Subarctic - WordPress.com

advertisement

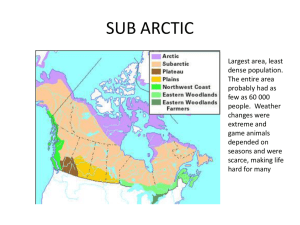

Subarctic Peoples Source: http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/ Location The Subarctic people occupied a majority of Canada from the Yukon to Newfoundland, including parts of seven provinces and two territories. Population The density of the Subarctic human population was among the lowest in the world. The entire area probably had as few as 60 000 people. Weather changes were extreme and game animals depended on seasons and were scarce, making life hard for many. Nations Gwich'in, Han and Tutchone in the Yukon; the Tagish, Tahltan, Kaska, Sekani and Dene (Yellowknife, Dogrib, Hare, Mountain, Slavey, Chipewyan, Beaver, Sarcee) in the northwest; the Tsetsaut; the Inland Tlingit; the Cree, Ojibwa, Saulteaux, Attikamek and Innu in the East. Languages Algonquian was spoken by the Eastern Subarctic groups like the Innu, the Attikamek, the Cree and the Saulteaux. o While their languages were unique, they showed similarities to the Cree language division of Algonquian language. o The Northern Ojibwa speak Ojibwa, another Algonquian language. The people of the Western Subarctic speak Athapascan. Examples: the Tutchone, Gwich'in (formerly Kutchin), the Han, the Dene, the Tagish, the Tahltan, the Tsetsaut, the Kaska and the Sekani. o Some dialects were highly unique and hard to understand. o There were more than 20 different versions of Northern Athapakan languages spoken. FFood Hunting Obtaining food was an important and essential ritual for the Subarctic peoples. Usually on foot or on snowshoes, they would hunt, fish, trap and gather wild plants. Fishing o In the winter, ice fishing was popular. o In the spring, the rivers and the coastal waters were rich in fish and seafood. o Most of the Northern fishes, and their fish eggs, could be eaten. The subarctic people often hunted moose, caribou, hare, musk oxen, bear and elk, as well as waterfowl and fish. The edible wild plants they collected included berries, tripe, dandelions, moss and marigold. Berries were dried in the fall or stored in baskets put in pits in the ground. Pemmican, a mixture of berries, grease and animal meat, was a highenergy food that could be preserved for years. Tutchone families gathered in spring and summer fish camps, at autumn meat camps, and clustered for part of the winter near dried food supplies and at good fish lakes. By later winter, however, they had to scatter Men did most of the big-game hunting, while women snared hare, fished, cut and dried meat, and processed hides. Where Bison and Caribou could be hunted, the drives and the construction and operation of corrals involved most members of the band. Depending on an upland or lowland habitat, some tribes relied more on moose hunting or salmon fishing, while the Caribou was plentiful and a main food source for all. Life depended on the movements of the Barren Ground caribou. The Innu had a special caribou hunt leader (Atik Utshimau), who led the band on the hunt. Considerable effort was taken to cache food and equipment not needed for the season at hand, in specially prepared pits, strong cribbed and conical structures and cairns, or on racks and platforms in trees. Transportation The main transportation of the Subarctic People was walking. Survival depended on being able to travel long distances. Snowshoes were essential for winter travel. Heavy loads were transported on toboggans and, in the far northwest sleds were pulled both by dogs and people. Aboriginally few dogs were available for traction. During the summer, people and their belongings were moved along rivers and lakes by canoe. Since dog traction came only with white contact, belongings were limited to those that could be easily carried or made on the spot, such as the snares used to catch animals of all sizes. Tribal Relations and War The Algonquian speaking groups of Northern Quebec bound together in the mid-17th century, mainly after violent Iroquois wars prompted them to increase their strength to defend and protect themselves if needed. The Innu were descended from people who came to Québec-Labrador thousands of years ago. o They briefly fought the Inuit, Irouquois, Micmac, and Abenaki, but were not a warring nation. o Innu traded with their neighbouring Cree and southern allies. The Chipewyan warred against the southely Cree, but after the 1700s, they allied together and warred against the Inuit and Dene peoples north of them. Religion Nanabush and Wisahkecahk were the hero and trickster figures of the Algonquian culture -The Athapascan culture’s hero was often associated with migratory waterbirds and the sun, both of whom are seen to fly through the heavens. The Hero, in many Subarctic myths, was the first person to become powerful. For them, power and knowledge were combined. The culture hero also had survival skills and outwitted evil medicine persons and fought dangerous animals, and thus made the world a safer place in which humans could live. Gwich'in people believed in animal spirits, spirit beings, bushmen (wild Indians with supernatural attributes). Their hero-trickster was the Raven. Most people had some medicine power, which was enhanced by a body of beliefs, such as customs observed after killing an animal. Dietary and various social observances marked birth, puberty and death. Children learned the importance of good relations with the spirits of animals and other natural phenomena and how they could affect the well-being of a person. Medicine people conducted the shaking tent ceremony, where spirits of people or animals were conjured for curing and prophecy in a tipi. Western Athapascan medicine men and women charged high prices for their services and asserted prerogatives or took liberties among their people. Among the Innu, certain traveling men and women used scapulamancy, a form of divination done by interpreting the pattern of cracks on a caribou shoulder blade heated by fire to determine the trail ahead. The Beaver people of the Peace River region had prophets who were said to have experienced death and flown like swans to a spirit land beyond the sky. They created religious dances based on songs they brought back from their journeys to heaven. Family and Social Structure The family unit was highly valued among the subarctic peoples. Each family was independent, but usually grouped with another family for hunting and ceremony purposes. Gwich’in households housed two same-sex siblings (two sisters, two brothers) who lived together with their immediate families (spouse, children). In the Han’s social unit the elders were included as part of the nuclear family. Han society also encouraged cross-cousins to marry. A young man usually lived at first with his wife's parents then established his own residence and then wealth permitting, he obtained additional wives. Descent for the Athapascans or Dene is connected to the female line; groups were organized into matrilineal bands or clans called moieties, like the Crow and Wolf, meaning bands based on female heredity. Along the Mackenzie River, these ties between bands were connected through both females and males. For the Algonquian groups, some were connected only by males, but there were also bands tied to each other by both the female and male lines. These groupings provided each other with extra hospitality and defense, and together they fulfilled ceremonial obligations for each other (e.g. cremation and/or burial of the dead and reciprocal feasts) and regulated marriage, as band members could not marry each other (promoting exogamy). Kinship names were widely used, but their application was more general (e.g. all the elders were grandfather or grandmother). Children were taught to be self-reliant and learned the habits of game animals and the layout of territory early on. They listened to practical narrative accounts and mythological tales and learned special trapping and hunting songs and riddles. If a child was successful at hunting, he or she had gained the trust of the animals.