Women Sarah Anne

Women’s Essay

History Sarah Anne Cairns

Question: “

Women received the vote based on their contribution to the war effort

”. How accurate is this view that women gained the vote based solely on war work? 20 marks

Attitudes towards women in 1900 were very different from attitudes today. In 1900 women’s personality traits were traditionally that they were emotional, untruthful & immature, and so they were seen unfit and unworthy of the vote by men at that time. Many historians argue that there were many factors which led women to receiving the vote- Martin Pugh says the Suffragists were most important, Paula Bartley argue that pre war changes were important, and Arthur Marwick argues that war accelerated changing attitudes and believes in the reward theory. Women played many vital roles in jobs which had to be filled as men left for war, these jobs were dangerous and many women died, newspapers at the time branded women as

“heroines” for their hard work, as so it can be argued they were given the vote as a reward . However, there are other factors that may have led women to receiving the vote, such as pre-war attitudes as women were beginning to be better educated and have better jobs, the Suffragettes and Suffragists were important as they campaigned for women to have the vote, and finally Foreign Influence as other countries such as Finland had already given women the vote. Therefore, they may not have received the vote solely on their war effort.

Firstly, it can be argued that women received the vote based on their contribution to the war effort. When the men of Britain had to go and fight in WW1, women had to take over the jobs men left behind. Women found themselves undertaking all kinds of work, some unfamiliar, and much of it dangerous or physically demanding, the jobs included munitions with 819,000 female workers in 1917, 45,000 female nurses in

1917 and in transport there was 117,000 workers by 1915. Jobs were often very dangerous, munitions was the most dangerous to work in, as there was an explosion at Silvertown factory in East London killing hundreds, and women were referred to as the “canaries” as the fumes turned their skin a yellow colour.

Work gave women a taste of freedom, better wages, more interesting jobs, promotion and responsibility.

Many women would no longer put up with their old pre-war lifestyle and discrimination, and in turn, women would want the vote to ensure their position in society improved. Some historians believe in the

“reward theory” in which women received the vote in 1918 as a reward for their effort in the war. Arthur

Marwick believes in the reward theory; however Martin Pugh and Paula Bartley believe the reward theory is too simple and flawed. Marwick argues that men working beside women and observing their hard work and responsible attitudes fostered a new respect for them, and that women were now more deserving of the vote.

He states “the war brought a new confidence to women, removed apathy, silenced the female anti suffragists”. Newspapers at the time branded women “heroines” and “The Nation Thanks the Women” posters went up all over Britain, also both the Suffragettes & the Suffragists suspended campaign in order to support the war effort. However historian Paula Bartley quotes “it would be naïve to believe that women received the vote solely for services rendered in WW1”, she also argues it was a strange reward as most war work was done by young women in their early 20`s but they were not given the vote- only their mothers and older sisters over 30 received the vote, who didn’t do nearly as much war work. Historian Marwick states something dramatic must have changed politicians minds between 1912 and 1917, because in the 1912 conciliation bill 208 MP`s voted for women’s suffrage and 222 MP`s were against, yet by 1917 387 voted for women’s suffrage and only 57 against. Another famous historian, Martin Pugh argues that women would have been given the vote eventually as Britain would not want to seem undemocratic and lag behind other countries such as Australia and New Zealand, especially as WW1 was supposedly fought to preserve democracy. Therefore, it can be argued that women received the vote based on their effort in the war.

On the other hand, it can be argued that pre-war attitudes towards women are what led them to receiving the vote, and not solely their contribution to the war effort. Women were viewed as second class citizens in the

late 19 th

century/early 20 th

century, as they were physically, mentally and morally inferior to men, therefore incapable of voting. However, these ideas began to change as they became better educated, had better jobs, and also had an interest in politics. Firstly, education was generally limited to middle class women, and primary education was not made compulsory until 1880, then it was made free in 1894. With compulsory education at primary level, schools were opening for girls, with 349 secondary/grammar schools were opened by 1914. Colleges opened just for women e.g. Girton College in Cambridge 1869, however,

Secondary school & University was not deemed as appropriate for women. Women were allowed to attend lectures and learn the subject at university, but they were barred from exams and denied degrees. As women became better educated, they were no longer viewed as “too stupid” to vote, they were now thought to be more deserving of the vote. Like men earlier, a better education helped women campaign for the vote e.g. writing letters etc. Secondly, women’s jobs and wages were unfair compared to men. Middle class women were not allowed to work once they had been married, and only 25% of working class women worked.

Women worked long hours for low wages, which were generally 1/3 of male wages, and they did not get promoted in their jobs. Women did mainly menial jobs, for example, a female live in servant worked 6 ½ days per week, for only £17 per year. They were still denied better paid & more interesting male jobs, however, new white collar/office jobs were opening up for women e.g. clerical or typing. New white collar jobs gave women a sense of responsibility, and they now had ambition in their life. Some women wanted to improve their opportunities and sought the vote in an attempt to achieve this goal, this also raised their status. Finally, it was believed politics was for men as women should concern themselves only with the home and the family. Women were denied the vote in parliamentary elections, but were allowed to vote and take part in local authority elections. In 1869 women allowed to vote in local council elections, 1870 women were allowed to join school boards, and in 1894 they were allowed to stand as candidates in local elections.

Women had shown they could be successful in participating in local elections and were annoyed that they could not be trusted with the responsibility at national level. Historian Paula Bartley argues it was increasingly ridiculous women could vote locally but not nationally. Women were now also joining political parties such as the Conservative Party’s Primrose League 1883, or the Women’s Liberal Federation 1887, also, increasingly politicians were relying on them for canvassing, but now women were fed up with the two big parties not helping them. Professor Yeo argues that dissatisfaction led to groups like the Suffragists and

Suffragettes being formed. Through political parties women made valuable contacts to help them gain the vote. As argued with Bartley and Pugh, changes in women’s lives to do with jobs, education and voting in local elections made them seem better prepared to vote in national elections pre WW1. Therefore, it can be argued that education, jobs and politics helped women to receive the vote in 1918, and not solely their effort in the war.

However, Women’s suffrage movements were also important in women receiving the vote in 1918; there were two main suffrage movement groups, the Suffragists and the Suffragettes. Firstly, the Suffragists were the first, the biggest and the most successful of women suffrage movements groups. The Suffragists was led by Millicent Fawcett, and they believed in peaceful methods of protest such as writing letters, speaking to

MPs, marches and sending out leaflets. Their numbers grew considerably and was far bigger than the

Suffragettes, in 1907 they had 6,000 members, yet by 1913 they had 50,000 members. Their campaign was suspended in order to help with the war effort in 1914.The Suffragists did not achieve the vote, but many men and women were impressed by their organisation and dignified way they conducted themselves. They attracted many local followers by campaigning vigorously and they won the support of many MPs.

Historian Martin Pugh argues that because of their quiet persuasion many prominent MPs supported them such as Lloyd George. They did not win the vote despite no less than 4 attempts to introduce women’s suffrage bills to parliament. However, there was still a lot of anti suffrage feelings e.g. Queen Victoria claimed women’s rights to be “mad wicked folly”, and also a lot of working class men disliked these pushy, mainly middle class women. Secondly, The Suffragettes, which was led by Emily Pankhurst and her two daughters, believed in militant tactics such as letter bombs and smashing windows. The Suffragettes famous motto was “deeds not words”, and like the Suffragists they too suspended their campaign in order to help

with the war effort in 1914. In 1905-1908 the Suffragettes carried out a campaign of disruption of political meetings, they also heckled politicians, held large parades and chalked slogans on the streets. In 1909-1914 they became increasingly violent, by smashing windows, pepper bombs, chaining themselves to railings etc, as they wanted to be noticed. In 1913 Emily Davidson became the Suffragettes first martyr as she ran out, and was killed by the king’s horse. The Suffragettes are also responsible for the Cat and Mouse Act in 1912, as their hunger strike campaigns resulted in force feeding, the prison would release the women in order to eat and become healthy again, and then they would take them back into prison, over and over again. The

Suffragettes achieved publicity, boost numbers through campaigns- at some rallies as many as 30,000 people attended, and they did put pressure on politicians to try to appease women. However, there was a distinct male backlash against Suffragettes, a National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage was founded in 1911 which included men and women, and also even peaceful groups like the Suffragists were blamed for violence- tarnishing their reputation. Historian Martin Pugh argues that the Suffragettes actually harmed the cause of women’s suffrage movement by turning MPs against them because in the 1911

Conciliation Bill, 225 were for votes for women and 88 against, however the Suffragettes waged a violent campaign against MPs, therefore in 1912, 208 were for votes for women and 222 against. Women had not achieved the vote by 1914 despite the efforts of both peaceful and violent suffrage campaigns. Therefore it can be argued that women’s suffrage movements gained women the vote, as the Suffragists and the

Suffragettes put the issue of votes for women on the political agenda.

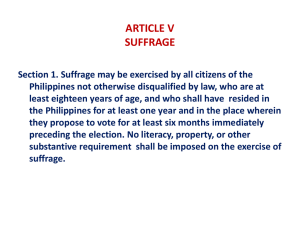

On the other hand, among the factors which led to the enfranchisement of women, the influence of events outside Britain is an important but perhaps a weaker factor. Firstly, the first example of foreign influence was the enfranchisement of women in nations such as Finland, Norway and New Zealand. Britain first granted partial female suffrage in 1918 (to women 30+), and full women’s suffrage in 1928, however, more democratic nations around the world had declared women’s suffrage much earlier, for example New

Zealand granted women’s suffrage in 1893, Finland in 1872 and Norway in 1907. It can be said that the granting of women’s suffrage outside of Britain put some degree of pressure on the British government.

Britain considered itself the “Cradle of Democracy”, and so the idea of other nations surpassing Britain in terms of democratic freedom for women meant that Britain could lose its status. Secondly, the Russian

Revolution in 1917 influenced democratic change in Britain. Before 1917 Russia was ruled by a Monarch,

Tsar Nicholas II, who did not allow democracy to exist in Russia. In 1917 the communist party and its members had successfully taken over the government in an armed revolution. This foreign event showed the

British government the potential for uprisings if democracy was not spread. Given the influence of the radical Suffragettes, there would have existed fear of renewed violence. However, there is no material evidence which demonstrates that the events in Russia and women being granted the vote in counties such as Finland directly influenced the passing of the vote in 1918, although it did contribute. Therefore, it can be argued that foreign influence had a minor impact on the enfranchisement of women in Britain.

In conclusion, the simple answer is that no one reason alone gained women the vote. Women received the vote for a number of reasons, pre-war attitudes towards women were changing long before 1914 as they became better educated and started doing better jobs, the suffrage movement campaigns showed how serious women were about the vote as the Suffragists and Suffragettes campaigned vigorously for the vote, and also the outside influence of other countries such as New Zealand and Finland giving women the vote in

1872 and 1893 compared to Britain giving partial female suffrage in 1918. The women’s war effort was important because work gave women a taste of freedom, better wages, more interesting jobs, promotion and responsibility, and so they seemed more deserving to vote, however, it was just one of many factors.