The Divine Right to Rebel

advertisement

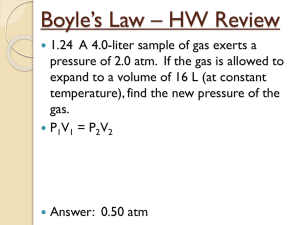

The Divine Right to Rebel The very un-Civil Wars and the Execution of Charles I ‘What is a Rebel? A man who says no.’ Albert Camus By Anne Reynolds I feel frustrated when people assume I have a rebellious nature just because I ran away from home at the age of 17. It seems to me the obvious, non-violent response to injustice and emotional abuse. In a similar vein I can recall regularly walking out, or remaining seated, as the national anthem was played in the Gerrards Cross ‘flea pit’ at the end of a film. It was ridiculous to expect people to stand to attention like puppets just because of a bit of music and anyway why should I? Just because the famous ballet dance mistress, Madame Vacani, had taught me the royal curtsey didn’t mean I was ready to use it. Class discrimination and deference were departing from postwar Britain faster than a slug in a stream of salt but that didn’t mean there were not some entertaining skirmishes between ardent monarchists and those of us who were burgeoning socio-political protesters. Bob Dylan echoed this sense of turmoil in his 1964 album title track, The Times They are a-Changin: ‘As the present now Will later be past The order is Rapidly fadin’ And the first one now Wil later be last For the times they are a-changin.’ This is the salutary tale of what can happen to you when you listen to your own hype and ignore the winds of change – even if you are a King. Three hundred and sixty-three years ago, on a bitterly cold January day in 1649 when even the river Thames had frozen over in protest, we, the people of England, cut off the head of King Charles I in one swift sweep of the executioner’s axe just before 2pm. I must confess that I feel really queasy when I write that down; if you think about the reality of what it involves, it is unarguably gruesome. In historical terms it’s not that long ago and even though public executions were fairly commonplace in London at that time, the despairing groan from the crowd, as his head was held up for inspection, was in sharp contrast to the usual loud cheers and jeers. And this was despite the Cromwellian troops deployed around the temporary scaffolding set up outside the Banqueting House, in order to prevent unseemly outbursts from the spectators. The usual ‘behold the head of a traitor’ was left unsaid although he had been convicted 1 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 of ‘High Treason and other high Crymes’ by what can only be described as a highly-tampered-with jury; all those who would have opposed such a verdict having been expelled from the High Court of Justice beforehand. Some of the 59 signatories to the death warrant would pay with their own lives on the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Those who had died in the interim did not escape as they were exhumed and executed nonetheless. Can you spot the surname of one of your ancestors in this list of regicides? Jo Bradshawe; Tho. Grey; O. Cromwell; Edw. Whalley; M. Livesey; John Okey; J. Da[n]vers; Jo. Bourchier; H. Ireton; Tho. Mauleverer; Har. Waller; John Blakiston; J. Hutchison; Willi. Goffe; Tho. Pride; Pe. Temple; T. Harrison; J. Hewson; Hen.Smyth; Per. Pelham; Ri. Deane; Robert Tichborne; H. Edwardes; Daniel Blagrave; Owen Rowe; Willm. Purefoy; Ad. Scrope; James Temple; A. Garland; Edm. Ludlowe; Henry Marten; Vinct. Potter; Wm. Constable; Rich. Ingoldesby; Willi. Cawley; Jo. Barkstead; Isaa. Ewer; John Dixwell; Valentine Wauton; Symon Mayne; Tho. Horton; J. Jones; John Moore; Gilbt. Millington; G. Fleetwood; J. Alured; Robt. Lilburne; Will. Say; Anth. Stapley; Greg. Norton; Tho. Challoner; Tho. Wogan; John Venn; Gregory Clement; Jo. Downes; Tho. Wayte; Tho. Scot; Jo. Carew; Miles Corbet. An extract from The Death Warrant of King Charles I in the House of Lords Record Office, Memorandum No 66. Of course, being answerable only to God, Charles naturally did not recognise the legitmacy of the court and refused to defend himself or remove his hat. The judge, John Bradshaw, didn’t remove his hat either but that was because he feared for his life. In rather Ned-Kelly-esque style he had metal inserted inside the hat and wore armour under his clothes to protect himself from attack. If you visit Windsor you can find the Old King’s Head pub (just a short walk away from the Castle, opposite Church Street Gardens), which displays a replica of King Charles’ death warrant on its frontage. I live in the beautiful Chilterns, a short walk away from ‘The Royal Standard of England’, which claims to be the oldest freehouse in England. Charles II rewarded the inn for its support to the royalists by changing its name from ‘The Ship.’ Rumour has it that another reason for this generous gesture was because the King used to have assignations with one of his mistresses in an upstairs room. Its past history makes it attractive to tourists who like to hear the gory story of the 12 cavalier heads on spikes, one of which belonged to a 10 year old drummer boy whose ghost is said to haunt the pub to this day (www.rsoe.co.uk). That this period in history is still of great interest was confirmed when a rare 1651 ‘wanted’ poster issued for the capture of Charles II - sold at auction for £33,000.00 in March 2012, well in excess of the guide price of £700-£1,000. The poster declared that a reward in the princely sum of £1,000.00 would be paid: 2 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 ‘FOR THE Difcovery and Apprehending of CHARLS STUART, AND OTHER Traytors His Adherents and Abettors.’ Trafalgar Square: The Heart of England At the curve of the river Thames, where today the Strand meets Trafalgar Square, a natural junction emerged, which came to be known as Charing Cross. On the site where the Charles I equestrian statue now stands on its own traffic island, south of Trafalgar Square, a memorial cross was erected by King Edward I to his beloved Queen Eleanor who fell sick and died in 1290. Many years afterwards Edward referred to Eleanor as she ‘whom living we dearly cherished, and whom dead we cannot cease to love.’ The Eleanor cross was demolished during the Interregnum, in 1647, for being ‘idolatrous’. A replica of the cross was erected in 1863 outside Charing Cross station. As I move through the milling crowds in Trafalgar Square on an unseasonably sunny February day, I am aware of the spirits of the past, moving in sepia outlines between the tourists who are oblivious to their presence. I have conjured up the children enthralled by the punchinello shows, the pickpockets, pillory, carts and carriages, flower sellers and, of course, the noxious stench of a growing, bustling City. This is the place where several of the regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered at the Restoration of the Monarchy. Did you know that all road signs showing the number of miles to London are measured to the statue of Charles I? This makes it the heart of England and a place shimmering with the past as unseen threads from all over the country link to this one spot. It is unsurprising then that it is also the meeting point for several ley lines and is the perfect place for a spot of dowsing. 3 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 ‘Powerless Structures, Fig 101 (Elmgreen & Dragset)’ is a sculpture of a boy astride his rocking horse. A child has been elevated to the status of historical hero, though there is not yet a history to commemorate – only a future to hope for. Cast in bronze, the work references the traditional monuments in the square, but, with its golden shine, it celebrates generations to come…Tell us what you think at www.london.gov.uk/fourthplinth MAYOR OF LONDON. King Charles I 1625-1649 This bronze statue was made in 1633 for Lord Treasurer Weston by Hubert Le Sueur. It was acquired for the Crown and set up here in 1675. The carved work of the pedestal being executed by Joshua Marshall. The fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square is currently occupied by ‘Powerless Structures’ and it’s nice to be asked by Boris Johnson to envisage a better future for us all. But, as Niccolò Machiavelli accurately observed, ‘history is written by the victors’ and I think that is the ‘elephant in the room’ as far as the history of the Charles I statue is concerned. I watched confused tourists scanning it for a narrative plaque and walking straight over the uninformative one set in the pavement. Some even bent down to read the card attached to the wilting wreath ‘From the officers and members of the Royal Stuart Society, Aymez Leyaulte’ (‘love and loyalty’) but looked just as baffled afterwards. Two important strands in history have become entangled here: (1) a growth spurt in the development of democracy in England (the origins being Magna Carta in 1215) and the consequent shift in the balance of power from monarch to government; and (2) the execution of a Stuart monarch, followed in due course by a permanent change from the Stuarts to the House of Windsor. I’m not suggesting there is an active conspiracy but, over generations, if certain things are not discussed they vanish from the foreground. The statue’s plinth has two plain sides and these show signs of what appear to be dowel holes that would probably have supported a descriptive tablet. (My guess is that it would have said something along the lines of ‘Stuarts for ever!’). All my efforts to locate the wording have failed and after initial frustration I now accept that my requests are unlikely to be met with any enthusiasm. I did have one breakthrough when I located a drawing of it at the British Library dated 1740. Text of some kind was clearly indicated on the plaque. My instinct tells me that in an age where printed communication was limited and there was neither television nor the internet, public symbols really mattered. In 1660 bonfires blazed across London in celebration of Charles II’s return to London and the words ‘The last tyrant of kings died in the first year of liberty of England restored’ were removed from a 4 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 bust of Charles I. As Samuel Pepys – who had witnessed the death of Charles I as a schoolboy recorded: ‘The writing in golden letters, that was engraven under the statue of Charles I, in the Royal Exchange was washed out by a painter, who in the day time raised a ladder, and with a pot and brush washed the writing quite out, threw down his pot and brush and said it should never do him any more service, in regard that it had the honour to put out rebels’ hand-writing.’ James I 1603-1625 I Charles I 1625-1649 I Cromwell’s Interregnum 1649-1660 I Charles II 1649 (or 1660)- 1685 I James II 1685-1688 (fled to France) I William of Orange & Mary 1689-1702 These wreaths were laid on 30 January 2012, the anniversary of King Charles I’s execution. It is no accident that the white rose of the Jacobites* is included in all three of the wreaths. The Jacobites supported the Stuarts’ claim to the English throne after James II was replaced by William of Orange and Mary. Franz, Duke of Bavaria is the current Jacobite heir. On his death, the ultimate heir will be Prince Joseph Wenzel Maximilian Maria of Liechtenstein who is currently attending Malvern College in Worcestershire. He is the first ‘pretender’ to have been born in England since James II left the country in 1688. The website of the Royal Stuart Society declares that: ‘It should be noted that none of these representatives of King Charles I since 1807 has attempted to claim a British Throne…Under the terms of the Act of Settlement (1701) they have all been excluded from the de facto line of succession which vests in the present House of Windsor.’ * The term ‘Jacobite’ is derived from the Latin word Jacobus, meaning James and was coined during the reign of King James I & VI. http://www.royalstuartsociety.com That’s all fascinating stuff but I think I can safely say there’s no imminent threat of a counter-claim to the British throne so why not tell passers-by the fascinating story of the statue? It’s the oldest one in London having been cast in bronze in 1633 at a cost of £600. The metal is half an inch thick and it took 8 months to create. The horse, a Flemish long tail, is 7’8” high riderless. The King is shown as 5 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 being 6’ and that is about 1’ taller than he was in reality. Over the years it has lost numerous swords, buckles and straps and the ‘George’ (Order of St George) disappeared in 1844. It was entirely encased in sandbags during the Great War and removed for safe keeping to Mentmore Towers, Buckinghamshire during WWII. I can’t help feeling a little sorry for him as he perpetually stares down Whitehall towards the scene of his death, of which only Inigo Jones’ Banqueting House remains, and away into the distance towards Big Ben. Lovers kiss, oblivious to the history swirling around them. A jogger runs over the crossing while the 453 to Marylebone waits for the red light to change. The statue was originally on display in Sir Richard Weston’s garden at Roehampton. It was confiscated by Parliament in 1644 and subsequently sold for £150 to parishioners of the Church of St Paul’s, Covent Garden who erected it in their churchyard. In 1650 the Council of State ordered all owners of royal statues to destroy them but no owner could be traced for the statue in St Paul’s, so Parliament sold it to John Rivett, a brazier of Seven Dials. He was ordered to melt it down and subsequently sold knives whose handles he claimed to have been made from the statue. Commercially he couldn’t lose because monarchists would have valued the items as mementos and puritans would view them as symbols of victory over a tyrant king. The truth was that he buried the statue and all the knives sold were fakes. His motivation is lost in the annals of time but at the Restoration of the monarchy, Rivett dug up the statue and was appointed to the Office of King’s Brazier. The statue was eventually purchased by Charles II in 1675 when it was erected on the site of the old Eleanor Cross. Art for Art’s Sake or Propaganda? Charles I gathered together one of the finest art collections ever seen in England but it’s also clear that, like many of his predecessors, he was acutely aware of how important image was in the public relations of the time. It was his engagement of Anthony Van Dyck as ‘principalle Paynter in ordinary to their majesties’ that allowed him to indulge in the spin doctoring necessary to inflate his image. A diminutive figure with a pronounced stammer and a strong Scottish accent, he needed to reinforce his kingly status by demonstrating his power and importance. His older brother, Henry, had been a charismatic and popular figure who died of typhus in 1612. It would be difficult for this unimpressive younger brother to step into his riding boots. This magnificent Equestrian canvas of Charles I (1637-8), which measures 367 x 292 cm, hangs in the Mond Room at the National Gallery. This painting is also known as the ‘wandering portrait’. When Parliament ordered the dispersal of Charles I’s art collection after his execution, it was first bought by Balthazar Gerbier and then passed through the hands of several European princes before arriving back in England as the ‘spoils of war’. It was given to the Duke of Marlborough whose descendant sold it to the National Gallery in 1885. It was briefly evacuated for safe keeping during WWII to a slate quarry in Wales. 6 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 The Final Hours The night before his execution, Charles slept at St James’ Palace with his faithful attendant, Thomas Herbert, on the floor beside him. The next morning Bishop William Juxon prayed with him and administered the sacrament in the Chapel Royal. Accompanied by Juxon and Herbert, he walked across St James’ Park along a route guarded by two companies of infantry. After passing over the upper floor of the Holbein Gate (where they would have seen the black-draped scaffold), they entered Banqueting House. In 1649, Parliament proclaimed that ‘the office of the king in this nation is unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, society and public interest of the people.’ He had requested two shirts to protect him from the cold in order that people would not think him to be shaking from fear. As I followed in his footsteps I wondered if he had any last-minute regrets. If he did I suspect he kept them to himself. Although the manner of his death was out of his hands, he was able to choreograph the public face of his departure. He would have been gratified to know that Andrew Marvell, a Parliamentarian at heart, wrote ‘An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland’ in 1650, which included a reference to the dignified way in which Charles met his death the year before: ’That thence the royal actor borne The tragic scaffold might adorn, While round the armed bands Did clap their bloody hands. He nothing common did or mean Upon that memorable scene, But with his keener eye The axe’s edge did try; Nor call’d the gods with vulgar spite To vindicate his helpless right, But bowed his comely head Down as upon a bed.’ There was a delay before the execution took place as the Hangman, Richard Brandon, refused to carry out the sentence. When the executioner and his assistant finally appeared 3 hours later, they were in disguise and masked in order to avoid identification. Some say Brandon did carry out the execution but no one knows for sure. What is certain, however, is that whoever dealt the fatal blow was highly experienced in his trade. The King was calm and composed. His short speech was taken down by a couple of shorthand writers and you can read the full text here http://anglicanhistory.org/charles/charles1.html. Juxon helped the King to tuck his long hair into a cap so that it might not impede the axe. Charles replied, ‘I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be, no 7 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 disturbance in the world.’ He then passed his diamond-encrusted George to Juxon and said one word, ‘Remember!’ It is possible that his treasured George was destined for his son, Charles. The King's embalmed body, with the severed head stitched back on, lay on display in Whitehall and the royal apartments at St James' Palace for several days. It was important for people to know that he was truly dead. On the other hand, Cromwell did not want his burial place to become a shrine and refused to allow him to be laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. Eventually, it was agreed that the body would be released to Bishop Juxon and other supporters for a private burial in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. It was decided to lay him to rest in a vault containing the remains of King Henry VIII, Queen Jane Seymour and a stillborn child of Queen Anne. The white snow that fell in a flurry as the funeral party walked to the chapel was interpreted as a sign of the King’s innocence. There, in a plain lead coffin, covered by a black velvet pall, he finally escaped the machinations of religion and politics. Bishop Juxon entering St George’s Chapel, Windsor with the coffin of Charles I. The burial service from the Book of Common Prayer was not permitted by Col. Whitchcot, the Governor of the Castle. C W Cope (1811-1890) ‘The Burial of Charles I at Windsor’, mural decoration for the Peers’ Corridor of the Palace of Westminster 1861. This pair of gloves was given to Bishop Juxon by Charles I on the scaffold in 1649. They are now kept at Lambeth Palace. Shortly after his death, and much to the chagrin of Cromwell, copies of Eikon Basilike (the story of the King’s life), went on sale. Its appearance so soon after his death indicates that it had been largely written while he was still alive. It portrayed him as a pious Protestant committed to his duty and his family and did much to further the monarchist cause and the late King’s reputation. 8 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 Frontispiece and title page of the Eikon Basilike, 1649, allegedly written by Charles I. It is probable that it was ghost written by John Gauden, the King's chaplain. It became an instant best-seller and went into 60 editions throughout England and Europe. Why Did the King have to die? Until the installation of the magnificent Rubens ceiling in Banqueting House (Charles was concerned the smoke from the flares would damage it), sumptuous royal masques took place there at regular intervals. The most popular of these were written by Ben Johnson and the costumes and scenery were designed by Inigo Jones – class acts both. The problem was that these masques were not just entertainment; the King saw them as blueprints for Kingship. The basic plot was that chaos and violence would be vanquished by the intervention of the wise and just King, with the Queen embodying pure love and beauty - pretty boring really. His life as King was one long masque with a lot of re-writing by others towards the end. The people of London were probably not greatly impressed by all the pomp and circumstance as they were interested in freedom and justice for all – except the Catholics, of course. And therein lay another serious problem. Charles had married Henrietta Maria, the youngest daughter of King Henry IV of France, by proxy on 11 May 1625, and again in person in Canterbury on 13 June the same year. This allowed no time for Parliament to object and there were certainly many ensuing objections as she was a practising Catholic. Although initially problematic, theirs was a happy marriage and they had 7 children with 3 daughters and 3 sons surviving infancy. Henrietta Maria was not backward in giving Charles her opinion. Unfortunately, she was usually wrong and her interventions just made matters worse. Those who tried to bargain with him soon discovered that he was a fickle negotiater who would basically promise anything to anyone in order to achieve his own ends and would then fail to deliver. His reputation suffered gravely as a consequence. His execution wasn’t inevitable and he had many opportunities to compromise but in the end Cromwell got fed up with him and decided that death was the only way to shut him up. Leaving London and setting up court in Oxford was another mistake. However, Charles had earlier shot his bolt when he entered the House of Commons in 1642 with a warrant to arrest 5 of its 9 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 members who had already made good their escape. Speaker William Lenthall drew a line in the sand that has never been erased when he told the King: ‘May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here.’ Martyrdom and Sainthood When the Church and the Monarchy were restored on 29 May 1660, the name of King Charles I was added to the ecclesiastical calendar in the Book of Common Prayer, for celebration on the anniversary of his death. During Queen Victoria’s reign this was removed. The Feast was later restored to the calendar in the Alternative Service Book of 1980. However, it has not been restored to the Book of Common Prayer and, frankly, I doubt that it ever will be. For example, it refers to the regicides as being ‘cruel and unreasonable’ in their treatment of the King and also to the throne being legitimately claimed back by Charles II, which doesn’t quite fit current circumstances does it? No doubt Charles II felt he had a good case when he asked the bishops to declare his father a martyr saint. There were many claims that the late King’s blood (witnesses paid to dip their handkerchiefs in his blood) brought about miracles. One example was that of the teenage ‘Mayd of Detford’ who suffered from ‘The King’s Evill.’ A woollen draper called John Lane who possessed such a handkerchief gave a piece to her and this was said to have cured her. On 30 January each year a service takes place at Banqueting House, which anyone can attend. It is organised by The Society of King Charles the Martyr (www.skcm.org). Despite being an atheist, I decided to attend and found it very ‘high church’ (Catholic Anglican). The hymns were graphically specific: ‘O holy King, whose severed head The Martyr’s Crown doth ray With gems for every blood-drop shed, Saint Charles! For England pray.’ At the end of the service members of the congregation were invited to venerate his Holy Relics – an invitation I did not take up – and stood in line to kneel and kiss the silver-framed mementoes of his death. Having read the SKCM magazine, it is my feeling that this society is a reactionary faction, which disapproves of women bishops, gay clergy and abortion. Restoration of the Monarchy Cromwell’s son, Richard, inherited the title of Lord Protector briefly on his father’s death in 1658 but he did not inherit his father’s steel will, political nouse or military ability and soon took off abroad. Cromwell had earlier declined the opportunity to be crowned King; well, it would have been rather hypocritical of him wouldn’t it? We English never really had the stomach for regicide and soon General Monck was paving the way for Charles II’s return to London. When the Queen Mother, Henrietta Maria returned to a Royalist London, she took a detour to gaze at the posthumously decapitated head of Cromwell which was displayed on a spike outside Westminster Hall. It 10 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 remained there for 25 years before collapsing altogether and was finally buried secretly at his old college, Sidney Sussex, in Cambridge. A sepia drawing of the head of Oliver Cromwell, from a copy of Pennant's London, circa 1790. Author unknown. Copyright expired. The King was back but his powers had been rigorously pruned and it was now Parliament that held the upper hand. Samuel Pepys sailed back to England on the same ship as Charles II. His diary entry for 25 May 1660 reveals a more human side of the monarchy: ‘I went, and Mr Mansell and one of the King’s footmen, with a dog that the King loved (which shit in the boat, which made us laugh and me think that a King and all that belong to him are but just as others are).’ The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee etc These days Queen Elizabeth II arrives at the state opening of Parliament in a horse-drawn coach to deliver the Queen’s speech. She does so from the throne in the House of Lords to members of both houses. But her role is purely ceremonial and her speech has been written by ‘her’ Government. There have been 12 Prime Ministers during her reign: Winston Churchill, 1951-55 Sir Anthony Eden, 1955-57 Harold Macmillan, 1957-63 Sir Alec Douglas-Home, 1963-64 Harold Wilson, 1964-70 and 1974-76 Edward Heath, 1970-74 James Callaghan, 1976-79 Margaret Thatcher, 1979-90 John Major, 1990-97 Tony Blair, 1997-2007 Gordon Brown, 2007-2010 David Cameron, from 2010 11 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299 In that time she has signed more than 3,500 bills and, as she is about to celebrate her Diamond Jubilee, must be one of the best-informed people on religious, constitutional and political matters in the country. Yet, she is able to say little in public. If history had gone differently we could be preparing to elect our next president. I still don’t want to curtsey to anyone and I reserve the right to chain myself to the railings if I want to but over the years perhaps I’ve mellowed a bit. I’ve grown to admire our Queen who has a difficult job to do and will probably carry on doing it until the day she dies. There are a number of constitutional issues that need to be sorted out before the next King is crowned so the longer she is around, the better. She recently said ‘we should remind ourselves of the significant position of the Church of England in our nation’s life…Its role is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.’ Charles I died because he believed in the Divine Right of Kings. Time has shown him to be very mistaken but that does not detract from his courage in saying ‘no’ and joining the rebellion. ‘It was a place that is trying to destroy the individual by every means possible; trying to break his spirit, so that he accepts that he is No. 6 and will live there happily as No. 6 for ever after. And this is the one rebel that they can't break.’ Patrick McGoohan, The cult TV show ‘The Prisoner’ 1967-1968 12 Anne Reynolds Mapping the City 1369299