File - MiSuk Robinson Professional Nursing Portfolio

advertisement

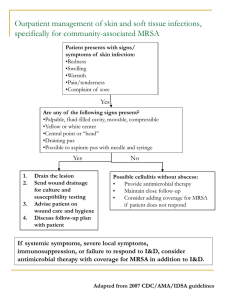

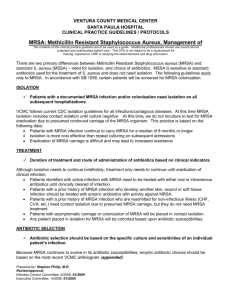

Evidence-based Practice Paper: Contact Isolation for MRSA 1. Purpose (all reasoning has a purpose) Currently all surgical patients with a previous history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are placed in contact isolation. Is this a necessary practice if patients do not have an active MRSA infection? Increasing prevalence of community acquired MRSA) and MRSA colonization has presented new challenges in healthcare. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) 2007 guidelines recommend that all patients with a previous history of positive MRSA culture be kept in contact isolation for every hospital admission (CDC, 2012). Some research indicates that contact isolation has not reduced the acquisition rate of MRSA in the hospital from MRSA colonized patients (APIC, 2007). Research has shown that patients often feel stigmatized when placed in isolation (Pope, D., Morrison, G., Hansen, T., 2009). 2. Questions at issue or central problem (all reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, solve some problem). Do patients have to remain in contact isolation every time they are hospitalized if they have a past history of a positive MRSA culture? What happens if a patient has been mistakenly identified? How does the patient remove the MRSA label from his electronic chart? Is routine MRSA screening of all surgical patients feasible to remove the contact isolation precaution without increasing the risk of hospital acquired MRSA? 3. Point of view (all reasoning is done from some point of view; think about the stakeholders). Hospital acquired MRSA infections account for more than 50% of Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial infections since 1999 (Seigel, J.D., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., 2006). This increases the risk for patient mortality, length of hospital stay, and treatment costs. The implementation of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) value based incentive payment will decrease or refuse payment to healthcare institutions in cases of nosocomial infection (HCAHPS, 2010). Patients who do not have a current MRSA infection do not understand why they are in contact isolation. The policy is not consistent within area hospitals who do not utilize electronic charting and electronic flagging of MRSA. Patients feel stigmatized when in contact isolation and report decreased satisfaction with hospital encounter (Barrat, R., Shaban, r., Moyle, W. (2011). This will also affect hospital reimbursements due to HCAHPS (HCAHPS, 2011). Poor compliance with contact isolation policy by healthcare providers may contribute to lack of consistency in patient perception of contact isolation procedures. There is increase cost to the hospital in supplies, increase nursing time to take care of isolation patients, and environmental cleaning. 4. Information (all information is based on data, information, evidence, experience, research). Klein and Smith (2007) reported an estimated cost of 9.7 billion dollars to treat patients with MRSA associated complications and 6,639 deaths attributed to MRSA in 2005. Current CDC guideline regarding previous history of MRSA is to implement contact isolation for every hospital admission (CDC, 2011). For hospital acquired MRSA contact isolation may be discontinued when 2 cultures are negative after all antibiotic therapy has been stopped (CDC, 2011). There are no guidelines for routine screening of patients colonized with MRSA. Routine decolonization of MRSA for elective surgical procedures has had varying success of up to 80% (Dow, G., Field, D., Mancuso, M., Allard, J., 2010). Patients would undergo an initial nasal swab culture. If the culture was positive for MRSA colonization then the patient would start Mupirocin nasal ointment twice a day for 10 days. A second nasal swab culture is then taken. If it is negative then the patient would not need to be in contact isolation. Most studies also include a Chlorihexidine bath once a day for 5 days prior to surgery (APIC, 2007). Compliance with MRSA precautions averages 28% (Pope, D.M., Morrison, G.A., Hansen, T.S., 2009). Many healthcare providers’ perceptions of best-practice do not include strict hand hygiene for MRSA precaution (Henderson, D.K., 2006). Patients report negative association with being in contact isolation: feelings of stigmatism, decreased socialization, limited independence, anger, frustration, and fear (Barrat, R., Shaban, R., Moyle, W., 2010). A study by Abad, Fearday, and Safdar (1995) indicated that patients were more likely to be depressed or anxious and more likely to have an adverse event when placed in isolation. 5. Concepts and ideas (all reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas). MRSA related complications have a tremendous impact on patient safety and satisfaction. Current guideline by the CDC supports contact isolation protocol for anyone with a past history of MRSA and does not recommend routine testing (CDC, 2011). Although a patient may have been successfully treated and is now negative the guideline dictates that this patient be placed in isolation for every hospital admission for the rest of their life. As more people develop community acquired MRSA and become colonized the healthcare industry will need to address the feasibility of keeping people in contact isolation. Routine testing of elective surgical patients would help verify current MRSA status (Hardy, K.J., Szcepura, A., Davies, R. et al., 2007). If cultures are negative then the patient would not need to be placed in contact isolation. If the cultures were positive for colonization then there would be the option to treat in an attempt to decolonize with Mupirocin prior to surgery. If the decolonization was effective then again the patient would not need to be placed in contact isolation 6. Assumptions (all reasoning is based on assumptions-beliefs we take for granted). Patient safety is the priority of all healthcare providers. Staff are expected to follow hospital policies and utilize best-practice to limit nosocomial infections. Noncompliance issues may be due to lack of education in regards to the importance of strict hand hygiene. Most hospital acquired MRSA can be attributed to cross contamination by healthcare providers’ hands (Henderson, D.K., 2006). Lack of adequate supplies (isolation supplies, hand sanitizer, bacteriostatic wipes, etc.) may hinder strict adherence to support isolation precautions. Environmental cleaning policies may also need to be re-evaluated for MRSA exposure. Implementation of active surveillance cultures (ASC) would help identify current MRSA status in patients with a previous history of MRSA. If cultures are negative then patients would not need to be placed in isolation for a hospital admission. This would increase patient satisfaction without increasing the risk to other patients. However, there are no guarantees that a patient that tests negative for MRSA will stay negative so retesting would be needed. Keeping patients in contact isolation may be easier and cost effective in limiting the risk of hospital acquired MRSA. Hospitals may not want to invest in the increased cost of ASC and decolonization therapy, but increasing patient satisfaction may be the driving force to reevaluate this issue in light of HCAHPS reimbursement plan. 7. Implications and consequences (all reasoning leads somewhere. It has implications and when acted upon, has consequences). Some research has indicated that contact isolation has not decreased the incidence of hospital acquired MRSA (APIC, 2007). Strict hand hygiene alone has shown to decrease the risk of all nosocomial infections (Henderson, D.K., 2006). By incorporating strict hand hygiene protocol and ASC patients with past history of MRSA may not need to be placed in contact isolation for the rest of their life. ASC could verify current MRSA status before elective surgical procedures. In high risk units such as ICU patients may need to be placed in isolation initially until a negative culture is verified. Routine testing of all patients for MRSA would be costly with minimal benefit. However, in patients with a past history of MRSA the cost may be supported by increased patient satisfaction and decreased need for isolation supplies. Verification of current MRSA status would allow discontinuation of contact isolation protocol without increasing the risk of hospital MRSA acquisition. Routine decolonization of MRSA with Mupirocin has shown variable success rates. Increased antibiotic therapy may enhance the resistance of MRSA to new antibiotics. In cases of elective surgical procedures routine decolonization benefits (decrease risk of post-operative infections and increase patient satisfaction) may outweigh the risks (increasing the resistance, increase cost of ASC and decolonization therapy). 8. Inference and interpretation (all reasoning contains inferences from which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data and situations). Hospital acquired MRSA impacts patient safety and satisfaction. Contact isolation is for the benefit of other people-not the patient that is in isolation. Placing patients with a previous history of MRSA in contact isolation for the rest of their life without verification of current MRSA status has shown to decrease patient satisfaction and may increase the risk of adverse events. Verification of current MRSA status on patients scheduled for elective surgical procedures may eliminate the need for contact isolation. Research has shown that decreasing MRSA in the hospital environment will need to be a multifaceted program that includes strict hand hygiene, staff education, ASC, decolonization therapy, contact isolation protocol, and environmental cleaning protocol. Healthcare beliefs about contact isolation efficacy, hand hygiene, and MRSA colonization all contribute to low compliance rates by healthcare providers in taking care of patients with previous history of MRSA. References Abad, C., Fearday, A., Sadfar, N. (2010). Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov Association for Professionals in Infection Control & Epidemiology, Inc. (APIC). (2007). Guide to the elimination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) transmission in hospital settings. Retrieved from http://www.apic.org Barrat, R., Shaban, R., & Moyle, W. (2010). Behind barriers: patients perceptions of source isolation for methicillin-resistant Stapholococcu aureus (MRSA). Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(2), 53-59. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/prevent/healthcare.html Cummings, K.L., Anderson, D.J., & Kaye, K.S. (2007). Hand hygiene noncompliance and the cost of hospital acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Retrieved from http://www.dynamicrfidsolutions.com/download/article.pdf Dow, G., Field, D., Mancuso, M., & Allard, J. (2010). Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: efficacy and long-term follow-up. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology, 21(1), 38-44. Hardy, K.J., Szczepura, A., Davies, R., & et al. (2007). A study of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of MRSA screening and monitoring on surgical wards using a new, rapid molecular test (EMMS). Doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-160 HCAHPS: Patients’ perspectives of care survey hospital quality… (2011). Retrieved from www.cms.gov Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). (2010). Retrieved from http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/HCAHPS Klein, E., Smith, & D.L., Laxminarayan, R. (2007). Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1995-2005. Retrieved from http://www.nc.cdc.gov/eid/article/13/13/070629_article.htm Pope, D.M., Morrison, G.A., & Hansen, T.S. (2009). MRSA reduction: myths and facts. Nursing Management 40(5), 24-28. (Seigel, J.D., Jackson, M., & Chiarello, L.(2006). Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings, 2006. Retrieved from: www.hicpac.org Zastrow, R.L. (2011). Emerging infections: the contact precaution controversy. American Journal of Nursing, 11, 47-53.