Kris Conrad_Viking

advertisement

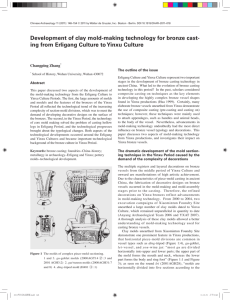

Viking-Age Metallurgy By Kris Conrad ME 401 July 26, 2012 Introduction The history of metal casting has a lot of merit -much like any type of history- in showing us where we’ve come from, and has the potential to greatly influence the further development of future technology. Many methods used in the Roman Iron Age through the Middle Ages (with the Viking Period in between them) are still in some form being used for modern casting. Materials A main alloy used in the Viking era consisted predominately of copper and 30-40% zinc. Although this is often referred to as “Viking Bronze,” strictly speaking, it isn’t actually quite bronze. As Anders Söderberg notes in his article, “In archaeology we often carelessly speak of all copper alloys as "bronze", but it's merely classic bronze, with 90 % copper (Cu) and 10 % tin (Sn) and close related alloys that can claim this name.” What the archaeologists he speaks of refer to as bronze is more accurately a form of brass. This alloy has some advantages over traditional bronze. It is generally less viscous and also has a slower solidification rate. This makes it much easier to pour into molds and allows for more detailed results. The above established brass was very popular in the Roman Iron Age, but was evolved throughout the Viking Period and beyond. Smelters began adding tin (gunmetal), lead (leaded brass), or both (leaded gunmetal) to the mix. Consistently adding lead for desired material properties would likely boil away much of the zinc, making the alloy harder to cast (hence adding lead to lower the melting point) (Söderberg). Some other castable metals worth noting are gold, silver, and pewter. “If gold was the material of high kings, silver for the wealthy, and bronze for the 'middle class' - it remained for pewter to fill the need for the simplest of ornaments (Markewitz).” Pewter is a lead-tin alloy and is highly susceptible to oxidation, meaning it’s not known for its high quality. However, the melting point of pewter is around 750ºF which can easily be obtained on a simple fire. It also pours easily on open-top molds, making it ideal for the lower class citizens. Molding/Casting Methods The average Viking Age casting was done in a clay-walled hearth (a hearth is basically an open furnace) fueled by charcoal. To increase the temperature, they would push air into the hearth through bellows, which would commonly be made of a hide bag attached to a metal, wood, or bone nozzle (“Metalworking and the Smith”). With this setup, the fire was capable of reaching 1100-1200ºC. This is enough to melt bronze for use. However, pure zinc couldn’t be completely melted down. Instead, they heated copper along with zinc ore until the zinc dissolved into the copper in a process known as cementation. Viking Bronze was cast in molds made up of sand-tempered clay mixed with manure which has fibers that are great for the structure of the molds. The clay material was either pressed into shape using a metal pattern on two pieces that were then fit together, or a fairly standard lost wax method (known as “á cire perdue”) was used. There’s some debate over which was more commonly used by the Vikings (Söderberg). In either case, multiple identical molds could be produced. With the press method, the pattern could simply be pressed into multiple molds, and with the lost wax method, one wax pattern could be used to press a mold for many more wax patterns to be poured in. To pour the melted bronze, Vikings used clay crucibles that were sand-tempered to resist both heat and fluxing compounds in the charcoal that would negatively affect the crucible lifespan. Despite the tempering, crucibles rarely lasted more than one or two pours (Söderberg). During the bronze pouring process, metal was melted in one hearth and the molds were fired in another. Since the molds only needed to get up to about 700ºC, bellows were only needed on the melting hearth. Extreme care was taken to make sure the molds were burnt out completely. If the clay wasn’t burnt enough, it would produce gases that could obstruct the metal during the pour. Like any casting, a great deal of skill and coordination was required during the pouring of Viking Bronze. Amazingly, a highly skilled metal caster of this era was sometimes able to produce shelled broaches that were less than a millimeter thick. Relation to Modern Day Metal Casting The methods used by ancient Vikings are quite inspiring. Through the lack of technology, they still managed to efficiently produce some very impressive tools. Through the accumulation of small revelations, metal casting has evolved throughout the ages to what it currently is. Modern day man has discovered many amazing alloys that were never dreamed of 1000 years ago. Even still, metals like brass and bronze are still being casted every day, and it’s still not absolutely perfected. Through small alterations and additions to current material properties, we have the potential to continue the trend of technological progression. If there’s one thing to take away from our history, it’s that improvements can and should always be made. Determination, along with creativity, is the key to innovation. Bibliography Markewitz, Darrell. "Pewter Casting in Stone Moulds." PEWTER CASTING in Soapstone Molds. N.p., 2000. Web. 25 July 2012. <http://www.warehamforge.ca/pewter.html>. "Metalworking and the Smith." Ironworking and the Blacksmith. N.p., 14 Aug. 2004. Web. 25 July 2012. <http://www.viking.no/e/england/york/metal_working_and_the_smith.html>. Söderberg, Anders. "Viking Metal Casting." Viking Metal Casting. N.p., 30 Apr. 1991. Web. 25 July 2012. <http://web.comhem.se/vikingbronze/casting.htm>.