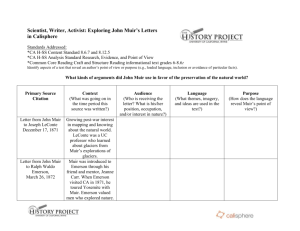

A Brief Biography

advertisement

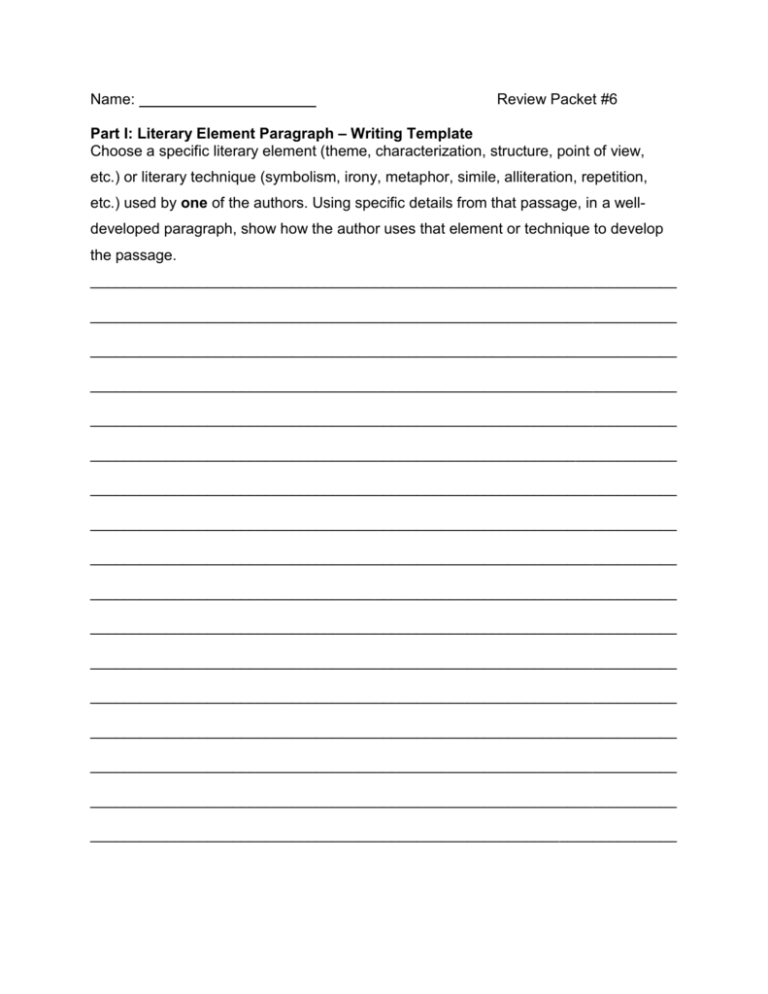

Name: Review Packet #6 Part I: Literary Element Paragraph – Writing Template Choose a specific literary element (theme, characterization, structure, point of view, etc.) or literary technique (symbolism, irony, metaphor, simile, alliteration, repetition, etc.) used by one of the authors. Using specific details from that passage, in a welldeveloped paragraph, show how the author uses that element or technique to develop the passage. ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ “A Noiseless Patient Spider” By Walt Whitman A noiseless, patient spider, I mark'd, where, on a little promontory, it stood, isolated; Mark'd how, to explore the vacant, vast surrounding, It launch'd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself; Ever unreeling them--ever tirelessly speeding them. And you, O my Soul, where you stand, Surrounded, surrounded, in measureless oceans of space, Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing,--seeking the spheres, to connect them; Till the bridge you will need, be form'd--till the ductile anchor hold; Till the gossamer thread you fling, catch somewhere, O my Soul. “Revelation” Robert Frost We make ourselves a place apart Behind light words that tease and flout, But oh, the agitated heart Till someone really find us out. 'Tis pity if the case require (Or so we say) that in the end We speak the literal to inspire The understanding of a friend. But so with all, from babes that play At hide-and-seek to God afar, So all who hide too well away Must speak and tell us where they are. Part II: Grammar – The Danger of Mis-Punctuation Donald J. Sobol’s book Encyclopedia Brown and the Case of the Missing Handprints contains the story of Tyrone, a hopeless romantic, who writes the following love letter to his would-be girlfriend, Adorabelle: How I long for a girl who understands what a true romance is all about. You are sweet and faithful. Girls who are unlike you kiss the first boy who comes along, Adorabelle. I’d like to praise your beauty forever. I can’t stop thinking you are the prettiest girl alive. Thine, Tyrone. The trouble is, Tyrone dictates his letter over the phone to Adorabelle’s young sister, who doesn’t understand how punctuation works. She places punctuation marks in all the wrong places, so Adorabelle is furious when she reads the letter. Your Task: Repunctuate Tyrone’s letter in such a way that it becomes insulting. ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Part III: SAT - Vocabulary Skills: Analogies DIRECTIONS: For each of the following items, choose the lettered pair of words that expresses a relationship that is most similar to the relationship between the pair of capitalized words. 1. INGENIOUS : SKILLFUL :: A rich : wealthy B stubborn : easygoing C irritated : pleased D sweet : sour 2. MALODOROUS : SKUNK :: A robin : bird B deceitful : cheater C fair : tyrant D teacher : faculty 3. ABOMINABLE : DISGUSTING :: A ferocious : tame B accident : blame C mistaken : correct D horrifying : scary 4. EULOGY : SPEECH :: A envelope : letter B comedy : play C death : burial D writer : typist 5. AUSTERE : LUXURIOUS :: A harsh : severe B secure : safe C restful : vacation D elegant : plain Part IV: Non-Fiction—Close Read A Brief Biography-John Muir In the spring of 1868, a young man came to Yosemite and changed the world. Muir had just turned 30 that year. His first 11 years were spent in Dunbar, Scotland. The next 11 he spent in the backwoods of Wisconsin, working through the daylight hours, clearing the forest, holding a plow to a straight furrow behind a team of oxen, digging wells through hard bedrock, and taking an adult’s part in subduing wild nature. Years later, in The Story of My Boyhood and Youth, he stressed the rigors of his childhood, but he seemed to feel that his strenuous years in Wisconsin prepared him well for his later wilderness ramblings. He also prepared throughout his childhood for his life as a naturalist by a close attention to the wonders of nature. Everything, it seemed, drew his eye and his mind, and all creatures drew his sympathy, whether the mice that ate the grain he had wrung from the earth by the sweat of his brow or the intelligent old ox Buck, who figured out how to open pumpkins to feast on the succulent inner flesh. As a teenager, he had no time for school and little opportunity for formal study. Yet his mind hungered for knowledge. When his father grudgingly gave permission for him to rise before the rest of the family to read, he took to rising at one in the morning. He wrote, “I had gained five hours, almost half a day! ‘Five hours to myself!’ I said. ‘Five huge, solid hours!’ I can hardly think of any other event of my life, any discovery I ever made that gave birth to joy so transportingly glorious as the possession of these five frosty hours.” Over the next three years he worked as a mechanic and took several short wilderness trips. Much of the Civil War he spent in Canada, perhaps to avoid the draft, though that is far from certain. What is certain is that in 1867 a momentous accident changed his life. He was adjusting some machinery with a file when his hand slipped. A point of the file pierced one eye. He lost the use of that eye. The other soon went dark in sympathy. It was the darkest moment of his life for his spirit, as well as his sight. As his sight gradually returned, over a period of months, he felt that he had been re-born. He resolved to spend the rest of his life immersed in the sights that had been denied him in his darkened sickroom — the forests, fields, lakes and mountains of pure, unspoiled nature. His first great wilderness adventure was a thousand mile walk from Louisville, Kentucky to Savannah, Georgia. From there, he hoped to travel to the headwaters of the Amazon and work his way to the sea. But a case of malaria laid him low in Florida and, by a wandering course, he ended up in San Francisco in March, 1868. He inquired the nearest way out of town. “‘But where do you want to go?’ asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. ‘To any place that is wild,’ I said.” So he went to Yosemite. The next six years brought about another transformation. His first summer in Yosemite, he worked as a shepherd. Then he ran a sawmill near the base of Yosemite Falls. But all the time he was working, he was studying nature, the great truths that, he said, were written in “magnificent capitals” — the awesome stones of the Sierra Nevada. He became a guide for some of the most famous of Based on this information, why would Chris McCandless be compared to Muir? Define succulent Based on the fact that Muir is a naturalist, why was this the darkest moment for him? How is his behavior similar to McCandless’? Yosemite’s visitors, including one of his idols, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson tried to entice Muir away from Yosemite, telling him the world was waiting to hear him teach the lessons he had learned. But Muir chose to follow the ideal Emerson had set forth in “The American Scholar.” He stayed in his mountains, working, studying and learning. Eventually, he did leave the Valley. First for only a few months at a time. He would live with friends in San Francisco or Oakland and write about his glorious mountains, the scenery that drew tourists and the science behind the scenery. Gradually, he spent more time in the Bay Area and less time in Yosemite. In 1880, he married and moved to Martinez, California, 35 miles from San Francisco. He still traveled, sometimes to Yosemite, several times to Alaska. But the decade of the 1880′s saw him mostly in Martinez, applying his love of plants and fecund imagination to the task of raising Bartlett pears and Tokay grapes. He became fairly wealthy, but seemingly discontented. Each trip to the mountains presented him with more proof that, unless something was done, the glorious wilderness he had found in 1868 would soon be only a memory. In 1892 the Sierra Club was created, with Muir as President, apostle, guide, and inspiration. The purpose of the Club was to preserve and make accessible the Sierra Nevada. The summer of 1901, ninety-seven “Sierrans” including Muir and his two daughters assembled in The Valley and trekked to Soda Springs for a month of hiking, peak climbing, campfire entertainment and education. Thirty years later, twenty years after Muir’s death, another woman wrote of her own experiences on a High Trip. “Never had I really understood John Muir’s ecstasy until I wandered through this little valley.” That “ecstasy” was exactly what Muir found most lacking in California, even among his fellow “preservationists.” “The love of Nature among Californians is desperately moderate; consuming enthusiasm is almost wholly unknown.” It was this ecstasy in Nature that distinguished Muir from most other preservationists and it was this very emotionalism that made him so attractive to the women he met as well as others who weren’t embarrassed by their emotional response to Nature. Over the years, Muir developed from a guide for select individuals to a guide for the Sierra Club to a guide for the whole nation. Not just to Yosemite or any other specific place, but to the inner regions of the emotional response to Nature, especially Wild Nature. Muir died of pneumonia in a Los Angeles hospital in January, 1914. It was a unexpectedly prosaic end for a man who had repeatedly faced death on rocky crags and icy glaciers, who braved Alaskan storms with a crust of bread in his pocket. In the years since, his legend has grown. In 1976, the California Historical Society voted him “The Greatest Californian.” But perhaps the greatest tribute ever given to Muir took place in a private conversion between two great contemporary mountaineers. Galen Rowell once asked Rheinhold Messner why the greatest mountains and valleys of the Alps are so highly developed, why they have hotels, funicular railways, and veritable cities washing up against sites that, in America, are maintained relatively unencumbered by development. Messner explained the difference in three words. He said, “You had Muir.” Define fecund Define prosaic Explain the impact Muir has had on American wilderness.