Great Wall - NCTA-Vietnam-China-2011

advertisement

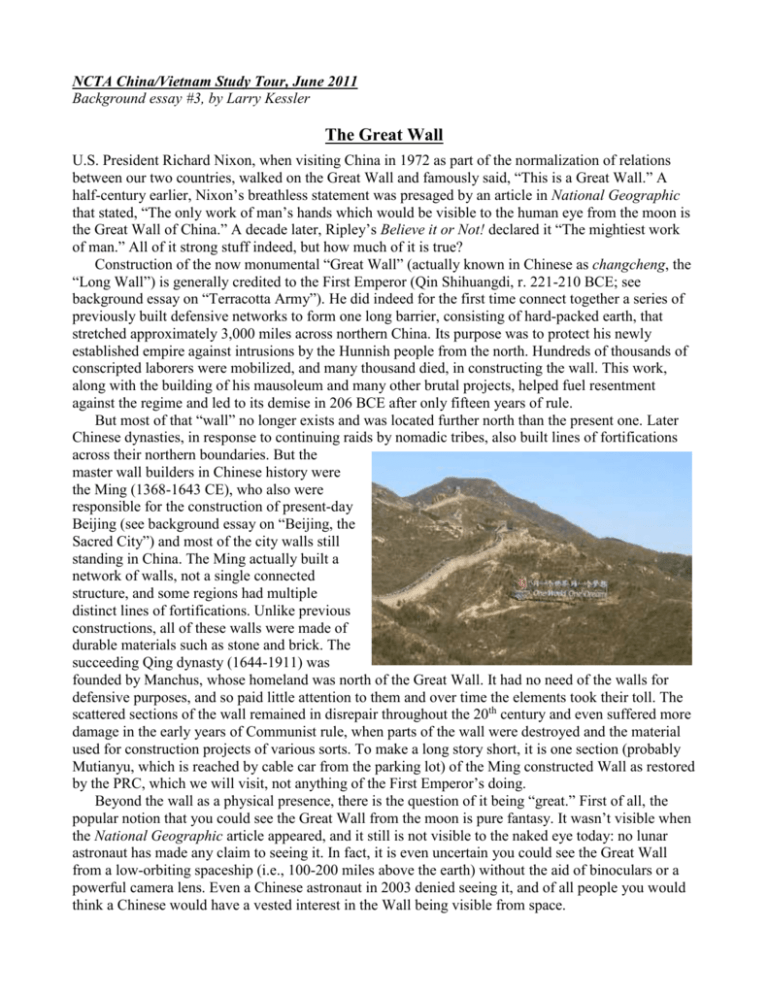

NCTA China/Vietnam Study Tour, June 2011 Background essay #3, by Larry Kessler The Great Wall U.S. President Richard Nixon, when visiting China in 1972 as part of the normalization of relations between our two countries, walked on the Great Wall and famously said, “This is a Great Wall.” A half-century earlier, Nixon’s breathless statement was presaged by an article in National Geographic that stated, “The only work of man’s hands which would be visible to the human eye from the moon is the Great Wall of China.” A decade later, Ripley’s Believe it or Not! declared it “The mightiest work of man.” All of it strong stuff indeed, but how much of it is true? Construction of the now monumental “Great Wall” (actually known in Chinese as changcheng, the “Long Wall”) is generally credited to the First Emperor (Qin Shihuangdi, r. 221-210 BCE; see background essay on “Terracotta Army”). He did indeed for the first time connect together a series of previously built defensive networks to form one long barrier, consisting of hard-packed earth, that stretched approximately 3,000 miles across northern China. Its purpose was to protect his newly established empire against intrusions by the Hunnish people from the north. Hundreds of thousands of conscripted laborers were mobilized, and many thousand died, in constructing the wall. This work, along with the building of his mausoleum and many other brutal projects, helped fuel resentment against the regime and led to its demise in 206 BCE after only fifteen years of rule. But most of that “wall” no longer exists and was located further north than the present one. Later Chinese dynasties, in response to continuing raids by nomadic tribes, also built lines of fortifications across their northern boundaries. But the master wall builders in Chinese history were the Ming (1368-1643 CE), who also were responsible for the construction of present-day Beijing (see background essay on “Beijing, the Sacred City”) and most of the city walls still standing in China. The Ming actually built a network of walls, not a single connected structure, and some regions had multiple distinct lines of fortifications. Unlike previous constructions, all of these walls were made of durable materials such as stone and brick. The succeeding Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was founded by Manchus, whose homeland was north of the Great Wall. It had no need of the walls for defensive purposes, and so paid little attention to them and over time the elements took their toll. The scattered sections of the wall remained in disrepair throughout the 20th century and even suffered more damage in the early years of Communist rule, when parts of the wall were destroyed and the material used for construction projects of various sorts. To make a long story short, it is one section (probably Mutianyu, which is reached by cable car from the parking lot) of the Ming constructed Wall as restored by the PRC, which we will visit, not anything of the First Emperor’s doing. Beyond the wall as a physical presence, there is the question of it being “great.” First of all, the popular notion that you could see the Great Wall from the moon is pure fantasy. It wasn’t visible when the National Geographic article appeared, and it still is not visible to the naked eye today: no lunar astronaut has made any claim to seeing it. In fact, it is even uncertain you could see the Great Wall from a low-orbiting spaceship (i.e., 100-200 miles above the earth) without the aid of binoculars or a powerful camera lens. Even a Chinese astronaut in 2003 denied seeing it, and of all people you would think a Chinese would have a vested interest in the Wall being visible from space. The term “Great Wall” itself is of Western origin, a product of 18th and 19th century explorers and missionaries who toured ruins of the Ming walls and assumed they were the remnants of an unbroken 3,000-mile long wall associated with the First Emperor a couple of millennia earlier. One Englishman even extrapolated from one small section near Beijing and calculated that the entire structure must have had enough stone to build two small walls around the equator! By the 20th century, Westerners routinely referred to the structure as the Great Wall. Chinese, on the other hand, were at first indifferent to these claims of greatness. It was Sun Yatsen, who was leading a revolution against the old order and calling for a new sense of nationalism, who first latched on to the Great Wall idea as a way to create a modern Chinese identity. The Wall thus became a national symbol of strength and pride, a monumental work that only the Chinese people could have created. (Sun had grandiose ideas and plans: it was he who also first envisioned damming the Yangzi to control flooding and create hydro-electric power, an idea that found fruition in the gargantuan Three Gorges Dam at the end of the 20th century.) Leftist revolutionaries continued the transformation of the Wall into a heroic symbol. Mao Zedong, while on the Long March (1935-1936), wrote a poem that included these lines, “We shall the Great Wall reach, / or no true soldiers be.” During the War of Resistance against Japan (1937-1945), the song “March of the Volunteers,” which later was adopted as the national anthem of the PRC, called upon all “who would not be slaves / to take our own flesh and blood, / to build a new Great Wall.” But, as mentioned above, once in power the Communists began to destroy things associated with the hated past, including stretches of the Wall, and replaced them with “newly born things,” such as an expanded Tiananmen and the Great Hall of the People. It was only in the 1980s that the current regime began to see the Wall as a potent symbol of China and a great source of tourist revenue. Inspired by Deng Xiaoping’s call in 1984 to “love our country and restore the Great Wall,” the government began campaigns, which are still ongoing, to restore great sections of it. In contemporary China, the Great Wall is a popular name for corporations and products, and a theme in paintings, song, woodcarvings, and other artistic endeavors. One spectacular example is the enormous 16by-32-ft tapestry hanging in the United Nations depicting the Great Wall, a gift from the PRC in 1974 after it replaced Taiwan as China’s representative in that body. A popular Chinese saying today is, paraphrasing Mao’s poem, “you are not a real man until you have climbed the Great Wall,” and I have seen very elderly men and women, helped by their children, crawling on all fours up some of its steep steps. And, as we know from television images, every foreigner on a state visit to China makes an obligatory trip to the Great Wall. President Obama visited in 2009, posed for an iconic photo-op (that was later appropriated for a billboard ad in Times Square) and remarked, “It’s magical. It reminds you of the sweep of history.” But, like us, you don’t have to be a distinguished visitor to feel obliged to see the Great Wall and admire it as a proud symbol of a great country and great people. Still, the old misconceptions remain. Take this example of a tour agency’s lure, “Just like a gigantic dragon, with a history of more than 2000 years the Great Wall winds up and down across deserts, grasslands, mountains and plateaus, stretching approximately 5,500 miles from east to west of China.” And, if you wish, at the end of your visit to the Wall you can obtain a certificate attesting to having been on the “only man-made structure visible from the moon.” Suggested Reading John Man, The Great Wall (Cambridge, Mass: Da Capo Press, 2008) Carlos Rojas, The Great Wall: a Cultural History (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010) Arthur Waldron, The Great Wall of China (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990)