Executive Summary, Primary Recommendations, and

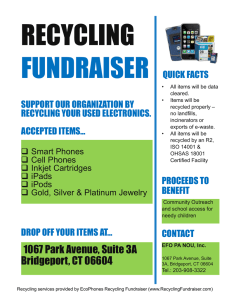

advertisement