The Muses of Zion

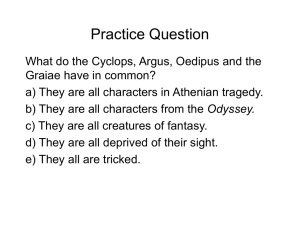

advertisement

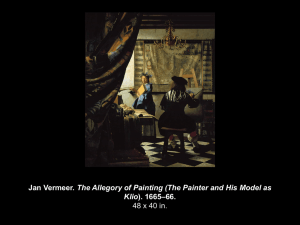

THE MUSES OF ZION “’Tuning the Soul’: Reflections on Music and the Journey to God.” Beginning the series tracing the traditions of Platonic reflection on music and conversion. St George’s Round Church, Lent 2, March 1, 2015 at Evensong. The moment I read Fr Snook’s invitation to speak to you about Platonic reflection on music and conversion, Raphael’s Mount Parnassus with Apollo surrounded by the Muses burst upon my imagination. It is primarily about it, in the context of the other parts of his masterpiece, the Papal Stanza della Segnatura, on which I wish to reflect with you this evening. Since its completion, the Stanza has been recognised as an inspired Christian Platonist exposition of the relation of theology, philosophy, art, and law, matching, and to some degree in dialogue with, Michelangelo’s contemporary work in the Sistine Chapel. However, before setting out on the delights of contemplating it, I must bring and leave before you the first and less happy reflection which this topic elicited. Musike, what the Muses inspire, is the first form of paideia, education and conversion, which Plato treats in the Republic. He asks which rhythms, tones, dances, and stories will appropriately begin the formation of our children’s souls? And which tell the truth about God who is perfect goodness and can only do good. Probably few will dispute his rejection of the ancient versions of acid rock, with priapic oriented skin tight sweaty leather, or of its syrupy sentimental counterparts, meeting Jesus in the garden alone. However, when it comes to the stories Plato would reject, problems remain. It is still a question for us when and how to tell our children that the angel of God slew all the first born of Egypt, both man and beast, that the chosen people sang and danced to celebrate the drowning of Pharaoh and his host, and that God commanded the killing of every living thing in the conquered lands of Canaan. This is only a beginning of the list of Christian stories or myths about God and the saints on which a Platonic reflection on music and conversion forces hard questions for those raising children in the church, probably the hardest concerns the central: Christ’s tortured death as an atoning sacrifice to God for sin. Just as I shall leave behind these hard questions about early education which Platonic philosophical theology requires you to answer, I shall say almost nothing about the fourth wall of the Stanza and its corresponding tondo depicting Justice in the vault above. This fourth fresco depicts the cardinal virtues: Fortitude, Wisdom and Temperance as the means of embodying Justice, below it an Emperor and a Pope authorize law codes. All this is essential to civilized human life, and its lessons must urgently be learned again by a society in which law serves the economy and the very opposite of wisdom and temperance. However, Raphael does not represent justice as inspired, so it is not of the same kind as the other three, and is not part of their interaction. 2 The three great frescoes are of Mount Parnassus, the School of Athens and the Disputation Concerning the Sacrament. Mount Parnassus is presided over by the god Apollo with eyes turned upward for inspiration from divinity above him and is matched by a vault tondo of Poetry with the words of Virgil: “Numine afflatur”, “Inspired by the Spirit”. It is highly significant, and known in Raphael’s archeologically excited age, that, were the window it surrounds to be opened, it would reveal Mount Vatican anciently topped by a temple of Apollo. The School of Athens depicts Plato (who points above) and Aristotle (with hand stretched toward what is below) walking forward from heaven filled vaults. They foster philosophy and the sciences. Above them in the niches to right and left are Apollo with his lyre and helmeted Athena, with her spear and gorgon faced shield, both are gods of knowledge and the arts, invincible Minerva’s include the arts of war. The corresponding ceiling tondo shows us Philosophia, with the motto “Causarum cognitio”, “Knowledge of the causes”, she holds books entitled: “Morals” and “Nature.” For Plato and Aristotle reconciled the first cause is God. The ceiling tondo of the third inspired activity shows Theologia: “Divinarum Rerum Notitia”, “Knowledge of Divine Things”. The Disputation is dominated and centred round the descending Trinity: Father, Son and Spirit made fragilely present in the host stamped with the crucified Jesus signified by IHS. Understanding the sacramental embodiment of God’s Grace, the aim of theology’s endless discussion, requires the assistance of the Philosophia of the School of Athens and of the Musike of Mount Parnassus. Raphael makes this point by placing pagan philosophers with the church doctors among the disputants on the earthly level, by the presence of St Thomas Aquinas, by the repetition of the figure of Dante who appears both here and on Parnassus, and by the two figures at the bottom right of the Mountain who point to the School of Athens. The Muses who share Apollo’s patronage with Philosophy are credited with inventing geometry and astronomy. All this brings me to my first point. The inspired scenes are at the same level; they are not hierarchically ordered. Philosophy & Science, Music & Poetry, Revealed and Philosophical Theology are different, but they are all forms under which God is revealed. As a Christian, Raphael thinks the Trinity to be the most explicit self-revelation of God, and the Eucharist to be the paradigmatic instance of his incarnate presence, but I cannot over emphasize that God, His cosmic order, and His saving uplifting activity among us are present, revealed, and working in all three. These three forms of inspiration are independent and interdependent, because each is from God. Raphael does not believe in the divinity of Apollo, Minerva, and the Muses, but he does demand that we accept a three-fold divine inspiration. Musike has its own proper dignity in the Christian Platonist Summa; this is what Raphael teaches us fundamentally and most importantly. As we move, at long last, beyond the reactionary forms of the 19th century religious revivals, and the Spirit pushes us unwilling out of the fantasy worlds of 3 the Neo-Gothic and Anglo-Catholicism, such visions as Raphael’s are important guides. Deadly for Christianity and the church has been the union of a narrowed aesthetic with aestheticism. Less and less of the artistic imagination and culture is welcomed into the realms of religious preciousness. Yet, simultaneously, what supposes itself to be good taste has substituted itself for the moral, ascetic, evangelical, sacramental, and intellectual essence of religion. Although Parnassus shares with its two neighbours that its figures are from every period, including the contemporary, it is unique in the presence of ladies, including beyond the Muses, the poetess Sappho, labeled so we cannot mistake her, and in the dominance of living nature including a crystal clear stream running down to us. The Mountain of Apollo with his Muses and laurels, providing shade and crowns, is a place of refreshment and peace. It is also a place of conversion. Its most visually demanding gathering of poets, headed by Homer blindly feeling his way towards us, features two of them: Dante to Homer’s right was converted from Hell to Paradise by Virgil on Homer’s left. During that journey, as he tells it in the Comedia, Dante comes upon the poet Statius, here on Virgil’s left. Statius reverences the great Roman guide, “Numine afflatur”, because his prophetic poetry led him to embrace Christianity. Such is the divine power of poetic Musike. Of equal importance with their refreshment, peacemaking, and power to convert is the number and variety of the Muses. They originate and foster: the writing of history, comedy, and tragedy, epic and love poetry, hymns to the gods and rhetoric, dance, geometry and astronomy. The Muses also invent musical instruments: traditionally, the lute, harp, lyre, and guitar. There is no medieval organ but Raphael paints Apollo with a new instrument, the viol. All these poetic and musical arts belong to the Christian life as Raphael painted it and some are essential to the church, what is a hymn except a sung poem? How will we be persuaded and converted without the imagination? And, if music does not stir the emotions and lead them rightly? This miraculously saved building, almost uniquely in these parts able to be liberated from the Neo-Gothic return to chancels filled with pseudo monks, offers opportunities to welcome back to church muses, instruments, and music too long expelled. Apollo’s viol may look frightening like a guitar played with a bow; do not fear that I am urging you to replace the organ with a guitar. But even its unwelcome ubiquity urges us backwards and outwards to a fuller acceptance of the Muses and those who bring their arts. Many of them, their painters, carvers, players and singers, and the people who identified with them were expelled when Neo-Gothic aesthetically correct refinement came up the aisle. Let us invoke the Renaissance spirit and draw in all who can join us in singing the songs of Zion, building her temples, and performing her arts. Wayne J. Hankey February 26, 2015.