The initiation of the campaign for the women

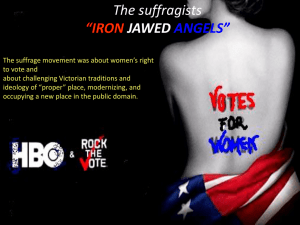

advertisement

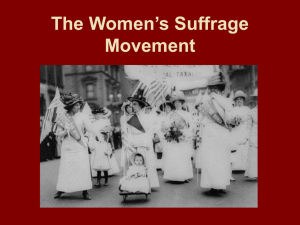

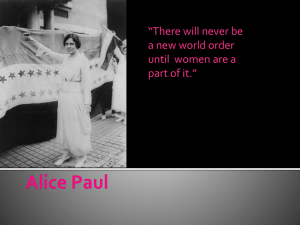

The initiation of the campaign for the women’s suffrage movement in the United States dates back to the decades before the American Civil war in 1861. During that time, most states extended the franchise to all white men, regardless of how much money or property they had1. American women were begging to challenge the “cult of true womanhood”2, the idea that a true woman was a worshipful, submissive wife and mother concerned only with home and family. There was a general belief at the time was that the female mind was inferior. The argument for women’s suffrage was that women did not make the laws, but still had to obey them like children. In 1948 a group of abolitionist activists – mostly women but some men, gathered to discuss the problem of women’s rights in Seneca Falls, New York3. The Seneca Falls Convention was perhaps the first big step in the social movement as the first formal demand was issued by American women. Suffragists became active in every state and territory, but were most successful in the west as they were trying to attract white settlers4. Wyoming would become the first state to grant suffrage in December of 1890 but the most significant progress occurred between the years of 1912 and 1920 with some inspirational women leading the way. The Seneca Fall Convention was the first step of the suffrage movement that took just over seven decades before the United States Congress passed the 19th amendment - granting women the right to vote. War and anti-suffragist movements were the biggest obstacles, but the fight would be led by educated women and inspirational women – one of them being Alice Paul. She was born in Moorestown, New Jersey in 1885 and received a degree from Swarthmore 1 History.com Staff, “The Fight for Women’s Suffrage,” A+E Networks (2009), http://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/the-fight-for-womens-suffrage 2 History.com Staff, “The Fight for Women’s Suffrage”. 3 History.com Staff, “The Fight for Women’s Suffrage”. 4 Zecker, Robert M., “Women’s Suffrage”, Lecture, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, January 14, 2014. College before living in England while attending the University of Birmingham where she pushed for women's voting rights5. She returned to America in 1910 and received a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1912. Alice Paul began her fight for women’s suffrage in America as a member of the “National American Women Suffrage Association” where she served as the chair of its congressional committee; however she criticized their policies6. As a result of her frustration, Paul left the NAWSA and formed the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage with a women from Brooklyn, New York – Lucy Burns. Lucy Burns was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1879. She was a very educated woman attending schools like Columbia University, Vassar College, and Yale University before moving to the United Kingdom to study English at Oxford University7. Lucy Burns met Alice Paul at a London police station after both women had been arrested for demonstrating. They discussed their suffrage experiences in the UK and America and bonded over their frustration with the inactivity and ineffective leadership of the American suffrage movement by Anna Howard Shaw8. The two women became good friends as they had similar passions and fearlessness in the face of opposition. Feminist struggle for equality in the UK inspired Burns and Paul to continue the fight in the United States in 1912. Upon their return to America, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns met a labor lawyer from Brooklyn, New York by the name of Inez Milholland. She was blessed with all the advantages a 5 "Alice Paul," The Biography Channel website (2014), http://www.biography.com/people/alice-paul-9435021 "Alice Paul," The Biography Channel website. 7 Bland, S.R. “‘Never Quite as Committed as We’d Like’: The Suffrage Militancy of Lucy Burns’”, Journal of Long Island History (1981). 8 Bland, S.R. “‘Never Quite as Committed as We’d Like’: The Suffrage Militancy of Lucy Burns’”. 6 woman born in 1886 could ever desire; intelligence, wealth, and beauty9. Her father, John Milholland was a religious man who supported equal rights for women and African Americans and was a founder of the “National Association for the Advancement of Colored People”10. Inez Milholland received her BA in 1909 and applied to law school at Oxford, Cambridge, Columbia and Harvard – all whom denied her because she was female. She attended law school at New York University11. Leaders of the suffragist movement like Alice Paul and Harriot Stanton Blatch appropriated the dominant gender ideology of the early 20th century and provided a symbol of beauty, elegance, and grace in the face of the negative imagery the anti-suffrage movement generated. They used Inez Milholland’s image to the movement’s advantage. She provided the movement with a representation that undermined the association of female political participation with masculine women and gender transgression12. Milholland was closely allied to Harriot Stanton Blatch and the New York Wing but she was most often associated with Alice Paul and the Congressional Union13. She became one of the movement’s most effective promoters and made her most memorable appearance leading the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington D.C., wearing a crown and a long white cape while riding atop a large white horse14. Description: The picture to the left shows Inez Milholland wearing a white cape seated on a white horse as she leads the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade on March 3, 1913, in Washington, D.C. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress. 9 Nicolosi, Anne Marie, “’The Most Beautiful Suffragette’: Inez Milholland and the Political Currency of Beauty”, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, (2007). 10 Nicolosi, Anne Marie, “’The Most Beautiful Suffragette’: Inez Milholland and the Political Currency of Beauty”. 11 Nicolosi, Anne Marie, “’The Most Beautiful Suffragette’: Inez Milholland and the Political Currency of Beauty”. 12 Nicolosi, Anne Marie, “’The Most Beautiful Suffragette’: Inez Milholland and the Political Currency of Beauty”. 13 Nicolosi, Anne Marie, “’The Most Beautiful Suffragette’: Inez Milholland and the Political Currency of Beauty”. 14 Perry, Marilyn Elizabeth, “Boissevain, Inez Milholland” American National Biography, (2000). On March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the National American Women Suffrage Association sponsored the first national women’s suffrage parade15. Alice Paul and Lucy Burns organized thousands of women from across the United States and of all ages and social classes to march down Pennsylvania Avenue through the capitol city demanding the right to vote. African-American women were asked to march separately at the end of the march, because white suffragists were concerned about losing the support of southern voters. The date of the parade was strategic as the official program stated that the march was in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women were excluded. Teddy Roosevelt's Progressive Party became the first major political party to pledge itself to the task of securing equal suffrage to men and women alike, but the Progressives lost the election16. After a good beginning, the marchers encountered mostly male crowds on the street that should have been cleared for the parade. The marchers were harassed while attempting to squeeze through, and the police were sometimes of little help, or even participated in the harassment. After the parade, over 200 people were treated for injuries at local hospitals17. Senate hearings, started three days after the march, and lasted until March 17, which resulted in the replacement of the District's superintendent of police18. NAWSA praised the parade and Alice Paul's work on it, saying "the whole movement in the country has been wonderfully Moore, Sarah J., “Making a Spectacle of Suffrage: The National Women Suffrage Pageant, 1913”, Journal of American Culture 16 Harvey, Sheridan., “Marching for the Vote: Remembering The Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913”, Library of Congress, (2001). 17 The Washington Post, March 5, 1913. 18 Suffrage Parade: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, Government Printing Office, (1913). 15 furthered by the series of important events which have taken place in Washington, beginning with the great parade the day before the inauguration of the president"19. The 1913 Washington march came at a time when the suffrage movement badly needed new way to capture public and press interest – an infusion of strength. Women had been struggling for the right to vote for more than sixty years, and although progress had been made in recent years on the state level with six western states granting women suffrage, the movement had stalled on the national level20. About two weeks after President Wilson’s inauguration, the President received a suffrage delegation led by Alice Paul, who chose to make the case for suffrage verbally. President Wilson replied that he had never given the subject any thought, but that it “will receive my most careful consideration.21”Anna Howard Shaw, president of NAWSA had no knowledge of the meeting and complained to Alice Paul for not including her. The reason for Anna Howard Shaw’s absence was because the leadership of the NAWSA was not interested in changing their state-by-state strategy and rejected the idea of holding a campaign that would hold the Democratic Party responsible. Alice Paul and her Washington supporters soon established their own, independent suffrage party, the National Woman's Party, to work solely on the passage of a constitutional amendment22. Harvey, Sheridan., “Marching for the Vote: Remembering The Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913”, Library of Congress, (2001). 20 Harvey, Sheridan., “Marching for the Vote: Remembering The Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913”. 21 Harvey, Sheridan., “Marching for the Vote: Remembering The Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913”. 22 Lunardini, Christine A, “From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928”. New York: New York University Press, (1986). 19 https://socialstudiesdiscussion.wikispaces.com/file/view/Alice+Paul+50+facts.pdf Making a Spectacle of Suffrage: The National Woman Suffrage Pageant, 1913 Sarah J. Moore the idea that the only “true” woman was a pious, submissive wife and mother concerned exclusively with home and family. Put together, all of these contributed to a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a woman and a citizen in the United States.