AAD Ad Hoc Task Force on Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine

advertisement

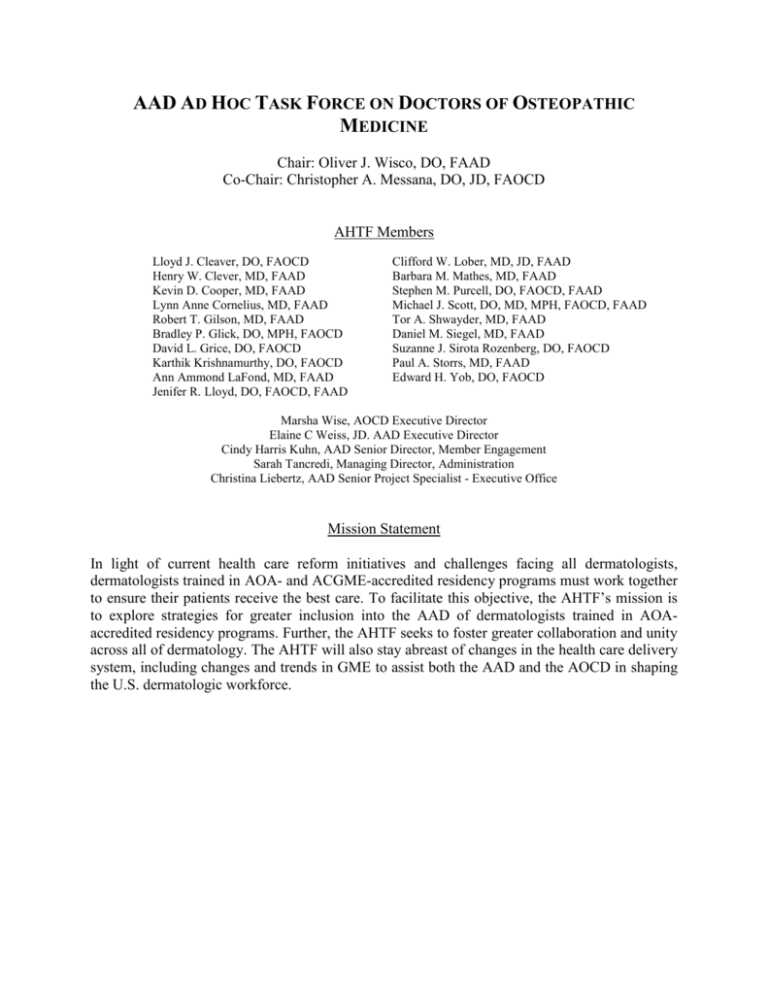

AAD AD HOC TASK FORCE ON DOCTORS OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE Chair: Oliver J. Wisco, DO, FAAD Co-Chair: Christopher A. Messana, DO, JD, FAOCD AHTF Members Lloyd J. Cleaver, DO, FAOCD Henry W. Clever, MD, FAAD Kevin D. Cooper, MD, FAAD Lynn Anne Cornelius, MD, FAAD Robert T. Gilson, MD, FAAD Bradley P. Glick, DO, MPH, FAOCD David L. Grice, DO, FAOCD Karthik Krishnamurthy, DO, FAOCD Ann Ammond LaFond, MD, FAAD Jenifer R. Lloyd, DO, FAOCD, FAAD Clifford W. Lober, MD, JD, FAAD Barbara M. Mathes, MD, FAAD Stephen M. Purcell, DO, FAOCD, FAAD Michael J. Scott, DO, MD, MPH, FAOCD, FAAD Tor A. Shwayder, MD, FAAD Daniel M. Siegel, MD, FAAD Suzanne J. Sirota Rozenberg, DO, FAOCD Paul A. Storrs, MD, FAAD Edward H. Yob, DO, FAOCD Marsha Wise, AOCD Executive Director Elaine C Weiss, JD. AAD Executive Director Cindy Harris Kuhn, AAD Senior Director, Member Engagement Sarah Tancredi, Managing Director, Administration Christina Liebertz, AAD Senior Project Specialist - Executive Office Mission Statement In light of current health care reform initiatives and challenges facing all dermatologists, dermatologists trained in AOA- and ACGME-accredited residency programs must work together to ensure their patients receive the best care. To facilitate this objective, the AHTF’s mission is to explore strategies for greater inclusion into the AAD of dermatologists trained in AOAaccredited residency programs. Further, the AHTF seeks to foster greater collaboration and unity across all of dermatology. The AHTF will also stay abreast of changes in the health care delivery system, including changes and trends in GME to assist both the AAD and the AOCD in shaping the U.S. dermatologic workforce. Position statement and requests In an era when dermatologists’ ability to deliver high quality and cost effective care to our patients is under attack by legislators, regulators, and private payers, the need for dermatologists to advocate with a unified voice on behalf of patients and the profession has never been greater. In the current health care reform environment all dermatologists are facing unprecedented challenges on multiple fronts that pose a growing impediment to their collective ability to provide high quality, cost-effective and efficient care to patients. These challenges include the elimination of providers from insurance networks, which deprives patients of access to appropriate care; increasingly burdensome federal and state regulation affecting virtually all areas of practice; changes to scope of practice regulations that degrade the standard of care; and ever-decreasing reimbursement by public and commercial payers. Now is the time for dermatologists to unite and speak with a clear, single voice to advocate on behalf of all boardcertified dermatologists to ensure that all patients have access to the highest quality, costeffective dermatologic care. Accordingly, the AAD established an ad hoc task force to explore strategies to unify all board certified dermatologists in order to increase participation in advocacy and leadership for patients and the profession. To advance these objectives, the task force respectfully requests that the AAD Board: 1. Allow membership to vote in March 2015 election to approve a modification to the bylaws granting AAD Fellow member status to American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology (AOBD)-certified dermatologists; 2. Implement an educational initiative to help AAD members better understand the education and training of AOBD-certified dermatologists and why they should be fully included in the AAD by granting them Fellows status; 3. Establish AOCD representation within the AAD governance structure with inclusion of AOCD members in positions of leadership to be defined by the AAD Board of Directors. The following sections of this document provide background information on the requests: Section I Section II Section III Section IV Section V Unsuccessful votes to amend AAD bylaws to allow AOBD-certified dermatologists to become Fellows of the AAD Historical biases against accepting DO physicians into ACGME dermatology residency and fellowship programs Comparison of AOA and ACGME dermatology residency training systems Comparison of the organizational structure and oversight of AOA and ACGME dermatology training, certification, and membership representation Proposed plan for educating AAD membership regarding the merger of AOA and ACGME dermatology training to increase understanding of the house of medicine’s direction and to increase voting in favor of the bylaws amendment References: 1. AOA-ACGME Residency Merger Announcement 2. Comparison of AOA and ACGME Program Requirements for Dermatology Graduate Medical Education 3. RFA - DO 2009 4. RFA - DO 2004 Section I: Unsuccessful votes to amend AAD bylaws to allow AOBD-certified dermatologists to become Fellows of the AAD AAD membership has voted twice in recent years (2004 and 2010) to amend the AAD bylaws to allow AOA-accredited, residency-trained/AOBD-certified DO dermatologists to become Fellows of the AAD. On both occasions, a majority of the membership voted in favor of passing the amendment (59% in 2004; 62% in 2010), but the required two-thirds majority to approve a bylaws amendment was not achieved and so the amendment failed. Unlike the AAD, the majority of national medical specialty societies include DOs as Fellows within their membership structure and organizations. Although DOs are not recognized currently as Fellows of the Academy, they are Affiliate members. DOs play a valuable role in many Academy committees and initiatives; however, Affiliate members are prohibited from serving in elected office. There are currently 346 DO Affiliate members of the Academy. Resistance to granting Fellow status to AOA-accredited residency trained DO dermatologists has been primarily based upon misperceptions regarding the standards, requirements, certification, and oversight of AOA-accredited dermatology residency training programs. However, the recent announcement by ACGME, AOA, and AACOM that a single, unified accreditation system for the nation’s graduate medical programs will be adopted by 2020 significantly changes the landscape. This unification should serve to dispel these entrenched misconceptions and act as a catalyst for AAD membership to reconsider a bylaws amendment to grant Fellow status to AOAaccredited residency trained DO dermatologists. Additionally, the challenges facing the profession, including health care reform, make ratification of this issue timely. Section II: Historical bias against accepting DO physicians into ACGME-accredited dermatology residency and fellowship programs Currently, few osteopathic (DO) physicians are training in ACGME dermatology residencies. The 2013 ACGME match results revealed 115 ACGME dermatology residency programs with a total of 407 positions (combined PGY-1 and PGY-2). Of those 407 positions, 387 were filled by US MDs, four by US International Medical Graduates (IMG), four by non-US IMGs, four by DOs, and eight went unfilled. In light of the fact that significant numbers of DO applicants apply for ACGME dermatology residencies, these numbers imply the existence of a bias against the selection of DOs to these positions. Due to the historical paucity of DOs that have been accepted to ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs, DO applicants apply mostly to osteopathic dermatology residencies. ACGME program directors have stated that they are uncertain as to how to compare COMLEX scores and USMLE scores and have questions as to the equivalence of medical education in osteopathic and allopathic medical schools. These factors may serve as two principle sources of bias against acceptance of DOs to ACGME residency and fellowship programs. COMLEX and USMLE exams COMLEX exam scores are used in the licensing process for DOs and are required for licensure by the medical licensing boards of all 50 states. COMLEX is a series of examinations that are created and administered by the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners (NBOME). The Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States has comprehensively reviewed COMLEX-USA and USMLE and concluded that both are valid and reliable measures of the competence of DOs and MDs, respectively. With such a wealth of outstanding applicants in the dermatology pool, USMLE scores are typically an initial filter in screening applicants for further consideration or interview. ACGMEaccredited dermatology residency programs commonly select a minimum USMLE score below which applicants are excluded from further consideration. DO applicants who have taken only the COMLEX exams may find themselves screened out. This requires DO applicants to take both examinations, which imposes additional burdens that MD students do not face. Unfortunately, there is no standard scale to convert COMLEX to USMLE scores and to date there have been no successful conversion tools to aid GME directors in this comparison. One conversion tool, published from the Kirksville (MO) College of Osteopathic Medicine, was based on 155 osteopathic students at that institution who took both USMLE step 1 and COMLEX level 1 and 56 students who took both level 2 exams. It’s uncertain whether these findings could be generalized to students from other osteopathic medical schools. Also there are limitations to the simple conversion formula due to variations in both USMLE median scores and standard deviations from year to year. It appears that GME directors that have taken the USMLE themselves (i.e., MDs) are likely to rely on it rather than try to translate COMLEX score reports. Though some residencies accept either USMLE or COMLEX scores, many residencies appear to not view them as interchangeable in their selection process. With the future integration of accreditation systems, it’s likely that both exams will become accepted as equivalents. Just as undergraduate universities are generally comfortable interpreting both SAT and ACT scores in evaluating applicants, one can envision GME programs in the imminent, unified accreditation system being comfortable interpreting both USMLE and COMLEX exam scores. For ACGME program directors, a reasonable option in equating the tests may be to use the national percentile ranking of a given COMLEX score. Using the national percentile ranking rather than the raw score may simplify evaluation of applicants, as the subject matter tested in the two series of exams is substantially the same. The COMLEX level one exam covers the basic medical sciences, including anatomy, behavior science, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, pharmacology, and physiology as well as osteopathic principles and practice. The COMLEX level 2 exam is taken in the 3rd or 4th year of osteopathic medical school and evaluates knowledge of clinical medicine, including emergency, family and internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, general surgery, and osteopathic principles and practice. There is substantial similarity between the preclinical and clinical undergraduate medical education of DOs and MDs and between the COMLEX and USMLE exams. Osteopathic (DO) vs allopathic (MD) undergraduate medical education ACGME program directors may also be biased against DO applicants due to their lack of familiarity with the similarities of training within allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. Some may not regard osteopathic graduates equivalent when making resident selections. While both degrees are recognized for the practice of medicine, there are some differences in the training styles. While osteopathic medical education allows for the ability to train in any specialty, it philosophically emphasizes holistic care or a patient-centered approach that often leads DO students on a path towards primary care. In addition, the clinical rotations of the 3rd and 4th years of osteopathic medical school have historically been conducted in communitybased hospitals. In recent decades, however, they regularly occur on regional medical campuses and in large traditional academic medical centers and universities. All DO clinical training sites must now undergo strict evaluation for approval by the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditations (COCA). Osteopathic medical schools require an additional course in osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM), which is incorporated continuously into the four-year medical school curriculum. OMM training integrates a patient-centered philosophy with a hands-on approach to diagnosing and treating the patient. There are currently 141 US medical schools that award the MD degree and 29 colleges of osteopathic medicine that grant the DO degree. Currently more than one in five medical school students enter osteopathic medical schools. In 2011-12, 5,788 students matriculated into osteopathic medical schools and 19,517 matriculated into allopathic medical schools. While some have pointed to a slight difference between the average MCAT score and GPA for students entering osteopathic and allopathic medical schools, this gap has narrowed in recent years. USMLE pass rates for DO and MD students respectively in 2012: Step 1: 91% and 94%, Step 2 CK: 96% and 97% Step 2 CS: 87% and 97% Step 3: 100% and 95% Graduates of both DO and MD medical schools are eligible to Note: very few DO students (under 50) take the Step 2 CS exam or the Step 3 exam. Step 2 CS takers: 17,118 MDs vs 46 DOs Step 3 takers: 19,056 MDs vs. 16 DOs apply to residency programs through the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), which represents ACGME-accredited residency programs. The 2014 match results show that 94.4% of graduating MDs matched to an ACGME residency. More than 60 percent of DO graduates currently are training in ACGME programs. This is the first year that the osteopathic dermatology residency programs have participated in the AOA match. There are currently 27 AOA-accredited dermatology residency programs with 119 total residency positions available. In the past, MDs have not been permitted to train in AOA-accredited residencies, though this has recently become a possibility with a new agreement between the AOA and ACGME. In terms of licensure, the main difference is that the USMLE is required for MDs and the COMLEX is required for DOs. The requirements for maintaining a physician license for MD and DOs are nearly identical in most states and both degrees are recognized internationally as medical degrees. One university-based dermatology department has had 12 years of successfully incorporating osteopathic residents into their residency program and has provided an opportunity for reasonably comparing the achievement of DO and MD dermatology residents. University Hospitals Case Medical Center of Cleveland began accepting osteopathic residents in 2002. This program is totally integrated and dually accredited by both the ACGME and AOA. The American Board of Dermatology In-Training Exam (ABD ITE) is a department requirement and 12 years of scores are summarized below. AVERAGE TOTAL % CORRECT SCORES: 2002-2014 PGY 2 3 4 DO 57.91 69.43 76.22 MD 66.64 70.90 73.89 2 DOs per year / 4-6 MDs per year This data demonstrates that DO and MD residents have performed at a very similar level based upon their nearly equivalent scores on the ABD ITE. In addition, DO residents in the UHCMC program have been selected by the faculty to serve as academic chief resident, have won NIH awards, and have been described by faculty as a “true asset to the UHCMC program.” Section III: Comparison of AOA and ACGME dermatology residency training systems A comparison of the AOA and ACGME standards for residency training in dermatology was conducted by the AOCD. AOA Basic Documents for Postdoctoral Training and the AOA/AOCD Basic Standards for Residency Training in Dermatology were reviewed for AOA-accredited residency programs. The ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology were reviewed for ACGME-accredited residency programs. The AOCD found that the vast majority of the osteopathic and allopathic standards were comparable, if not uniform. In areas where standards differed, training requirements were not significantly affected. The following highlights the pertinent findings: The introduction and mission statement of both documents establish the same goals for residency training in dermatology: To prepare residents, in a progressive manner, to become an independent, competent, and professional dermatologists over the course of an educational program that is 36 months (3 years) in length. Sponsoring institutions are required to provide program directors with adequate support and resources to meet program standards and assume responsibility for the program. Both sets of standards require written affiliation agreements between the program and any affiliated sites, which establish parameters and responsibilities of trainees and faculty for each rotation. Programs are required to have a qualified program director in place. Both sets of standards require the program director to be certified in dermatology (AOA requires AOBD or ABD certification; ACGME requires ABD certification). The ACGME requires changes in program directors to be reported through the Accreditation Data System (ADS), while the AOA requires these to be submitted to the AOA Division of Postdoctoral Training. Program directors must hold appropriate medical licensure and staff privileges. In addition, they must have full-time dermatology practice experience following residency or fellowship. The AOA requires five years of experience, and the ACGME requires four. At least three years of faculty experience in an accredited dermatology residency is required (the AOA standards require this to be in an AOAor ACGME-accredited program; the ACGME standards require this to be gained only in an ACGME-accredited program). The osteopathic standards require the program director to be a member in good standing of the AOCD. Program directors are responsible for overseeing the development of the curriculum and training while monitoring effectiveness of the program, faculty, and rotations to ensure competency objectives are met and trainees are adequately supervised. Program directors are responsible for evaluating trainee performance and supervision, as well as providing trainees with policies and procedures pertaining to program requirements and expectations. Resident duty hours must be monitored with backup support provided and schedules adjusted as needed to mitigate fatigue while maintaining continuity of patient care. Both sets of standards require the program director to comply with the policies and procedures of the sponsoring institution and the accrediting organization. Program directors are responsible for providing verification of residency education for all residents, including residents who leave the program before completion of training. The ACGME standards require that an interim program director be appointed during the temporary absence of the program director, which should not exceed six months. The AOA standards do not contain provisions for an interim program director. Both sets of standards require a sufficient number of qualified faculty to be actively involved in the education, training, and supervision of residents. Faculty must demonstrate a dedication to resident education and possess appropriate medical licensure, credentials, and staff privileges along with certification in any specialty or subspecialty areas in which they are teaching. The AOA requires trainers to be certified by either the AOBD or ABD; the ACGME requires ABD certification or qualifications deemed acceptable by the Review Committee. AOA standards require a ratio of one board certified osteopathic dermatologists for every two residents; the ACGME standards require a faculty-to-resident ratio of one to three. The ACGME standards stipulate that the presence of other learners must not interfere with the residents’ education and require the program director to report the presence of other learners to the DIO and GMEC. The AOA standards do not contain these requirements. Both sets of standards call for adequate resources, including equipment, support staff, didactic conference space, and medical reference material to be provided by the base institution to support the number of residents and maintain the quality of education. Residents must successfully complete an internship year prior to starting a residency in dermatology. The osteopathic standards require an AOA-approved traditional internship or appropriate OGME-1 training program. The allopathic standards require a broad-based clinical year in an ACGME-accredited program. Programs are required by both sets of standards to provide training and resident patient care responsibility on a progressive, graduated basis with competency-based objectives. Residents must be supplied with program requirements and expectations. Residency programs are required to provide regularly scheduled didactics and lectures on topics pertinent to training and study in dermatology. The ACGME standards require cosmetic techniques and the interpretation of direct immunofluorescence specimens to be included in didactics; this is not explicitly required by AOA standards. The osteopathic standards require that the Osteopathic Core Competencies be integrated into all programs, and allopathic standards require the ACGME standards be integrated. These competencies are patient care and procedural skills, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Residents are required to provide compassionate, appropriate, and effective patient care while incorporating preventative medicine and health promotion. Residents must be instructed to perform dermatological diagnostic and surgical techniques and other modalities across all age groups. They must demonstrate knowledge of accepted standards of clinical medicine in dermatology and remain current with new developments through a commitment to lifelong learning. Residents must be able to apply this knowledge to patient care across all age groups. Residents are required demonstrate the ability to evaluate their care of patients, integrate evidence-based medical principles into patient care, show an understanding of research methods, and improve patient care. Residents must demonstrate interpersonal and communication skills that enable them to establish and maintain professional relationships with patients, families, and other members of health care teams. Residents must promote advocacy of patient welfare, adherence to ethical principles, collaborate with health professionals, lifelong learning, and sensitivity to a diverse patient population. Residents are required possess an understanding of health care delivery systems and provide qualitative patient care while practicing cost-effective medicine within the system. Residents must maintain detailed log documenting all supervised surgical procedures performed during residency. The ACGME standards require this information to be entered into the ACGME Case Log System. Allopathic and Osteopathic residency programs must provide didactic lectures, consultation and inpatient experience, subspecialty experience, and clinical conferences. Residents should participate in scholarly pursuits, with resources and support being provided by the sponsoring institution. Programs must budget time and funding to allow residents to attend a national meeting. ACGME standards require residents to follow a core group of patients throughout the majority of the program in a once-monthly continuity of care clinic. This is not required by the AOA; however, in-patient dermatology experience is required. Both sets of standards establish education committees to regularly review resident evaluations and verify that educational objectives and competencies are being met. Programs must document resident performance improvement as the resident progresses in the program. Program directors are required to review resident performance at least semiannually. Evaluations must be accessible for review by the resident. Program directors must provide a cumulative evaluation for each resident upon completion of the program and provide verification of successful completion of the program. A system must be in place to facilitate evaluation of the core faculty by the program. The ACGME standards contain specifics that are not explicitly required by the AOA standards. The ACGME requires faculty evaluations to be conducted at least annually, which must include a review of clinical knowledge and teaching abilities, commitment to the educational program, scholarly activities, and professionalism. Evaluations must contain written confidential evaluations provided by the residents. A system must be established that assesses and measures the effectiveness of the program and establishes opportunities for improvement. Programs must commit to promoting patient safety with resident participation in clinical quality improvement and patient safety programs. Both AOA and ACGME standards require programs to commit to a balance between education and service. The osteopathic standards call for 75 percent of the training experience to involve direct patient care. The educational experience should not be compromised by reliance on residents to perform institutional service obligations. A culture of professionalism must be maintained that supports patient safety and personal responsibility. Residents must understand and accept their role in patient safety and welfare, patient/family-centered health care, assurance of fitness for duty, time management before, during and after duty, recognition of impairment, and attention to lifelong learning. Processes must be in place to minimize the number of transitions in patient care and help ensure patient safety and continuity of patient care. Faculty must be able to recognize fatigue and sleep deprivation and adjust schedules as necessary. Adequate facilities must be provided to any resident too fatigued to safely travel home. Both sets of standards call for residents to be supervised and provided with reliable access to supervision throughout the program. Supervision is to be provided on a graduated basis as the resident makes progress in the program. Supervising physicians are responsible for determining which activities the resident is allowed to perform. Senior residents should have a role in the supervision of junior residents. Residents are responsible for seeking consultation when required. The AOA and ACGME standards both require duty hours to be limited to 80 hours per week, averaged over a four-week period, inclusive of all in-house call activities and moonlighting. Moonlighting must not interfere with the resident’s performance and ability to successfully meet the goals and objectives of the program. The AOA requires the approval and permission of the program administration before moonlighting is allowed. Interns (OGME-1/PGY-1) are prohibited from moonlighting. Programs should avoid scheduling excessive work hours, which may lead to sleep deprivation and fatigue. Residents shall not work in excess of 24 consecutive hours. Allowances may be made to allow for effective transfer of care; however, this period of time must not surpass four hours. Residents shall not assume responsibility for a new patient or additional clinical responsibilities after working 24 hours. In cases where a trainee is engaged in patient responsibility that cannot be interrupted at the duty hour limits, additional coverage should be assigned as soon as possible to relieve the trainee. Patient care responsibility is not precluded by the duty-hours policy. Documentation must be submitted to the program director/DME providing rationale for remaining to provide care. Section IV: Comparison of the organizational structure and oversight of AOA and ACGME dermatology training, certification, and membership representation The American Osteopathic Association (AOA), its component bureaus, councils and committees, and affiliated organizations, including but not limited to the Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions (OPTI), the Bureau of Osteopathic Specialties (BOS), the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology (AOCD) and the American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology (AOBD) collectively operate to serve all of the same functions as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), the American Medical Association (AMA), the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Board of Dermatology (ABD), the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). The principle difference between the AOA and ACGME systems is that osteopathic medical education and residency training are subject to the authority and oversight of the AOA while the allopathic undergraduate medical education system and the ACGME system are overseen by multiple independent organizations. We will specifically discuss and clarify the respective roles of the entities involved in: (1) accreditation of colleges of osteopathic medicine; (2) accreditation of osteopathic dermatology residency programs; (3) administration and oversight of the policies, practices, and standards governing osteopathic dermatology residency programs and their trainees; (4) board certification (including certifications of added qualification for dermatopathology and Mohs micrographic surgery, respectively) and recertification for osteopathic dermatology; (5) accreditation of activities of continuing medical education for osteopathic dermatologists; and (6) professional advocacy to all stakeholders on behalf of osteopathic physicians, fellows, residents and medical students. American Osteopathic Association The American Osteopathic Association (AOA) is a private, nonprofit organization founded in 1897 to advance the osteopathic medical profession by uniting the efforts of individual osteopathic physicians (DOs) and colleges. The AOA is a member association representing more than 82,000 DOs and 20,000 osteopathic medical students. Additionally, the AOA, through its various bureaus, councils, committees, and affiliate organizations serves as the primary certifying body for DOs; accredits and oversees all osteopathic postdoctoral training programs and medical colleges; and has federal authority to accredit hospitals and other health care facilities. All osteopathic postdoctoral training programs are authorized throughout the United States in federal and state laws, rules, and regulations. Presently there are approximately 87,300 osteopathic physicians and 29 colleges of osteopathic medicine graduating more than 5,100 new osteopathic physicians annually. In the last fifty years the number of osteopathic physicians has grown by 515 percent. Osteopathic physicians are in practice in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C. Pursuant to the agreement between the AOA and ACGME to establish a single GME accreditation system between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2020, AOA-approved training programs that are AOA-accredited can register for ACGME pre-accreditation status and begin applying for ACGME accreditation. AOA-accredited programs are expected to complete the transition to ACGME accreditation before July 1, 2020. The AOA will cease providing GME accreditation in July, 2020. The AOA is led by its Board of Trustees (BOT). The AOA BOT is the administrative body of the AOA with authority to conduct all business of the AOA when the AOA House of Delegates is not in session and when such policies are essential to the management of the AOA. Such duties include the management of the AOA’s finances; appointments to bureaus, councils, and committees; decisions on all questions of ethical and judicial issues; and review and approval of amendments to the constitution, bylaws, and regulations of affiliated organizations. The AOA also helps shape health policy at the federal level. The AOA nominates individuals to serve on panels for a number of these agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The AOA has numerous policy committees that monitor and comment on a wide array of initiatives, including the profession’s contact with the United States Congress and the various US government departments, bureaus, and agencies advising on scientific aspects of health care, including osteopathic medicine and biomedical research. Such activities routinely involve reviewing AOA policy guidelines relative to health care, health planning, and health delivery. For comparison, the LCME, which is jointly sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (whose osteopathic counterpart is the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine) and the Council on Medical Education of the AMA, accredits medical education programs in the United States and Canada culminating in the award of the MD degree. The AMA is the largest membership association of physicians in the US, representing both MDs and DOs. The AMA’s stated mission is to promote the art and science of medicine for the betterment of the public health, to advance the interests of physicians and their patients, to promote public health, to lobby for legislation favorable to physicians and patients, and to raise money for medical education. In contrast to the AOA, the AMA has no role in certifying or recertifying dermatologists. AOA Council on Postdoctoral Training The AOA Council on Postdoctoral Training (COPT) is a representative body composed of members from AOA Affiliate organizations and was created to ensure that postdoctoral training programs operate in compliance with approved standards, rules and regulations, and provide educational training consistent with the public interest. The COPT was created by the AOA BOT in 2003 and has the obligation to deliberate upon and recommend policy revisions to the Bureau of Osteopathic Education (BOE) and the AOA BOT for improvements in postdoctoral education. The AOA COPT reviews policy and basic requirements regarding OGME (osteopathic graduate medical education), including internship and residency programs. The COPT receives and reviews reports from its subordinated PTRC and its subordinated Council on Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions (COPTI). The COPT receives reports from the education evaluating committees (EEC) of the specialty practice affiliates, such as the AOCD regarding standards development, outcomes, and on-site evaluation of training programs. The COPT communicates its findings back to the EECs, including any recommendations for improvement. The COPT also makes recommendations to the BOE. Ultimately, the AOA BOT acts on recommendations from the BOE and makes final decisions. All COPTIs are overseen by the AOA COPT, which is the review committee under the authority of the PTRC that oversees the OPTI accreditation process and has the responsibility for assuring ongoing compliance with accreditation standards. COPTI makes recommendations to the PTRC, which is a council subordinate to the AOA BOE. The ACGME is somewhat analogous to the AOA COPT. However, while the ACGME is an independent organization with ultimate authority over the graduate medical education programs it accredits, the COPT operates pursuant to the authority of the AOA BOT. Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions Recognizing the need for a new system to structure and accredit osteopathic graduate medical education, the AOA established the Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions (OPTI) in 1995. Each OPTI operates under the authority of the COPT and is a community-based training consortium comprised of at least one college of osteopathic medicine and one hospital. Other hospitals and ambulatory care facilities may also partner within an OPTI. Certain communitybased health care facilities such as ambulatory care clinics, rehabilitation centers, and surgical centers may now have the resources and support necessary to provide physician training with an OPTI's assistance. AOA-approved internships and residencies are regularly reviewed by their respective OPTIs. There are currently 20 OPTIs. An OPTI is the functional equivalent of a traditional university hospital that has multiple medical clinics of various specialties and facilitates the clinical clerkships of medical students and ACGME-accredited graduate medical education of residents and fellows. Training sites may be in-house or at affiliated locations. Part of the OPTI accreditation process includes encouraging clinical medical education research. Research programs are available to osteopathic interns and residents throughout each year of training. These research programs are developed in conjunction with guidelines and requirements of osteopathic specialty colleges for residency training programs and the COPT for internship programs. AOA Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists The AOA BOS is the certifying body for the approved specialty Boards of the AOA, including dermatology, and is dedicated to establishing and maintaining high standards for certification of osteopathic physicians. The BOS ensures that the osteopathic physicians it certifies demonstrate expertise and competence in their respective areas of specialization. The BOS is committed to the delivery of quality health care to all patients by working with all of its approved specialty certifying boards through the continuous improvement of its certification process. There are currently 18 certifying boards within the BOS, not including certifications of special qualification and certifications of added qualification. The ABD is one of 24 medical specialty boards that make up the ABMS, a not-for-profit organization overseeing the certification of physician specialists in the United States. Although the ABD and the ABMS are analogous to the AOBD and the BOS, the AOBD and BOS operate pursuant to the authority and oversight of the AOA, while the ABD and ABMS are each independent organizations. American Osteopathic College of Dermatology The AOCD is a specialty society recognized by the AOA and was founded in 1957. The mission of the AOCD is to improve the standards of the practice of dermatology by promoting both the expansion and dissemination of knowledge of the specialty of dermatology and the awareness of the scope of services provided by DO dermatologists at all levels of the health care delivery system. Pursuant to authority delegated by the AOA, the AOCD oversees through its EEC the training of DO dermatology residents in AOA-accredited dermatology residency programs. The EEC of the AOCD makes its recommendations to the AOA’s PTRC which in turn reports to the AOA BOT. Under the ACGME, there are 26 specialty-specific committees, known as Residency Review Committees (RRCs), which periodically initiate revision of the standards and review accredited programs in each specialty and its subspecialties. The RRCs serve a role similar to that of the EEC within the AOCD. Whereas the EEC is ultimately subject to the oversight and authority of the AOA BOT, RRCs are part of the ACGME, an independent entity. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is a membership organization for dermatologists. The AAD’s website states “[t]he American Academy of Dermatology was founded in 1938. It is the largest, most influential and most representative dermatology group in the United States. With a membership of more than 17,000, it represents virtually all practicing dermatologists in the United States, as well as a growing number of international dermatologists.” The AAD offers Associate and Fellow membership to individuals who are eligible to take the American Board of Dermatology or the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada certifying examination in dermatology; International Fellow membership to dermatologists who reside outside the United States or Canada and who have obtained board certification approximately equivalent to that of the American Board of Dermatology; Affiliate membership to individuals who meet one or more of the following criteria: (1) DOs certified by the American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology, (2) MDs who are certified in dermatology by a non-U.S. or Canadian Board, and (3) board-certified dermatopathologists who are not eligible to be Fellows or Associates; and adjunct membership to various individuals who are not physicians. In contrast to the AOCD, the AAD has no direct role in accrediting, evaluating, or overseeing dermatology residency or fellowship programs. There are currently 27 AOA-accredited dermatology residencies, 119 osteopathic dermatology residents, and 469 Fellows of the AOCD. Additionally, there are three AOA-accredited Mohs fellowships and one AOA-accredited dermatopathology fellowship. Although early osteopathic postdoctoral dermatology training employed a preceptorship model, dermatology preceptorships were abolished in 1993. Since 1993, all AOA-accredited dermatology residency and fellowship programs have had a structure and curriculum similar to that of ACGME dermatology residency and fellowship programs. American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology The American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology (AOBD) was established by the AOA BOT in 1945 and operates under its authority. The AOBD is independent from the AOCD and submits its recommendations to the BOS for its consideration. The BOS ultimately forwards its recommendations to the AOA BOT for final review. The AOBD is charged with the following responsibilities: (1) To define the qualifications required of osteopathic physicians for certification in the field of dermatology, including those subspecialty areas of dermatology and any other specialty or field of practice that may be assigned to this board; (2) To determine the qualifications of osteopathic physicians for certification in the field of dermatology and of any other specialty or field or practice that may be assigned to it; (3) To conduct examinations in conformity with the bylaws, rules, and regulations of this board; (4) To issue certificates, subject to the approval of the Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists of the American Osteopathic Association, to those osteopathic physicians who are qualified; (5) To recommend revocation of certificates for cause; and (6) To use every means possible to maintain a high standard of practice within the osteopathic profession. Additionally, the AOBD accredits continuing medical education activities within osteopathic dermatology. In contrast to the ABD, the AOBD is not an independent body. The AOBD sends its recommendations to the AOA BOS for review. The BOS then sends its recommendation to the AOA BOT for final action. In contrast to the AOA, the AMA has no role in certifying or recertifying dermatologists. Osteopathic Continuous Certification As of January 1, 2013, each specialty certifying board, including the AOBD implemented requirements and procedures for Osteopathic Continuous Certification (OCC). DOs with timelimited board certification by AOA specialty certifying boards are required to participate in the five components of the OCC process in order to maintain their osteopathic board certification. The five components of OCC are as follows: Component 1 – Unrestricted Licensure: Requires that AOA-board-certified physicians hold a valid, unrestricted license to practice medicine in one of the 50 states. In addition, these physicians are required to adhere to the AOA’s Code of Ethics. Component 2 – Lifelong Learning/Continuing Medical Education: Requires that all recertifying physicians fulfill a minimum of 120 hours of continuing medical education (CME) credit during each three-year CME cycle — though some certifying boards have higher requirements. Of these 120+ CME credit hours, a minimum of 50 credit hours must be in the specialty area of certification. Self-assessment activities will be designated by each of the specialty certifying boards. Component 3 – Cognitive Assessment: Requires provision of one (or more) psychometrically valid and proctored examinations that assess a physician’s specialty medical knowledge as well as core competencies in the provision of health care. Component 4 – Practice Performance Assessment and Improvement: Requires that you engage in continuous quality improvement through comparison of personal practice performance measured against national standards for your medical specialty. Practice Performance Assessment modules are currently in development by the AOBD/AOA. Component 5 – Continuous AOA Membership: Membership in the professional osteopathic community through the AOA provides you with online technology, practice management assistance, national advocacy for DOs and the profession, access to professional publications, and continuing medical education opportunities Section V: Proposed plan for educating the AAD membership regarding the unification of AOA and ACGME dermatology training to increase its understanding of the house of medicine’s direction toward unity and to increase voting in favor of the bylaws amendment Plan concepts Educate several ACGME-trained dermatologists that are both political and thought leaders within the AAD on the Bylaw change to grant fellow status to DO dermatologists trained in AOA-accredited dermatology residency programs. Ask that current AAD political leadership (not AAD Board members) draft a brief message/editorial to be included in a daily AAD email and an article/editorial in upcoming issues of Dermatology World. Email and call all presidents of state dermatology societies and enlist their assistance in advancing the goals of the AHTF and educating their respective membership. We should ask state society presidents to place this item on their next meeting agenda. A brief PowerPoint presentation will be distributed to state dermatologic societies for presentation at one of their meetings prior to the 2015 AAD Annual Meeting. Identify a member of each state dermatologic society willing to deliver the presentation. Work with the AAD State Liaison Committee to facilitate. Start discussion on Derm Chat addressing the DO bylaw amendment. Speak with AAD members that have been especially vocal in their opposition to a bylaw change permitting AOA-trained dermatologists to attain AAD Fellow status to better understand and address their reasons for opposition. Create a panel session/forum for the 2015 Summer Academy Meeting to discuss the bylaw amendment. The discussion will focus on educating AAD membership on the similarity between AOA and ACGME training, performance of DOs in ACGME- and dually accredited dermatology residency programs, and the similarities between DO and MD medical education. Repeat the session at the 2015 AAD Annual Meeting (preferably at the beginning of Annual Meeting). Complete and submit publications. Timeline July 16 Aug. 4 Aug. 9 Aug. 13 Recommendation for Action (RFA) due to the Executive Office. PowerPoint presentation due for AAD Board Meeting. AAD Board Meeting Dr. Wisco and Dr. Messana to present. The AAD Board will vote whether to send the proposed amendment to the Bylaws Committee. Bylaws Committee Conference Call The Bylaws Committee will vote on the proposed amendment, based on 6 criteria. If the proposed amendment is approved by the Bylaws Committee, it will be 19 Aug. 2014 Sept. 2014 Oct. 2014 Nov. 2014 March 2015 referred back to the Board and they will vote whether to put the amendment on the 2015 ballot. Draft articles/editorials for Dermatology World Oct 2014 — Mar 2015 (6 articles). Draft JAAD/JAOCD Publication (use White Paper) — Plan to publish Jan 2015. Draft Member to Member Briefs. Initiate Derm World Online Video Interviews. Develop topics. Schedule interviews — goal for publication Jan 2015. Bylaw amendment announcement to full membership. The AAD will make an announcement to membership and call for pro and con statements (to be published in the ballot book). Up to 3 pro and 3 con statements will be published. The pro statements should be from prominent, respected members. Past presidents would be good but anyone currently on the Board cannot submit a pro statement. A letter from the Board supporting the amendment can also be published. Draft 4 or 5 sample letters for the Board’s choice. Start Derm Chat discussion on bylaw amendment. Roundtable session on DOs in dermatology at 2015 AAD Annual Meeting. AHTF Publications/Documents JAAD & JAOCD The current JAAD lag time is approximately three months from submission to print publication. Bruce Thiers, MD, FAAD, is editor. Dermatology World (DW) DW is the Academy’s primary non-scientific publication and is issued monthly. Abby Van Voorhees, MD, FAAD, is the physician editor. Publish pieces of white paper and editorials every month from October 2014 to March 2015 (6 issues). Member to Member The Academy's biweekly e-newsletter that provides an insider’s perspective on Academy programs and resources — as well as issues that affect the specialty — and highlights the unique benefits of being part of the AAD community. 20