File

advertisement

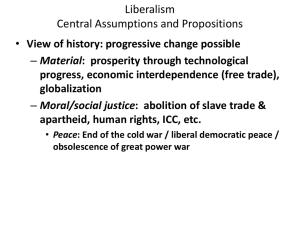

Alexa Toole RPOS 370 Theoretical Critique 1 24 March 2014 There are various types of theories when it comes to the topic of international relations. The focus of this particular theoretical critique is liberalism. Liberalism is a theory unlike any other because it focuses on that state-society relations have a fundamental impact on a state’s behavior.1 Unlike a realist, a liberalist would view that what matters most in world politics are the states preferences.2 Liberalists believe that what comes first is that you have to know what the states want. Because liberalism has put emphasis on the ties between states, military power has been decreased and it has been challenging to define what national interest is. Liberalism does not look at military power as being the only power. Liberalists view economic power and social power as being important as well. It is also proven that using economic power is more beneficial than using military power. Liberalists believe that when a state uses its military power it is not always beneficial either. They want the states to have international cooperation, not conflict. The theory of liberalism believes that different states possess different interests among them. A way to help keep states close even though they have different primary interests is by implementing international organizations and rules. Most realists would conclude that liberalism is somewhat idealistic. Liberalism, most importantly, has an optimistic view of the world, and Andrew Moravcsik, “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics”, International Organization 51 (1997): 513. 2 Ibid., 513. 1 that collective cooperation among the states is actually possible. A key assumption of liberalism is that cooperation among states can be beneficial for all states and produce gains. There are three core assumptions of the liberal theory. The first assumption is the primacy of societal actors. This assumption basically states “the fundamental actors in international politics are individuals and private groups, who are on the average rational and riskaverse and who organize exchange and collective action to promote differentiated interests under constraints imposed by material scarcity, conflicting values, and variations in societal influence”.3 In other words, the liberal theory is viewed from the “bottom-up” of politics.4 Societal actors and their interests for liberals are central, but I believe that this is a utopian way of looking at it. Liberals think that states all have the same interests and that somehow brings about peace. This is not necessarily a reality because states are continuously engaging in conflicts for disagreements over interests. The second assumption is representation and state preferences. This assumption says “states (or other political institutions) represent some subset of domestic society, on the basis of whose interests state officials define state preferences and act purposively in world politics”.5 Essentially, liberals view the state as a representative, not an actor.6 I agree with the liberalist idea that “no government rests on universal or unbiased political representation; every government represents some individuals and groups more fully than others”.7 That statement certainly applies to reality. There is the goal of equal representation but, in actuality, it does not happen that way. The third and final assumption is Andrew Moravcsik, “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics”, International Organization 51 (1997): 516. 4 Ibid., 517. 5 Ibid., 518. 6 Ibid., 518. 7 Ibid., 518. 3 the interdependence and the international system. This assumption states, “the configuration of independent state preferences determines state behavior”.8 I find this assumption to be very complex and confusing. It is not clear to me that state behavior is sort of defined by its preferences. Only the second assumption on representation could actually be applied in reality. The first and the third are so complex and idealistically viewed that it is not positive they could be imposed on reality. It does matter whether the assumptions of the liberal theory can be applied because that makes the liberalism complete; and without it sort of leaves “holes” in the liberal theory overall. The liberal theory’s quality can be evaluated in the seven dimensions of logical consistency, completeness, explanatory and predictive power, parsimony, empirical validity, substantive significance, and prescriptive richness. The liberal theory, I believe, is not found to be logically consistent. It discusses the idea of competing states that essentially all want peace but it is not coherent. According to Rathburn, liberalism does not possess any type of coherent logic of its own.9 Rathburn does not even believe that liberalism has a core to start with, and that it’s independent variables are not connected.10 The completeness of the liberal theory is somewhat poor. As previously stated, the assumptions of the liberal theory are not easily applicable to actual reality. The liberal theory leaves room for error indefinitely. It relies too much of the societal actors and not as much on the political actors which decide much of the “peace” that liberalists want to see. Andrew Moravcsik, “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics”, International Organization 51 (1997): 520. 9 Brian C. Rathburn, “Is Anybody Not An (International Relations) Liberal?”, Security Studies 19 (2010): 5, accessed March 20, 2014, doi: 10.1080/09636410903546558. 10 Ibid., 4. 8 The explanatory power of the liberal theory is concise, while the predictive power is not. The theory goes through and explains its assumptions however realistic they may be. It also explains how peace among the states is obtained even though it may not actually happen. But the idea that states with similar interests preserves this peace in not accurate. Liberalism incorporates domestic politics, which right then and there does not make it a strong international relations theory.11 It does not apply to all the states like it idealistically wants to. The liberal theory may explain the democratic peace theory, but it cannot be used to explain anything else such as the factors for the First World War. According to Moravcsik, “liberalism generates many empirical arguments as powerful, parsimonious, and “efficient” as those of realism”.12 Rathburn would most likely disagree because this goes back to the idea that liberalism does not have an actual core, therefore how can it be parsimonious and empirically valid. The liberal theory does have a substantive significance to it with the idea of peace, but as previous stated it is not concise and cannot be applied to all states solely on the fact that liberalism agrees with domestic politics. As far as the liberal theory’s prescriptive richness, the complexity of the theory itself takes anyway from its meaning. It tries to explain so much that I feel it lacks much comprehension from those trying to understand it. The liberal theory’s main idea, I believe, is admirable. The idea of trying to preserve peace among the states, and leave war to the last possible outcome is a good way to see how the world should be. Scholars and policymakers should not use this theory to understand Brian C. Rathburn, “Is Anybody Not An (International Relations) Liberal?”, Security Studies 19 (2010): 4, accessed March 20, 2014, doi: 10.1080/09636410903546558. 12 Andrew Moravcsik, “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics”, International Organization 51 (1997): 533. 11 international politics. Liberalism is too idealistic, and does not have a collective way to bring out peace among states. The liberal theory only addresses how the world should be, not how it actually is. References Moravcsik, Andrew. (1997). Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics. International Organization, 51, 513-553. Rathburn, Brian C. (2010). Is Anybody Not An (International Relations) Liberal? Security Studies, 19(1), 1-25. doi: 10.1080/09636410903546558