The North Thanet Coast

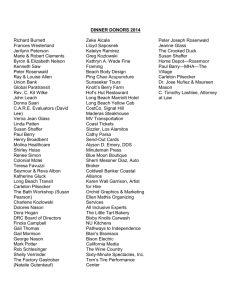

advertisement