization

Day 20

Use Verbs that

Describe

Trait: Word

Choice

Day 25

Continue drafting

Day 30

Author’s

Celebration

Day One: Introducing Mentor Text: The Genre of Personal Narrative

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific

that you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you

will reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly

how to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Identify the difference between reading a piece as a reader and

reading as a writer.

Name several strategies used by mentor authors in writing

personal narratives.

Copies of “Eleven” and other mentor personal narratives

I am so excited about the writing that you have done so far this year. I

know that your stories are important to you, but I have also noticed that

your writing really matters to your readers too. I noticed… [Share a few

anecdotes about the students’ writing has affected their readers.]

So I want you to remember that your writing matters because you are

writing for your readers.

Today we are starting a new unit of study about personal narrative

writing, and this time your goal is to write even more powerful stories,

stories that will make your readers laugh, cry, get angry, or think about

something in a new way. You have that power as writers and I can’t wait

to help you get started!

Today I want to teach you that one way to make your writing powerful is

to study the work of published authors. We can read their writing and

then ask, “What did this author do that I could do in my writing?”

I want to share a piece of writing by Sandra Cisneros with you today. This

story is called “Eleven.” I chose this text there are parts of the story that

resemble the kind of writing that you will try to do in this unit. This story

will be our mentor text. Listen and watch as I read and experience this

story. [Read aloud and demonstrate experiencing the story. To show

this, act out small parts such as Mrs. Price holding the sweater with

disdain between two fingers. Stop periodically to think aloud and point

out how you are “experiencing” the story. Read up to the line in the

story that reads “Not mine, not mine, not mine.”]

I can really picture this story in my mind! I felt like I was Rachel, moving

that red sweater to the corner of my desk with a ruler so that I didn’t

have to touch it!

Active Engagement

Now, I need to think like a writer. As a writer, I need to stop and ask

myself, “What do I notice about this story? What has Sandra Cisneros

done that I could try the next time I write a story?” I call this reading with

my writer’s eye. Let me take a look at the story using my writer’s eye.

Hmmm…. I notice that Cisneros has written about one small episode in

her life, one that other people might not think was very important, but

one that I think really mattered to her. [Add this idea to anchor chart.] I

also notice that this author writes her story from so much detail that I

feel like I am right there reliving every moment. One way Cisneros does

this is by using the exact words that Mrs. Price said. [Add this idea to

anchor chart.]

Let’s try this together. I’ll continue reading. As I read, I want you to

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it

with me…”

experience this text and make a movie in your mind. [Read aloud “Eleven

from “Not mine, not mine, not mine.” to “all itchy and full of germs that

aren’t mine.”]

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Have students look through different examples of personal narrative.

Have them look and record in their notebooks what qualities of writing

do they observe in what they read.

Independent Writing

So, I want you to always remember that writers learn from other writers.

As a writer, you must read in two ways. First, read to experience the

story. Then, really read like a writer. Study stories and ask yourself,

“What has this writer done that I could try?” This study will make your

writing even better and more powerful!

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Now, I’ll reread the same section and I want you to really think like a

writer. Notice what Sandra Cisneros does that allows you to experience

her story and ask yourself, “What could I try in my writing?” [Reread

section of text.] Turn and talk to your partner about what you noticed.

[Share a few ideas and add to anchor chart.]

Today during independent writing continue your study of personal

narrative writing. There is a collection of personal narratives at each

table. Read and experience these stories. Then study them with your

writer’s eye. List what the authors have done that you can try. We’ll

work quietly for about 15 minutes and then come back together to share.

Have students share one part of a personal narrative with a partner that

they found powerful.

Ask: What did your writer’s eye notice about these stories? Who found

something in a story that they plan to try in their own writing?

Have students name some of the key qualities of personal narratives that

they discover and record on an anchor chart. For example, an anchor

chart might include the following:

1. Write about a small moment

2. Details make you feel you are there.

3. Show rather than tell.

4. Convey strong feelings

“Eleven” by Sandra Cisneros.

What they don't understand about birthdays and what they never tell you is that when

you're eleven, you're also ten, and nine, and eight, and seven, and six, and five, and four,

and three, and two, and one. And when you wake up on your eleventh birthday you

expect to feel eleven, but you don't. You open your eyes and everything's just like

yesterday, only it's today. And you don't feel eleven at all. You feel like you're still ten.

And you are—underneath the year that makes you eleven.

Like some days you might say something stupid, and that's the part of you that's still ten.

Or maybe some days you might need to sit on your mama's lap because you're scared,

and that's the part of you that's five. And maybe one day when you're all grown up maybe

you will need to cry like if you're three, and that's okay. That's what I tell Mama when

she's sad and needs to cry. Maybe she's feeling three.

Because the way you grow old is kind of like an onion or like the rings inside a tree trunk

or like my little wooden dolls that fit one inside the other, each year inside the next one.

That's how being eleven years old is.

You don't feel eleven. Not right away. It takes a few days, weeks even, sometimes even

months before you say Eleven when they ask you. And you don't feel smart eleven, not

until you're almost twelve. That's the way it is.

Only today I wish I didn't have only eleven years rattling inside me like pennies in a tin

Band-Aid box. Today I wish I was one hundred and two instead of eleven because if I

was one hundred and two I'd have known what to say when Mrs. Price put the red

sweater on my desk. I would've known how to tell her it wasn't mine instead of just

sitting there with that look on my face and nothing coming out of my mouth.

"Whose is this?" Mrs. Price says, and she holds the red sweater up in the air for all the

class to see. "Whose? It's been sitting in the coatroom for a month."

"Not mine," says everybody, "Not me."

"It has to belong to somebody," Mrs. Price keeps saying, but nobody can remember. It's

an ugly sweater with red plastic buttons and a collar and sleeves all stretched out like you

could use it for a jump rope. It's maybe a thousand years old and even if it belonged to

me I wouldn't say so.

Maybe because I'm skinny, maybe because she doesn't like me, that stupid Sylvia Saldivar

says, "I think it belongs to Rachel." An ugly sweater like that all raggedy and old, but

Mrs. Price believes her. Mrs Price takes the sweater and puts it right on my desk, but

when I open my mouth nothing comes out.

"That's not, I don't, you're not . . . Not mine." I finally say in a little voice that was maybe

me when I was four.

"Of course it's yours," Mrs. Price says. "I remember you wearing it once." Because she's

older and the teacher, she's right and I'm not.

Not mine, not mine, not mine, but Mrs. Price is already turning to page thirty-two, and

math problem number four. I don't know why but all of a sudden I'm feeling sick inside,

like the part of me that's three wants to come out of my eyes, only I squeeze them shut

tight and bite down on my teeth real hard and try to remember today I am eleven, eleven.

Mama is making a cake for me for tonight, and when Papa comes home everybody will

sing Happy birthday, happy birthday to you.

But when the sick feeling goes away and I open my eyes, the red sweater's still sitting

there like a big red mountain. I move the red sweater to the corner of my desk with my

ruler. I move my pencil and books and eraser as far from it as possible. I even move my

chair a little to the right. Not mine, not mine, not mine.

In my head I'm thinking how long till lunchtime, how long till I can take the red sweater

and throw it over the schoolyard fence, or leave it hanging on a parking meter, or bunch it

up into a little ball and toss it in the alley. Except when math period ends Mrs. Price says

loud and in front of everybody, "Now, Rachel, that's enough," because she sees I've

shoved the red sweater to the tippy-tip corner of my desk and it's hanging all over the

edge like a waterfall, but I don't care.

"Rachel," Mrs. Price says. She says it like she's getting mad. "You put that sweater on

right now and no more nonsense."

"But it's not—"

"Now!" Mrs. Price says.

This is when I wish I wasn't eleven because all the years inside of me—ten, nine, eight,

seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one—are pushing at the back of my eyes when I put

one arm through one sleeve of the sweater that smells like cottage cheese, and then the

other arm through the other and stand there with my arms apart like if the sweater hurts

me and it does, all itchy and full of germs that aren't even mine.

That's when everything I've been holding in since this morning, since when Mrs. Price

put the sweater on my desk, finally lets go, and all of a sudden I'm crying in front of

everybody. I wish I was invisible but I'm not. I'm eleven and it's my birthday today and

I'm crying like I'm three in front of everybody. I put my head down on the desk and bury

my face in my stupid clown-sweater arms. My face all hot and spit coming out of my

mouth because I can't stop the little animal noises from coming out of me until there

aren't any more tears left in my eyes, and it's just my body shaking like when you have

the hiccups, and my whole head hurts like when you drink milk too fast.

But the worst part is right before the bell rings for lunch. That stupid Phyllis Lopez, who is

even dumber than Sylvia Saldivar, says she remembers the red sweater is hers! I take it off right

away and give it to her, only Mrs. Price pretends like everything's okay.

Today I'm eleven. There's a cake Mama's making for tonight and when Papa comes home from

work we'll eat it. There'll be candles and presents and everybody will sing Happy birthday,

happy birthday to you, Rachel, only it's too late.

I'm eleven today. I'm eleven, ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one, but I

wish I was one hundred and two. I wish I was anything but eleven, because I want today to be

far away already, far away like a runaway balloon, like a tiny o in the sky, so tiny tiny you

have to close your eyes to see it.

Your Name in Gold

Anne sat at the breakfast table, eating her cornflakes and reading the print on the cereal box in

front of her. "Tastee Cornflakes - Great New Offer!" the box read. "See back of box for details."

Anne’s older sister, Mary, sat across from her, reading the other side of the cereal box. "Hey,

Anne," she said, "look at this awesome prize - ‘your name in gold’."

As Mary read on, Anne’s interest in the prize grew. "Just send in one dollar with proof-ofpurchase seal from this box and spell out your first name on the information blank. We will send

you a special pin with your name spelled in gold. (Only one per family, please.)"

Anne grabbed the box and looked on the back, her eyes brightening with excitement. The name

"Jennifer" was spelled out in sparkling gold. "That’s a neat idea," she said. "A pin with my very

own name spelled out in gold. I’m going to send in for it."

"Sorry, Anne, I saw it first," said Mary, "so I get first dibs on it. Besides,

you don’t have a dollar to send in, and I do."

"But I want a pin like that so badly," said Anne. "Please let me have it!"

"Nope," said her sister.

"You always get your way - just because you’re older than me," said Anne, her lower lip

trembling as her eyes filled with tears. "Just go ahead and send in for it. See if I care!" She

threw down her spoon and ran from the kitchen.

Several weeks passed. One day the mailman brought a small package addressed to Mary.

Anne was dying to see the pin, but she wouldn’t let Mary know how eager she was. Mary took

the package to her room. Anne casually followed her in and sat on the bed.

"Well, I guess they sent you your pin. I sure hope you like it," Anne said in a mean voice. Mary

slowly took the paper off the package. She opened a little white box and carefully lifted off the

top layer of white cotton. "Oh, it’s beautiful!" Mary said. "Just like the cereal box said, ‘your

name in gold’. Four beautiful letters. Would you like to see it, Anne?"

"No, I don’t care about your dumb old pin."

Mary put the white box on the dresser and went downstairs.

Anne was alone in the bedroom. Soon she couldn’t wait any longer, so she walked over to the

dresser. As she looked in the small white box, she gasped. Mixed feelings of love for her sister

and shame at herself welled up within her, and the pin became a sparkling gold blur through her

tears.

There on the pin were four beautiful letters - her name in gold: A-N-N-E.

By A. F. Bauman

from Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul

Copyright 1998 by Jack Canfield, Mark Victor Hansen, Patty Hansen and Irene Dunlap

(There are 5 selections here from the book The House on Mango Street. The first selection has the

same title as the book.)

1) The House on Mango Street

We didn't always live on Mango Street. Before that we lived on Loomis on the third

floor, and before that we lived on Keeler. Before Keeler it was Paulina, and before that I can't

remember. But what I remember most is moving a lot. Each time it seemed there'd be one

more of us. By the time we got to Mango Street we were six—Mama, Papa, Carlos, Kiki, my

sister Nenny and me.

The house on Mango Street is ours, and we don't have to pay rent to anybody, or share

the yard with the people downstairs, or be careful not to make too much noise, and there

isn't a landlord banging on the ceiling with a broom. But even so, it's not the house we'd

thought we'd get.

We had to leave the flat on Loomis quick. The water pipes broke and the landlord wouldn't

fix them because the house was too old. We had to leave fast. We were using the washroom next

door and carrying water over in empty milk gallons. That's why Mama and Papa looked for a

house, and that's why we moved into the house on Mango Street, far away, on the other side of

town.

They always told us that one day we would move into a house, a real house that would be ours

for always so we wouldn't have to move each year. And our house would have running water and

pipes that worked. And inside it would have real stairs, not hallway stairs, but stairs inside like the

houses on T.V. And we'd have a basement and at least three washrooms so when we took a bath

we wouldn't have to tell everybody. Our house would be white with trees around it, a great big yard

and grass growing without a fence. This was the house Papa talked about when he held a lottery

ticket and this was the house Mama dreamed up in the stories she told us before we went to

bed.

But the house on Mango Street is not the way they told it at all. It's small and red with tight

steps in front and windows so small you'd think they were holding their breath. Bricks are

crumbling in places, and the front door is so swollen you have to push hard to get in. There is no

front yard, only four little elms the city planted by the curb. Out back is a small garage for the car

we don't own yet and a small yard that looks smaller between the two buildings on either side.

There are stairs in our house, but they're ordinary hallway stairs, and the house has only one

washroom. Everybody has to share a bedroom—Mama and Papa, Carlos and Kiki, me and Nenny.

Once when we were living on Loomis, a nun from my school passed by and saw me playing out

front. The laundromat downstairs had been boarded up because it had

been robbed two days before and the owner had painted on the wood YES WE'RE OPEN so as not

to lose business.

Where do you live? she asked.

There, I said pointing up to the third floor.

You live there?

There. I had to look to where she pointed—the third floor, the paint peeling, wooden bars

Papa had nailed on the windows so we wouldn't fall out. You live there? The way she said it made

me feel like nothing. There. I lived there. I nodded.

I knew then I had to have a house. A real house. One I could point to. But this isn't it. The

house on Mango Street isn't it. For the time being, Mama says. Temporary, says Papa. But I know

how those things go.

2) My Name

In English my name means hope. In Spanish it means too many letters. It means sadness,

it means waiting. It is like the number nine. A muddy color. It is the Mexican records my

father plays on Sunday mornings when he is shaving, songs like sobbing.

It was my great-grandmother's name and now it is mine. She was a horse woman too,

born like me in the Chinese year of the horse—which is supposed to be bad luck if you're

born female—but I think this is a Chinese lie because the Chinese, like the Mexicans, don't

like their women strong.

My great-grandmother. I would've liked to have known her, a wild horse of a woman,

so wild she wouldn't marry. Until my great-grandfather threw a sack over her head and

carried her off. Just like that, as if she were a fancy chandelier. That's the way he did it.

And the story goes she never forgave him. She looked out the window her whole life, the

way so many women sit their sadness on an elbow. I wonder if she made the best with what

she got or was she sorry because she couldn't be all the things she wanted to be. Esperanza. I

have inherited her name, but I don't want to inherit her place by the window.

At school they say my name funny as if the syllables were made out of tin and hurt the

roof of your mouth. But in Spanish my name is made out of a softer something, like silver,

not quite as thick as sister's name— Magdalena—which is uglier than mine. Magdalena who at

least can come home and become Nenny. But I am always Esperanza.

I would like to baptize myself under a new name, a name more like the real me, the

one nobody sees. Esperanza as Lisandra or Maritza or Zeze the X. Yes. Something like Zeze the

X will do.

3) Hairs

Everybody in our family has different hair. My Papa's hair is like a broom, all up in the air.

And me, my hair is lazy. It never obeys barrettes or bands. Carlos' hair is thick and straight. He

doesn't need to comb it. Nenny's hair is slippery—slides out of your hand. And Kiki, who is

the youngest, has hair like fur.

But my mother's hair, my mother's hair, like little rosettes, like little candy circles all curly

and pretty because she pinned it in pincurls all day, sweet to put your nose into when she is

holding you, holding you and you feel safe, is the warm smell of bread before you bake it, is

the

smell when she makes room for you on her side of the bed still warm with her skin, and you

sleep near her, the rain outside falling and Papa snoring. The snoring, the rain, and Mama's

hair that smells like bread.

4) Bums in the Attic

I want a house on a hill like the ones with the gardens where Papa works. We go on

Sundays, Papa's day off. I used to go. I don't anymore. You don't like to go out with us, Papa

says. Getting too old? Getting too stuck-up, says Nenny. I don't tell them I am ashamed—all

of us staring out the window like the hungry. I am tired of looking at what we can't have.

When we win the lottery... Mama begins, and then I stop listening.

People who live on hills sleep so close to the stars they forget those of us who live too

much on earth. They don't look down at all except to be content to live on hills. They have

nothing to do with last week's garbage or fear of rats. Night comes. Nothing wakes them but

the wind.

One day I'll own my own house, but I won't forget who I am or where I came from.

Passing bums will ask, Can I come in? I'll offer them the attic, ask them to stay, because I

know how it is to be without a house.

Some days after dinner, guests and I will sit in front of a fire. Floorboards will squeak

upstairs. The attic grumble.

Rats? they'll ask.

Bums, I'll say, and I'll be happy.

3) Papa Who Wakes up Tired in the Dark

Your abuelito is dead, Papa says early one morning in my room. Estad muerto, and then

as if he just heard the news himself, crumples like a coat and cries, my brave Papa cries. I have

never seen my Papa cry and don't know what to do.

I know he will have to go away, that he will take a plane to Mexico, all the uncles and

aunts will be there, and they will have a black and white photo taken in front of the tomb

with flowers shaped like spears in a white vase because this is how they send the dead away

in that country. Because I am the oldest, my father has told me first, and now it is my turn to

tell the others. I will have to explain why we can't play. I will have to tell them to be quiet today.

My Papa, his thick hands and thick shoes, who wakes up tired in the dark, who combs his hair

with water, drinks his coffee, and is gone before we wake, today is sitting on my bed.

And I think if my own Papa died what would I do. I hold my Papa in my arms. I hold and

hold and hold him.

--from The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

First Pen, from Marshfield Dreams

By Ralph Fletcher

When I was eight Dad bought me my first pen. It just a cheapo BOC, the kind with a clear

barrel so you could see how much ink it left in the cartridge, but I loved it. In school we wrote in

pencil, and it made me feel grown up to be putting inked words onto the page.

With that pen, and a brand new notebook, I made my first story. I wrote it on a rainy

Sunday, sitting at the kitchen table while Mom made caramel applies with the little kids. The

story was about a Major League baseball player who batted 1,000 during his rookie year. The

kid was amazing-he got a hot every time he came to bat. No pitcher could figure out how to get

him out!

It was fun writing that story. And it felt like a small miracle, too: first there was nothing

on the page, then the story appeared, written in ink that couldn’t be erased.

I sat for a long time, wondering what to write next. I stared at my BIC pen, the cartridge

filled with ink so blue it was almost black. What words were hidden-unborn, unwritten-in all

that unused ink?

Day Three: Using Plot, Place, and Character in a Story

Focus Lesson Topic

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Identify plot, character, and setting as elements of narrative.

Identify plot, character, and setting in their own and peer’s writing.

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Copies of “Teeth” from Marshfield Dreams, by Ralph Fletcher, to hand

out to your students

Chart papers and markers

Other picture books for repeating the lesson include The Gardener by

Sarah Stewart, Fly Away Home by Eve Bunting, Brave Irene by William

Steig, and Fox by Margaret Wild.

We have been discussing an important question, “What do you need to

include in order to write a strong story?”

Let’s start by hearing a short story by Ralph Fletcher. We are going to read

like a writer like we did in previous lessons.

Read the story to the students.

Ask students, “What did you notice? What surprised you?”

Draw a Venn diagram with three circles, labeled plot, setting, and character.

Place the label “story” in the intersection of all three circles.

Most stories we read and write are built on three pillars: plot, the setting, and

characters. The combination of plot, place, and character results in the story.

There are other elements, but we’re going to concentrate on these three. Let’s

see what parts they play in the story we just read.

Ask students, “Who are the characters in ‘Teeth?’”

Discuss and write them down. Do the same thing with plot and setting.

Students may note that the story takes place both inside and outside the

house.

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

When you write a story-whether it’s true or a work of fiction-make sure you

have these three elements in your writing. Make sure you have included

enough details and examples so the reader can picture them clearly.

Independent Writing

Possible Conference Questions:

When you reread your story, point out where you have included these

elements.

Find a place where you may need to add details or examples to

strengthen the character, setting, or plot.

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Turn to your partner and describe the plot, setting, and characters in the story

you have been working on.

Turn to your partner and share where you describe the setting.

(While plot, place, and character are not present in every single story, the vast

majority do include all three. Unfortunately, these three elements don’t

always show up in student writing. You’ll probably find that all students have

plot, most use characters, but relatively few bother to develop the setting.)

Teeth, from Marshfield Dreams by Ralph Fletcher

Mom had a “tooth bank” shaped like

a coconut. When one of our teeth came

out, she washed off the blood and

deposited it into that bank.

“Why are you saving our teeth?” my

brother Jimmy wanted to know.

“Because.” She smiled at him.

“They’re precious to me. And so are you.”

Great Grandma came to visit two or

three times a year. She was old and tiny,

and it took her a long time to get anywhere

because she walked so slowly. She always

wore a gray sweatshirt way too big for her,

and always smelled like the gingersnap

cookies she baked. She put whole chunks of

ginger into the cookies, so when I bit into

them they were so spicy they made my eyes

water. But I loved her with all my heart, and

pretended to love those cookies so I

wouldn’t hurt her feelings.

Early one morning I heard her

outside my bedroom, going downstairs. I

waited until she reached the bottom stair

before I got out of bed and sneaked after

her. She padded into the kitchen, dressed in

slippers and the gray sweatshirt. What was

she doing? Getting a snack? Making

coffee? Moving closer, careful to stay out of

sight, I saw her go into the pantry. I was

amazed when she came out holding the

tooth bank. She unscrewed the rubber plug

on the bottom emptied some teeth into her

hand, and went out the back door.

I knew if I followed too closely she’d

catch me spying, so I eased out the front

door and ran around the house. The grass

was a cold wet shock to my bare feet.

Stealing from tree to tree, I saw Great

Grandma go into the garbage. A minute

later she came out carrying a trowel. Then

she went to the vegetable garden in back of

the house.

The whole thing felt like a dream but

my toes were so cold they were numb so I

knew it was real. I was about thirty feet

away, close enough to see her knee down

and start digging a hole in the garden. She

put one of the teeth into the hole, covered

it with dirt, and patted it down. She did the

same thing, three more times. Then, she

turned around and moved slowly back

toward the house.

I made myself wait five minutes,

then five more, before I went over to the

garden where she just planted our teeth. I

don’t what I expected to see. Finally, I went

inside and back to my bedroom.

That’s all that happened. There’s

really nothing more. But all that summer,

and for summers afterwards, I had the

keenest interest in that spot in the garden.

This may sound stupid but it’s the Gospel

Truth: every time I went past that spot I

would check to see if one of those teeth

had taken root in the soil, and started to

grow.

Day 5: Show Don’t Tell

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Use the writing strategy of “show don’t tell” to develop their ideas

fully.

Sentences for students to use

When we looked at all of those examples of personal narratives, one of the

things we saw good writers do is they “show don’t tell.”

Today, we will discuss how to show not just tell in our own personal

narratives.

Use your own writer’s notebook to share with students a place where you

show don’t tell. Ask students to tell you how you showed and didn’t just tell.

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

In partners, have students take a telling sentence and turn it into a piece of

writing that shows. For example, “The cafeteria was noisy” or “The dog was

angry.”

Today, when you write in your writer’s notebooks, I want you to think how

you can use show don’t tell to make your writing more powerful.

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Independent Writing

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Continue having students write their seed ideas in their own writer’s

notebooks.

Turn to a partner and share a place in your writing where you showed and

didn’t tell.

Day Six: Bring Your Characters to Life

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Identify how a mentor author uses dialogue and details to bring their

characters to life. Develop the characters in their narrative using

dialogue and details.

Excerpt from Flying Solo, by Ralph Fletcher

In previous lessons, we explored how narratives have characters.

In an exceptional piece of writing, the characters seem to lift off the page and

come alive like real people. We worry about them and care for them the way

we would a person we know.

Today we’re going to look at how to bring a character alive in a piece of

writing.

Let’s read an excerpt from Flying Solo, by Ralph Flectcher. Bastian is a sixth

grade student who is moving to Hawaii.

Ask students, “What do we learn about Bastian?”

Discuss.

Turn to a partner and share how the author brings him alive as a character.

Discuss. Students might mention the rude dialogue, especially Bastain using

the word peons, and the detail about how he gave other kids nasty

nicknames.

Bastian’s spoken dialogue, plus the information about all the unpleasant

nicknames he uses, allows us to hear the voice of the character. There are two

ways you can create voice in a character, even if the voice is very different

from your own.

Start an anchor chart labeled, “Strategies for Developing Characters.” Add the

two strategies discussed today, “Use dialogue” and “Add details about the

character.”

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Today, when you write, I want you to think about your characters. What can

you use, either dialogue or details, to make them seem realistic and

believable?

Independent Writing

Conference Questions:

When you reread your writing, what things do you notice that make

your characters come alive as real people or animals?

What details could you add or change to make a character seem more

realistic and believable?

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Turn to a partner and share one place where you added details or dialogue to

bring your character to life.

Excerpt from Flying Solo, by Ralph Fletcher

“My last day!” Bastian shouted as he entered the room.

“I thought you said Monday was your last day,” Karen said.

“My dad changed plans,” Bastian said. “Farewell, peons! I am

leaving you for the beaches of Hawaii!”

“You’ll look good in a hula hula skirt,” Jessica told him.

“You should talk, String Bean!” Bastian retorted. “Remember that

time you wore a dress? I laughed so hard I almost peed in my pants!”

“Shut up, Bastian,” Rhonda said.

Bastian had a mean streak, and Rachel didn’t trust him. He had

moved into town just before the beginning of sixth grade and

immediately made his presence felt by teasing kids in class. He invented

nasty little nicknames for just about everybody. Missy: Thunder Thighs.

Vicki: The Shrimp. Jessica: String Bean. He called Tommy Feathers The

Professor or, sometimes, Doctor Drool.

Day 8: Describe What your Characters Look Like

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Develop what their characters look like in their own writing.

Identify how a mentor author develops their character by describing

them.

“My Baby Sister”

Chart paper and markers

As a writer you want your readers to be able to picture your characters. It’s

easy to forget to do that because you have no trouble picturing a familiar

friend, relative, or pet while you’re writing. Remember your readers don’t have

those pictures in their mind.

We have discussed how we’d use dialogue and details to bring our characters

to life.

Today, we’ll discuss how author describe what their characters look like to

help their readers picture their characters in their mind.

Read “My Baby Sister” aloud.

Ask students, “What did you like about this description?”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Turn to a partner and tell how the author describes the baby.

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Think about your characters today when you write. Think about how you could

describe them do we could picture them. What details do you want to include?

I might talk to some of you about this during writing conferences.

Discuss. Kids might point out the comparisons, the humor, the anecdote at

the end of the paragraph. You might want to list their reactions on the chart.

Encourage kids to be as specific as possible. If someone says, “I like the

details,” you might reply, “Which ones stuck in your head?”

Writers who are good at describing their characters get in the habit of

observing them closely. You might need to go home and study your cat, or

your grandmother, to find more details to include.

Independent Writing

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Conference Questions:

What have you told us about the way your characters look that will

help us see them?

Are there places where you need to add visual details to help the

reader get a clearer picture of who you’re writing about?

Turn to a partner and share a place where you are working on developing

your character by using details, dialogue, or describing what they look like.

My Baby Sister

People laugh the first time they see my baby sister Anita. She’s cute, but funnylooking. Her perfectly round head is the size of a cantaloupe. She has blue eyes

and ears that stick out from her head like miniature TV dishes. Her mouth has

two teeth, one on top, one on the bottom, so when she smiles it looks like a jack

o’lantern. (She drools a lot.) But the funniest thing is her hair-she doesn’t have

any! Last week, Mom wanted Anita to wear a ribbon that matcher her dress.

Dad had to tape the ribbon to the top of her head! Then we held her up to the

top of her head! Then we held her up to the mirror so she could see the tapedon ribbon. Everybody was laughing like crazy because Anita though she looked

like the prettiest baby in the world.

Day 9: Using Dialogue to Bring Characters to Life

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Students will revise by telling what someone says, thinks or feels by

adding dialogue to elaborate the important scene.

Students will share their writing with a partner to help improve the

writing.

Personal narrative draft – student and teacher

Teacher’s sample revision (see example following lesson)

Chart paper and markers

We have been focused on ways to bring our characters to life. Another way to

make our writing more interesting is to stop and tell what a character is

thinking or feeling.

Teacher models revision using narrative draft.

Today we will revise adding dialogue.

Read aloud:

With each bubbly scrub she

whimpered softly.

Hmm. . . I think this would be a great point to zoom in on the moment.

Sadie hates baths. Now I am wondering what she might be feeling and

thinking.

She whimpered and seemed to be crying. I imagine if she could talk,

Sadie might share her feelings: This bath is torture!’

And her thinking: ‘What punishment for fun in the mud’.

Think aloud while adding dialogue and punctuation for quotation marks:

I’ll add this dialogue to show the words that Sadie is saying ‘inside’.

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

Quotation marks indicate exactly which words are being said. The

quotation marks always come right before the first word spoken. As in

any sentence, the first word is always capitalized and ends with a period,

question or exclamation mark. The quotation mark comes after the

ending punctuation mark.

Let’s write a dialogue sentence together. What might Sadie’s owner be feeling

giving the dog a bath.

Turn to a partner and come up with a dialogue sentence to tell what the

author might be thinking or feeling.

me…”

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Independent Writing

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Discuss students’ ideas.

Now reread an important event in your narrative. Watch for a place

you can add dialogue that tells what you or a character is thinking or

feeling. Remember to use quotation marks around the dialogue or

talking words.

Provide students with 10-15 minutes to apply the revision strategy.

Turn to a partner and share a place where you added dialogue to share what

your character is thinking or feeling.

As soon as we returned home Sadie had the soapiest bath ever!

I grabbed the tube of ‘Oh, So Shiny’ dog shampoo and plopped Sadie

into the bathtub. This was definitely NOT Sadie’s idea of fun. She

hated baths. She stiffened her skinny legs and her short tail hid

between her legs. Her ears hung sadly. With each bubbly scrub she

whimpered softly. What a mess! Muddy footprints, a grimy bathtub

and crumpled towels littered my bathroom floor. But finally, she was

our beautiful, shiny Sadie once again.

Day 10: Use Details to Bring the Setting Alive

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Name strategies to develop the setting in their own writing.

Identify how a mentor author uses the strategies to develop the

setting.

Write to develop their setting by using specific strategies.

You’ll need a text where the author develops the setting. Some

suggested mentor texts are Fox by Margaret Wild, Brave Irene by

William Steig, Very Last First Time by Jane Andrews, and any of the

descriptions of Camp Green Lake in Holes by Louis Sachar.

We discussed how narrative includes plot, characters, and setting. We’ve

identified how authors develop their characters using dialogue, details, and

description of what they look like.

Today, we’ll discuss how authors bring their setting to life.

What do we mean by setting?

Wait for response.

That’s right-the setting is the place where the story happens. Some stories

have more than one setting.

We’re going to be learning about the setting.

Read the story aloud.

How many settings are in this book?

Discuss and list students’ ideas on a chart.

How do the author and illustrator bring alive the settings in this book?

Discuss.

Create an anchor chart titled “Developing Setting.” Add the following

strategies as they are discussed in the lesson:

Where will your story take place?

What does that place look like?

How does the place sound, feel, and smell?

How will your character be affected by the setting?

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Today, when you’re writing, I want you to think about the setting for your

story. Make sure you’ve described the setting using vivid details. Use your five

senses. What does the place sound and smell and feel like? How will your

characters be affected by the setting?

Independent Writing

Conference Questions:

What is the setting for your story? What details have you used to

bring that place alive?

Have you considered ways that your setting could have an impact on

the plot or the characters?

Turn to a partner and share which strategies you are using to develop the

setting in your narrative.

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Day 11: Make a Plan

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Outline a plan for their writing piece.

Discuss strategies for planning out for writing.

Your writer’s notebook with example of plan

(Note: You will want to have students prior to this lesson chose seed entries

they’d like to write into a full personal narrative. Place a sticker on the story

they will develop during the next couple of weeks.)

By now you have done lots of different kinds of writing in your notebooks.

You’ve doodled and sketched, wondered and reacted. You’ve gathered lists,

artifacts, and random facts.

These entries are like chicks in an incubator. There comes a time when the

chick is ready to leave the safety of the incubator and go out into the world.

The same is true with your notebook. By now you may be ready to take an

entry, or several entries, and craft a finished story.

Today, we’ll work on writing a plan for the seed entry you have chosen to

develop into a full piece.

Share a plan from your writer’s notebook. (Note: Share a list of events and

then also a timeline.) Explain that a plan doesn’t have to be complicated.

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Ask a student to tell about their seed entry. Use the student example to

outline and model a plan with the class as an example.

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Think about how you can use your notebook to make a plan for writing you

want to finish. Once you know what you want to write, try to envision the

finished piece. What will it include? How do you want to organize it? What

should come first, in the middle, at the end? You may find that you need to

make more than one plan until you’ve for one that feels right.

Independent Writing

Note: We can sometimes overuse prewriting. If kids spend too much time

completing webs, outlines, story maps, and graphic organizers, they’ll have

little energy left to actually write the finished piece. Remember: the

prewriting should serve the writer, not the other way around.

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Turn to a partner and share your plan for writing your personal narrative.

Day 12: Using Transition Words

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Combine provided sentences using time transitions.

Incorporate time transitions into their own work to help their

narratives move along.

Sentences prepared for students to revise with transitional words.

Additional mentor text recommended for highlighting transition words and

phrases:

My Great Aunt Arizona by Gloria Houston

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney

I have noticed some of you use some words such as “first, second, last, finally”

in your writing. These are important clue words to your readers.

During the school day I often let our class know that something new is

about to happen. You have heard me say, ‘It’s time for reading’, or ‘Let’s

line up for recess,’ when we change from one activity to another.

Writers do the same for their readers. Writers use special transition words to

let the reader know a change in time or place is about to happen.

Tell students that there are different kinds of transition words. Explain that

one kind of transition word is time transitions, which helps the reader know

the order of events in a story.

Discuss how using different transition words changes the meaning of a

sentence. Put the following 2 sentence strips in the pocket chart:

Dad and I went fishing.

Mom made our lunch.

Show students how you can connect the sentences by adding transition

words. For example:

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Dad and I went fishing. / Meanwhile / Mom made our lunch.

After / Dad and I went fishing, / Mom made our lunch.

Before / Dad and I went fishing, / Mom made our lunch.

Dad and I went fishing / after / Mom made our lunch.

While / Dad and I went fishing, / Mom made our lunch.

Discuss how the different transition words change the meaning of the

sentences by changing the sequence (order) of events.

Put the following 3 sentence strips up on the pocket chart.

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

o

o

o

Marty saw the puppy.

He recognized it.

He picked it up.

Give 3 student volunteers three cards with 3 transition words on them (First,

Then, After that). Tell students that the transition words on the cards will help

them put the sentences in the correct order:

First, Marty saw the puppy. Then he recognized it. After that, he picked it up.

Give students other transition words on cards and ask them how the words

change the meaning of the sentences:

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Independent Writing

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

After Marty saw the puppy, he recognized it, and he picked it up.

As soon as Marty saw the puppy, he recognized it and immediately picked it

up.

As writers, all year long, you’ll use transition words to help organize your

writing.

Have students select a draft from their writing folder. Have them highlight the

transition words they used. Then have them choose a paragraph to revise by

adding 3-5 transition words.

Turn to a partner and share your revised paragraph.

Transition Words List

After

In the meantime

Afterward

Later As

soon as

Next At

first

Soon At

last

When

As a result

When suddenly

Before

We had just Before

long

It was not long

Finally

In the afternoon For a

long time

Until

Day 13: Write a Lively Lead

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Identify strategies for writing leads.

Write several leads for their story.

“Little Red Riding Hooks” Handout (You may want to limit the

number of strategies to three for students to try. Throughout the

school year additional strategies can be added.)

We now have plans for what we’d like to write. We need to continue

exploring how we’ll organize our writing. A lead is an important part of

organization.

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Today we’re going to talk about the lead.

Does anyone know what a lead is?

Discuss.

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

A lead is the beginning of a piece of writing. The purpose f a lead is to set the

mood, or tone, for the writing. A strong lad engages us as readers, draws us

in, makes us want to continue reading.

Let’s look at some strategies to start out writing.

All of you know the story of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Let’s look at some

examples of how we might start that familiar story.

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Create an anchor chart of the strategies identified through the discussion.

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

We’re going to be looking at different kinds of leads this year. This is just one,

but it’s worth looking at, and learning from.

Independent Writing

Have students write several leads for their story using some of the strategies

identified in class.

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Turn to a partner and share one strategy you might use to start a lead.

Today, I want you to think about your lead, both when you write and when

you reread what you’ve written. Write the kind of lead that sounds like you

and that will grab the reader’s attention.

Turn to a partner and share some of your leads.

Consider collecting leads from students that can serve as good examples for

students.

This writers’ handout was designed to accompany one of WritingFix’s on-line, interactive writing prompts.

Little Red Riding Hooks…

From the amazing classroom of Dena Harrison, Mendive Middle School

Great alternatives to introductions, hooks, and leads

“Once upon a time, there lived a little girl with a red riding

hood…” KIND OF A BORING, CLICHÉ INTRO!

There are more interesting ways to start off this famous story. Below are

eight techniques to consider:

Technique one: Start with a short (four- or fiveword maximum), effective sentence:

Her hair shone gold.

Technique three: Start with an interesting

question for the reader to ponder:

Who could have thought that

a simple trip to Grandma’s

house could end in tragedy?

Technique five: Start with a riddle:

Who has big eyes, big teeth and

is dressed in Grandma’s clothes?

Yes, you guessed it, the Big Bad

Wolf.

Technique seven: Capture a feeling or emotion:

You might be surprised to learn

that a little girl couldn’t

recognize her own

grandmother.

Technique two: Start with an interesting

metaphor or simile:

The wolf was a tornado,

changing the lives of all who

crossed his path.

Technique four: Start with a subordinate clause

or other complex sentence form:

Though the road to Grandma’s

house was spooky, Red skipped

along with an air of confidence.

Technique six: Fill in these blanks: “

kind of

who/that

”

was the

Little Red was the kind of girl

who thought wolves would

never bother her.

Technique eight: Use a string of adjectives:

Tall, dark, and with an air of

confidence, the woodsman

entered the house.

©2006 Northern Nevada Writing Project. All rights reserved.

This resource comes from the best website for writers and writing teachers: http//writingfix.com and http://writingfix.org

This writers’ handout was designed to accompany one of WritingFix’s on-line, interactive writing prompts.

Novel Openings: What Makes These Good?

Here are the openings from 20 excellent novels. Many of them are already classics. Have your

students discuss why they might have impact on a reader.

1. Call me Ishmael. —Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (1851)

2. A screaming comes across the sky. —Thomas Pynchon, Gravity's Rainbow (1973)

3. It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. —George Orwell, 1984

(1949)

4. I am an invisible man. —Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

5. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of

foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it

was the season of

Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.

—Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two

Cities (1859)

6. The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new. —Samuel Beckett, Murphy (1938)

7. Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a

mirror and a razor lay crossed. —James Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

8. Through the fence, between the curling flower spaces, I could see them hitting. —William

Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury (1929)

9. Every summer Lin Kong returned to Goose Village to divorce his wife, Shuyu. —Ha Jin,

Waiting (1999)

10. All this happened, more or less. —Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969)

11. They shoot the white girl first. —Toni Morrison, Paradise (1998)

12. Dr. Weiss, at forty, knew that her life had been ruined by literature. —Anita Brookner, The

Debut (1981)

13. Ships at a distance have every man's wish on board. —Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were

Watching God (1937)

14. It was the day my grandmother exploded. —Iain M. Banks, The Crow Road (1992)

15. It was a pleasure to burn. —Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

16. In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I've

been turning over in my mind ever since. —F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

17. It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I

didn't know what I was doing in New York. —Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar (1963)

18. He was an inch, perhaps two, under six feet, powerfully built, and he advanced straight

at you with a slight stoop of the shoulders, head forward, and a fixed from-under stare

which made you think of a charging bull. —Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim (1900)

19. In the town, there were two mutes and they were always together. —Carson McCullers, The

Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940)

20. The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army

stretched out on the hills, resting. —Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (1895)

Three powerful “hooks” from young adult novels:

“Where's poppa going with the axe?" said Fern to her mother as they were setting

the table for breakfast. —E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web (1952)

There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it. —C. S.

Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were

perfectly normal, thank you very much. —J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s

Stone (1997)

©2006 Northern Nevada Writing Project. All rights reserved.

This resource comes from the best website for writers and writing teachers: http//writingfix.com and

http://writingfix.org

Day 15: Come Up with the Right Ending

Focus Lesson Topic

Materials

Connection

Connect the lesson to

what students already

have learned or

something specific that

you have noticed.

“Yesterday we learned

how to…”

“I have noticed…”

“Many of you have

asked…”

Teaching (I do!)

Tell them what you will

reach today.

“Today I am going to

teach you how to…”

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

Write several ending for their story.

Identify strategies for writing endings.

Markers and Chart Paper for Anchor Chart

Mentor text with opening and ending to share with students

We’ve been discussing and writing leads for our narratives. We identified

strategies for developing leads.

Today, we’ll discuss endings. Endings are important, too. Have you ever

watched a movie or TV show that started out strong but had a lousy ending/

Have you ever read a book that did that?

Discuss.

Show them exactly how

to do it.

“Watch me do it…” or

“Let’s take a look at

how (author) does this

when s/he writes…”

Active Engagement

(We do!)

Ask them to try it with

you, or with a partner,

for a few minutes.

“Now you all try it with

me…”

Send Off (For

Independent Practice)

Link (You do!)

“So for the rest of your

lives I want you to

remember that good

writers…You might

want to try it today or

some other time and

see if it helps you…”

Think about it: the ending is the last thing that will linger in the ear and mind

of your reader when he or she has finished your story. You want to leave them

with an ending that’s right for what you have written. Let’s take a look at

some endings.

Share endings with students from mentor texts. Identify the strategy the

author used to end their piece. List strategies on anchor chart.

Turn to a partner and share which strategy you’ll try for your writing.

Today’s challenge is to try several of the strategies for endings for your piece.

Independent Writing

Group Wrap Up

(Share)

“Did anyone try out

what was taught

today?”

Students should write several endings for their piece in their notebooks.

Conference Questions:

Have you thought about your ending?

What ending would fit best with the story you’re working on?

Turn to a partner and share the strategy you used and your ending.

Anchor Chart: Designing an Ending

The ending is the last thing that will linger in the ear and mind of the

reader.

Choices for endings:

Splashy

Funny

Sad

Small Detail

Surprise

Circular

Factual

Quotation

Literary Beginnings and Endings

Beginning:

Magnus Bede, the famous alchemist, and his happygo-lucky wife, Eutilda, thought they had a

harmonious family. But their older son, Yorick,

considered little Charles a first- rate pain in

the pants, always occupied with something silly.

Ending:

The two brothers sincerely appreciated each other

now. Except when they were having a fight.

Steig, W. (1996). The Toy Brother. New York: HarperCollins.

-----------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

She could have picked a chiming clock or a

porcelain figurine, but Miss Bridie chose a shovel

back in 1856.

Ending:

She could have had a chiming clock or a porcelain

figurine, but Miss Bridie chose a shovel back in

1856.

Connor, L. (2004). Miss Bridie Chose a Shovel. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

---------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

Winter is coming.

Ending:

Summer is coming.

Arden, C. (2004). Goose Moon. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Beginning:

Ruthie Simms didn’t have a dog. She didn’t have a

cat, or a brother, or a sister. But Jessica was

the next best thing.

Ending:

Ruthie Simms didn’t have a dog. She didn’t have a

cat, or a brother, or a sister. But Jessica was

even better.

Henkes, K. (1989). Jessica. New York: Penguin.

---------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

Miss Elizabeth felt troubled.

Ending:

And Miss Elizabeth rocked and rocked and rocked.

Gray, L. (1993). Dear Willie Rudd. New York: Simon & Schuster.

---------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

Ending:

This is the pot that Juan built.

The beautiful pot that Juan built.

Andrews-Goebel, N. (2002). The Pot That Juan Built. New York:

Lee & Low Books.

--------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

One wintry day I made a snowman, very round and

tall.

Ending:

So if your snowman’s grin is crooked, or he’s lost

a little height, you’ll know he’s just been doing

what snowmen do at night.

Buehner, C. (2002). Snowmen at Night. Buehner, M. (illus.). New

York: Putnam.

-------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

Two men walked into the rain forest.

Ending:

Then he dropped the ax and walked out of the

rain forest.

Cherry, L. (1990). The Great Kapok Tree: A Tale of the

Amazon Rain Forest. San Diego: Harcourt Brace.

--------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

When the eggs hatched, the little crocodiles

crawled out onto the riverbeach. But

Cornelius walked out upright.

Ending:

Life on the riverbeach would never be

the same.

Lionni, L. (1983). Cornelius. New York: Alfred A.

Knopf.

------------------------------------------------------------Beginning:

This is the great Kapiti Plain,

All fresh and green from the African rains,

A sea of grass for the ground birds to nest in,

And patches of shade for wild creatures

to rest in…

Endings:

So the grass grew green and the cattle

fat, And Ki-pat got a wife and a little

Ki-pat—.

Who tends the cows now, and shoots