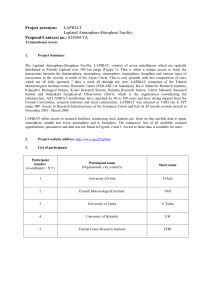

What were the features of `passive resistance` in the national self

What were the features of ‘passive resistance’ in the national self-determination movement in

Finland, 1899-1905?

CHANGE SLIDE!

FINLAND:

It is necessary to explore the peculiarities of Finland and its nationalism, prior to any investigation into the later movement for national self determination.

Following its separation from Sweden in 1807 and integration into the Russian empire, a phrase typifying the Finnish national position emerged: “we are no longer Swedes, we cannot become

Russians, let us then be Finns” 1 . From the start of the nineteenth-century therefore, the development of a Finnish national identity was an unorthodox one.

Once under Russian rule, Finland ‘enjoyed exceptional economic and cultural florescence and an exceptional degree of internal autonomy’ 2 . The impact of such freedom in the nineteenthcentury would only really be felt once it was infringed upon in the following century.

Finland was quite isolated from Russia in comparison to the other realms under its domain: o the Russian language was rarely spoken o Finnish schools and administration was estranged from that of the Russians o there was a high degree of local self-government.

Finland’s position would eventually lead to the tsar’s attempts at ‘Russification’, to integrate the state into the empire from 1899 onwards. Prior to this however, Finland’s peculiar nature led to the development of a nationalism quite distinct to that of the rest of Europe.

CHANGE SLIDE!

NINETEENTH-CENTURY NATIONALISM

1 Mikko Juva, p.30.

2 Alapuro, p. 111.

1

Risto Alapuro holds such an argument, generalising that western nationalism was generally the striving for a “civic religion”, whilst eastern was the liberation from second-class citizenship.

Finland on the other hand had ‘a nationalism in which both aspects - nationalism as protest of underdeveloped peoples and as civic religion - seem to have intertwined exceptionally closely’ 3 .

Nineteenth-century nationalism held cultural and linguistic focuses, as ‘from the individual’s point of view, full citizenship presupposes access to a common language and culture’.

4

Although ultimate power lay in St. Petersburg, dominance generally emanated not from the

Russians, but the Finnish Swedish-speaking elite. The elite did not necessarily identify themselves with Russia as they differed culturally to the metropolitan state as well as the majority of the Finnish speaking population. The elites of Finland were also comparatively weak to those seen throughout Europe, due to ‘the non-feudal class structure with a large and strong indigenous peasantry’ 5 . As a result, ‘in Finland not only the middle class but also the upper class had strong incentives for nationalist mobilization’ 6 .

CHANGE SLIDE!

Hence, the Swedish-speaking upper strata were in fact the main proponents of the nationalist movement, or Fennomania, in the 1840s and 1850s.

The Fennomans created the first Finnish mass organization, the temperance movement.

They aimed to create an upper-class culturally united with the majority of the people, stressing the need for linguistic reform, with liberation from Swedish cultural dominance and national self assertion.

3 Alapuro, p. 92.

4 Alapuro, p. 86

5 Alapuro, p. 91.

6 Alapuro, p. 85.

2

Despite facing some opposition from the liberal upper-classes who stressed Finland’s position as a separate political unit, ‘a comparatively united nationalistic culture among the upper classes and such middle-class groups as teachers and lower civil servants’ emerged.

7

Furthermore, by the end of the century, Finnish had achieved a strong position in the central institutional spheres of society.

Due to such developments in the nineteenth-century, once the process of ‘Russification’ begun, the intellectual terrain was well-prepared for the struggle for national self-determination, whether through passive or violent means.

CHANGE SLIDE!

RUSSIFICATION:

Various measures were passed by the tsar between 1899 and 1905 in an attempt to create a uniform administration, directly motivating the constitutionalists’ struggle for national self determination.

Under the surveillance of the governor-general of the Grand Duchy of Finland, N.I. Bobrikov, a detailed program for the administration and ‘Russification’ of Finland was enacted.

With the February Manifesto of 1899, ‘tsar Nicholas II made it clear that Finnish constitutional law was not to interfere with the policies of imperial integration or with any other matters affecting the interests of the Russian Empire as a whole’ 8 . The Manifesto essentially gave the tsar ‘the right to determine the final form of all legislation in Finland in matters of “general

Imperial concern”, while the Finnish Diet only had the right to give its opinion’ 9 , in 1899 enabling him to integrate Finland into the empire’s general system of military service.

7 Alapuro, p. 98.

8 Huxley, p 3.

9 Alapuro, p. 111.

3

For a state that had always felt itself reasonably autonomous under the Russian regime, such a

‘coup d’Etat’ understandably provoked a reaction, and due to its nationalist past, Finland had the ingredients ready for resistance.

As Mikko Juva dramatically depicts, ‘the February Manifesto of 1899 heralded the policy of

Russification. The Finns were astounded. The world had not yet seen Hitler and Nicholas II seemed like the Beast of the Apocalypse’ 10 .

Such legislation was followed by a host of other attempts at ‘Russification’: o Language Manifesto in 1900, extending the use of Russian in administration. o Conscription laws in 1901 assimilating the Finnish army into that of Russia. o Increased surveillance of Finnish educational institutions. o Abolition of Finland’s separate customs and monetary institutions and greater control of the Finnish press.

All helped to fuel the fight for national self determination, which was headed by a group of constitutionalists.

CHANGE SLIDE!

CONSTITUTIONALIST THEORY

This fight was the subject of much debate amongst the constitutionalists; the intellectuals’ response standing as an important feature of the overall struggle for national self determination.

There were various key thinkers on the matter, some of which helped take the initial stimulus of

‘Russification’ and apply it to a programme of passive resistance.

While there were a variety of attitudes towards ‘passive resistance’, themes can be drawn from the Finnish example.

10 Mikko Juva, in Finland an introduction, p. 33.

4

o Firstly, passive resistance was championed generally for practical rather than moral reasons. It was deemed ‘necessary for resistance strategy that the Finns be seen as the innocent victims of barbarian aggression’ 11 . o The importance of rank and file support was also stressed. o ‘Russification’ was explained as unjust, as it arguably infringed on Finnish laws ‘not merely in a narrow judicial sense, but also as the social order (including metaphysical and religious aspects) in general’ 12 .

Such justification for resistance on an intellectual level helped create a rhetoric of justice, necessary to the Finn’s struggle. As Steven Duncan Huxley explains, this was necessary as: ‘raw disobedience, noncooperation and defiance were foreign to Finnish culture.

Therefore in taking up these weapons the Constitutionalists sought to legitimize their use and convert the masses through an innovative ideology of justice which, however, could draw on

Finnish tradition’ 13 .

The Constitutionalists also attempted to convince the compliants of the need to resist. This was a particularly arduous task though, as they saw such action as futile, instead voicing what they labelled ‘political realism’.

As Finland was a strictly Lutheran nation, the masses also had to be convinced of the legitimacy of resistance to authority. Ironically this Lutheran base had been bolstered by Fennomania and revivalism, yet now stood as an obstacle to any mass nationalistic movement. The idea that it was a sin to surrender was championed in order to overcome such theological restrictions.

CHANGE SLIDE!

11 Huxley, p. 175.

12 Huxley, p. 157

13 Huxley, p. 168.

5

AVID VERNER NEOVIUS

Just one example...

Steven Duncan Huxley explains how Avid Verner Neovius, for example, believed that: passive resistance is not action as ordinarily conceived, rather it is systematic “refusal to act”, refusal to submit to, or cooperate in any manner with, violence (...for Neovius and his contemporaries the concept of violence was not confined to direct damage or harm caused to persons or things, but emphatically included injustice as well): To merely protest against injustice while at the same time submitting to the aggressor’s will is not, Neovius held, passive resistance, it is at best compliancy and, not rarely, treachery.

14

CHANGE SLIDE!

METHODS OF PASSIVE RESISTANCE:

The weight of Constitutionalist intellectual’s arguments, such as Avid Verner Neovius, ensured that the fight was waged using a plethora of ‘passive’ methods and tactics.

This is not to mean that there were no calls for violence however. As W.R. Mead explains,

‘although there was universal opposition to Russian intrusion, opinion was divided over the form that resistance should take’ 15 . The Finnish Active Resistant Party, for example, advanced all-out violence against the Russian regime. The predominant approach, however, remained ‘passive resistance’, materialising in many forms.

Upon Nicholas II’s 1899 reforms for example, there was an immediate response from Neovius, organising a petition to the Senate not to implement the alterations. 500 signed and yet the

Senate decided in favour of promulgation.

14 Huxley, p. 2.

15 Mead, p.144.

6

The Four Estates rejected such an action however, and as a result a symbolic ritual of daily decorating the statue of Alexander II in Helsinki with flowers began. This was an attempt to reemphasise to the Russian regime ‘Alexander’s promise to respect the Finnish constitution...a sacred compact between the sovereign and the people and the basis of Finnish self-rule’ 16 .

Protest on a much larger scale was also utilised, with 523,000 signing a petition in little over a week. This came to be known as the ‘Great National Address’, and involved half of Finland’s population, and yet it was still refused by the tsar.

There were also attempts to appeal for European support, with Constitutionalists writing articles in defence of Finland and encouraging their European colleagues to do the same. The document,

‘Pro Finlandia’ for example, pleaded the cause of the Finns and was signed by over 1000 eminent

European intellectuals, including Max Weber and Thomas Hardy. The Constitutionalist’s efforts however, were once again brushed aside by the tsar.

CHANGE SLIDE!

There were other forms of ‘grass roots’ protest, such as ‘draft dodging’ to act against the conscription laws, and the development of an underground resistance press.

The resistance press was also exceptionally important to the struggle as it was the ‘medium through which the conceptual or theoretical work on passive resistance was carried out’ 17 .

Various resistance newspapers were established, the two most prominent being the Fria Ord

(Free Words) and Vapaita Lehtisia (Free Leaflets). These violated Finno-Russian papers and censorship regulations whilst helping to disseminate a rhetoric of resistance against the Russian regime and to organise protest.

After Bobrikov forbade the use of Finnish stamps, for example, Fria Ord called on its readers to place protest stamps alongside the newly required Russian stamps. Furthermore, ‘officials

16 Max Jakobson, pp. 12-13.

17 Huxley, p. 150.

7

refused to obey illegal orders and the courts ignored laws and ordinancy promulgated on the basis of the February Manifesto and contrary to the constitution’ 18 .

CHANGE SLIDE!

DEAKEAN PARLIAMENTARY DEFIANCE

There was a shift in tactics however, with focus transferring to, what Huxley terms, ‘Deakean parliamentary defiance’.

Huxley argues that the low-point in resistance come between 1903 and 1904, with a fixity of theoretical and practical innovation in passive resistance. As a result, by the end of 1903,

Constitutionalists were looking for new ways to invigorate the movement once more.

There was a ‘shift of emphasis from the struggle for justice...to the popular struggle for freedom.

Similarly the resisters increasingly realised the necessity of democratic reform and collaboration with working people’ 19 .

With Borbikov’s assassination in June 1904, his replacement by the more moderate I.M.

Obolensky, and the tsar distracted by his problems in the Far East, the Finnish Diet was allowed to reconvene and exiles return. ‘Elections provided the Constitutionalist front a chance to surface from the underground passive resistance, and shift the struggle into a legitimate institutional framework’.

20 The landslide electoral victory that ensued ensured the Diet was now in Constitutional hands and actions against ‘Russification’ could forge on.

CHANGE SLIDE!

18 Mikko Juva, p. 34.

19 Huxley, p. 242.

20 Huxley, p. 243.

8

GENERAL STRIKE

The greatest action, however, came with the General Strike of 1905, spreading from Russia and its empire in October of that year. In this instance, another important element of the passive resistance to ‘Russification’ comes to light; the involvement of the social democrats. In early

1905 the rank and file challenged the legitimacy of the now Constitutionalist Diet, convinced no efforts were being made to achieve their demands of universal suffrage. As a result, Finnish labour forces took the initiative, implementing a nationwide strike.

The country was paralysed, and hence ‘the emperor authorized the transformation of the political system on 4 November 1905, together with the suspension of the February Manifesto, the conscription law, and other integration measures’ 21 .

Constitutionalists took over the domestic government; the Senate ‘drafted a Parliamentary Act and an election law, passed by Diet on 29 May 1906 and confirmed by the tsar on 20 July 1906, thus abolishing the fundamental political organ and relic of the old status society, the Diet of

Four Estates’ 22 .

The Social Democratic working-class movement was not to fully flourish into a mass movement until 1906, yet between the years of 1899 and 1905 it was a sufficient enough force to be considered a feature, all be it embryonic, of the national self determination movement. Workers can be seen to have interacted with Constitutionalists in the temperance movement, which was seized by the Fennoman elite in order to achieve national integration of the workers.

CHANGE SLIDE!

WIDER CONTEXT

21 Alapuro, p. 115.

22 Huxley, p. 247.

9

The struggle for national self determination that Finland witnessed must also be contextualised in other manners in order to understand its various features completely.

The upheavals of 1905 were certainly interlinked with the Russian Revolution, the mass of political tension that disseminated throughout the empire.

As Huxley explains, the Finnish resistance, whether willing or not, through passive resistance became ‘active participants in a broader potentially revolutionary process’ 23 . Michael Randle seconds such an opinion, stating that the Finnish movement ‘received unlooked-for assistance in the shape of the 1905 revolution in Russia, and the Empire-wide general strike’ 24 .

However, although linking the two phenomena, Huxley concludes that: ‘up until its end, the

Finnish resistance movement remained primarily a separate and particularistic affair; it was a separate part of an Empire-wide revolutionary process and the resistance leaders aimed to keep it that way. This is one of the main reasons why the Finnish Constitutional front stuck to its strategy of passive resistance’ 25 .

We can also see how the wider context had implications for the success of the Finnish movement. Mead highlights two external influences affecting the General Strike in Finland, for example:

‘The climax coincided with the ill-conceived Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905. The war, in turn, was accompanied by exceptional domestic stresses in Russia; they were reflected in

Finland in a general strike in 1905. In the face of both external and internal pressures,

Russia’s grip on Finland was relaxed’ 26 .

23 Huxley, p. 209.

24 Randle, p. 39.

25 Huxley, p. 223.

26 Mead, p. 144.

10

The Hungarian movement for national self determination is also worthy of note. It undoubtedly influenced the Finnish equivalent, acting as ‘the prototype for the Finnish passive resistance to attempted Russification from 1899-1906’.

27

Arguably even influencing the most renowned of ‘passive’ action; Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle for Indian independence.

Therefore, when analysing the features of ‘passive resistance’ in the national self determination movement, it should not be overlooked that one is also analysing wider issues.

27 Randle, p. 39.

11