File - Books "Ain`t" Really Books

advertisement

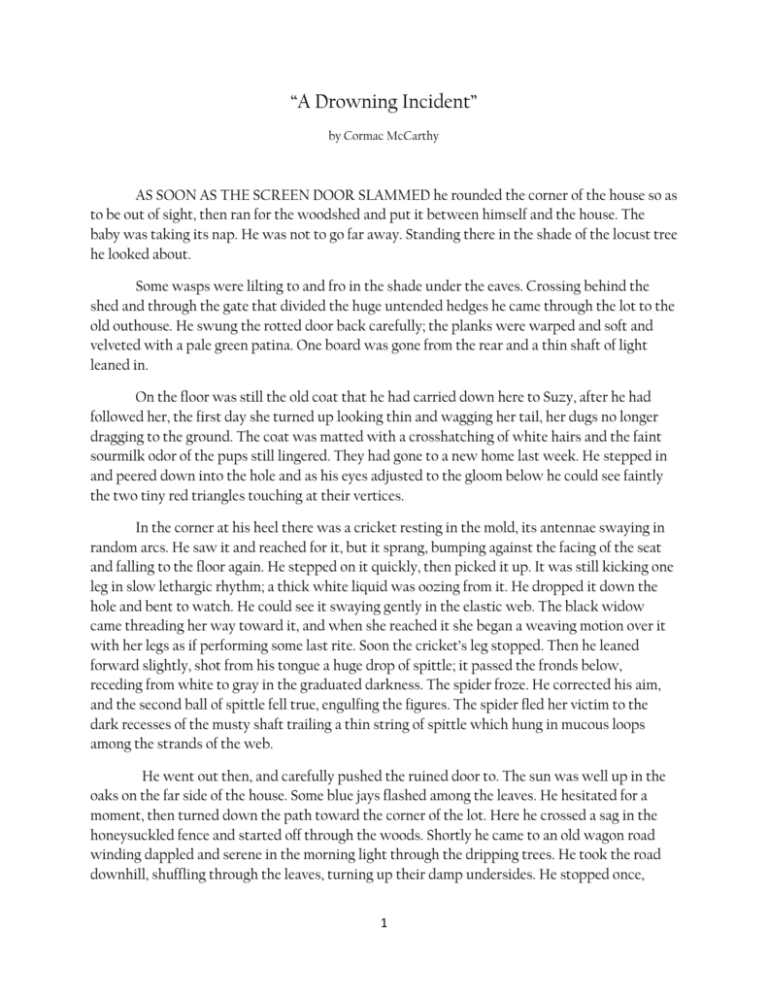

“A Drowning Incident” by Cormac McCarthy AS SOON AS THE SCREEN DOOR SLAMMED he rounded the corner of the house so as to be out of sight, then ran for the woodshed and put it between himself and the house. The baby was taking its nap. He was not to go far away. Standing there in the shade of the locust tree he looked about. Some wasps were lilting to and fro in the shade under the eaves. Crossing behind the shed and through the gate that divided the huge untended hedges he came through the lot to the old outhouse. He swung the rotted door back carefully; the planks were warped and soft and velveted with a pale green patina. One board was gone from the rear and a thin shaft of light leaned in. On the floor was still the old coat that he had carried down here to Suzy, after he had followed her, the first day she turned up looking thin and wagging her tail, her dugs no longer dragging to the ground. The coat was matted with a crosshatching of white hairs and the faint sourmilk odor of the pups still lingered. They had gone to a new home last week. He stepped in and peered down into the hole and as his eyes adjusted to the gloom below he could see faintly the two tiny red triangles touching at their vertices. In the corner at his heel there was a cricket resting in the mold, its antennae swaying in random arcs. He saw it and reached for it, but it sprang, bumping against the facing of the seat and falling to the floor again. He stepped on it quickly, then picked it up. It was still kicking one leg in slow lethargic rhythm; a thick white liquid was oozing from it. He dropped it down the hole and bent to watch. He could see it swaying gently in the elastic web. The black widow came threading her way toward it, and when she reached it she began a weaving motion over it with her legs as if performing some last rite. Soon the cricket’s leg stopped. Then he leaned forward slightly, shot from his tongue a huge drop of spittle; it passed the fronds below, receding from white to gray in the graduated darkness. The spider froze. He corrected his aim, and the second ball of spittle fell true, engulfing the figures. The spider fled her victim to the dark recesses of the musty shaft trailing a thin string of spittle which hung in mucous loops among the strands of the web. He went out then, and carefully pushed the ruined door to. The sun was well up in the oaks on the far side of the house. Some blue jays flashed among the leaves. He hesitated for a moment, then turned down the path toward the corner of the lot. Here he crossed a sag in the honeysuckled fence and started off through the woods. Shortly he came to an old wagon road winding dappled and serene in the morning light through the dripping trees. He took the road downhill, shuffling through the leaves, turning up their damp undersides. He stopped once, 1 stripped off a handful of rabbit tobacco, stuffed it in his mouth and shuffled down the road, spitting, his thin shoulders rolling jauntily. The road angled and switchbacked down the hill until it came to the edge of the woods where it straightened briefly before losing itself in the humming field beyond which stretched the line of willows and cottonwoods that marked the course of the creek. He could still feel the ruts beneath his feet as he waded through the knee high grasses or threaded among the sporadic blackberry brambles. Then he was parting the screen of willows, lime and golden as they turned in the sun with his passage. He could hear the faint liquid purling even then, even before he emerged from the willows where the bridge crosses, glimpsed through the green lacework the fan of water beyond where the sun broke and danced on the stippled surface like silver bees. He walked out onto the little bridge, stepping carefully. The curling planks were cracked and weathered, bleached an almost metallic grey. The whole affair bellied dangerously in the middle like a well used mule. He sat down on the warm boards, then stretched out on his stomach and peered over the edge into the water below. The creek was shallow and clear. The floor of the pool was mottled brown and gold as a leopard’s hide where the sun seeped through the leaves and branches overhead. Minnows drifted obliquely across the slow current. Through the water-glass he watched the tiny shadows traverse the leopard’s back silent and undulant as a bird’s flight. He found some small white pebbles at his elbows and dropped them to the minnows; they twisted and shimmered slowly to the bottom trailing miniscule bubbles that stood in brief tendrils before rising and disappearing. The minnows rushed to inspect. He folded his arms beneath his chin. The sun was warm and good on his back through the flannel shirt. Then with the gentle current drifted from beneath the bridge a small puppy, rolling and bumping along the bottom of the creek, turning weightlessly in the slow water. He watched uncomprehendingly. It spun slowly to stare at him with sightless eyes, turning its white belly to the softly diffused sunlight, its legs stiff and straight in an attitude of perpetual resistance. It drifted on, hid momentarily in a band of shadow, emerged, then slid beneath the hammered silver of the water surface and was gone. He sat up quickly, shook his head and stared into the water. Minnows drifted in the current like suspended projectiles; a water-spider skated. They were black and white, they were black and…except for the one black all over. He crossed the bridge and started after it, then stopped. When he turned his eyes were wide and white. He came back and started up the creek along the path that curved above the low cutbanks. He studied the water as he went. Small riffles ran through aisles of watercress awash and flowing in the stream, along rocks where periwinkles crowded. A crawfish shot beneath the looped bole of a cottonwood. In one pool an inexplicable shoe sat solemnly. At the bend in the creek just below where it passed beneath the pike bridge the current swirled faster and the following pool was deep. Because of the turn the creek made, the sun was 2 now in his eyes and he could not see into the water. He hurried to the pike, crossed the small concrete bridge, and worked his way down the other side, through a stand of cane. When he reached the creek he was on a high bank; below him the current rocked in a swift flume, the water curling and fluted. Below this, in the amber depths of the pool, he could make out a dark burlap sack. He sat down slowly, numb and stricken. As he stared, a small head appeared through a rent in the bag. It ebbed, softly for a moment, then, tugged by a corner of the current, a small black and white figure, curled fetally, emerged. It was like witnessing the underwater birth of some fantastic subaqueous organism. It swayed hesitantly for a moment before turning to slide from sight in the faster water. He had no tears, only a great hollow feeling which even as he sat there gave way to a slow mounting sense of outrage. He stood up then, and pulled down a long willow limb and worked it back and forth across his knee trying to worry it in two, but it was tough and resilient and after a while he gave it up. He made his way back through the canes to the road and to the other side where there was a fence. He followed it until he found a loose strand in the wire. This he pulled out, and with a few bendings the rusty latter end came free. He went back to the creek and with the wire hooked at the end tried to fish up the sack from the bottom of the creek. The wire was too long to control, and the current would sweep it away; it was nearly half an hour before he hooked the sack. He twisted the wire in his hand, and when he pulled it the sack followed, heavy and sluggish. He worked it to the bank and lifted it gingerly to shore. It was rotten and foul. When he opened it there was only one puppy inside, the black one, curled between two bricks with a large crawfish tunneled half through the soft wet belly. He hooked his wire into the crawfish and pulled it out, stringing behind it a tube of putrid green entrails. He tried to push them back inside with the toe of his shoe. He went to the road again and scouted the ditches alongside until he found a paper bag, which he brought back and into which with squeamish fingers he deposited the tiny corpse. Then he pushed through the heavy brush until he came to the field, crossed at a diagonal, and entered the woods just a few yards short of the wagon road. He turned up the road swinging the dirty little bag alongside. His steps were trance-like and mechanical, his eyes barren. When he reached the house Suzy came trotting across the yard to meet him. He avoided her and went in by the back door, closing it carefully behind him. In the kitchen he stopped and listened. The house was silent; he could hear his heart thumping. A warmthless light filled the panes of glass above the sink. Then he heard her cough—she was always coughing—and listened closer. She was in the bedroom. He listened at the door, then quietly eased it open. The shades were drawn, and where the sun beat against them they were suffused with a pale orange glow which permeated the air, air infested with the faint urinous odor of the baby, the odor of the blankets, sensuously fetid and intimate. He stood in the doorway for an intenuinable minute. What prompted his next action was the culmination of all the schemes half formed not only walking from the creek but from the moment the baby arrived. Countless rejected, revised, or denied thoughts moiling somewhere in 3 the inner recesses of his mind struggled and merged. He lifted the stinking bag and looked at it. It was soggy and through a feathered split in the bottom little black hairs protruded like spiderfeet. Afterward, thinking about it, it did not seem him that crossed the room to the crib in the corner, lifted back the soft blue blanket, and alongside the sleeping figure, small and wrinkled, dumped the puppy and then folded the blanket over them. He remembered vaguely seeing the green entrails oozing onto the sheet as the blanket fell. He is waiting for him to come home now; it is almost dinner time. He is sitting on his bed, his mind a dimensionless wall against which only a grey pattern, whorled as a huge thumbprint, oscillates slowly. His mother went once to the room quietly, but the baby did not wake. He is waiting for him to come home. (1960) 4