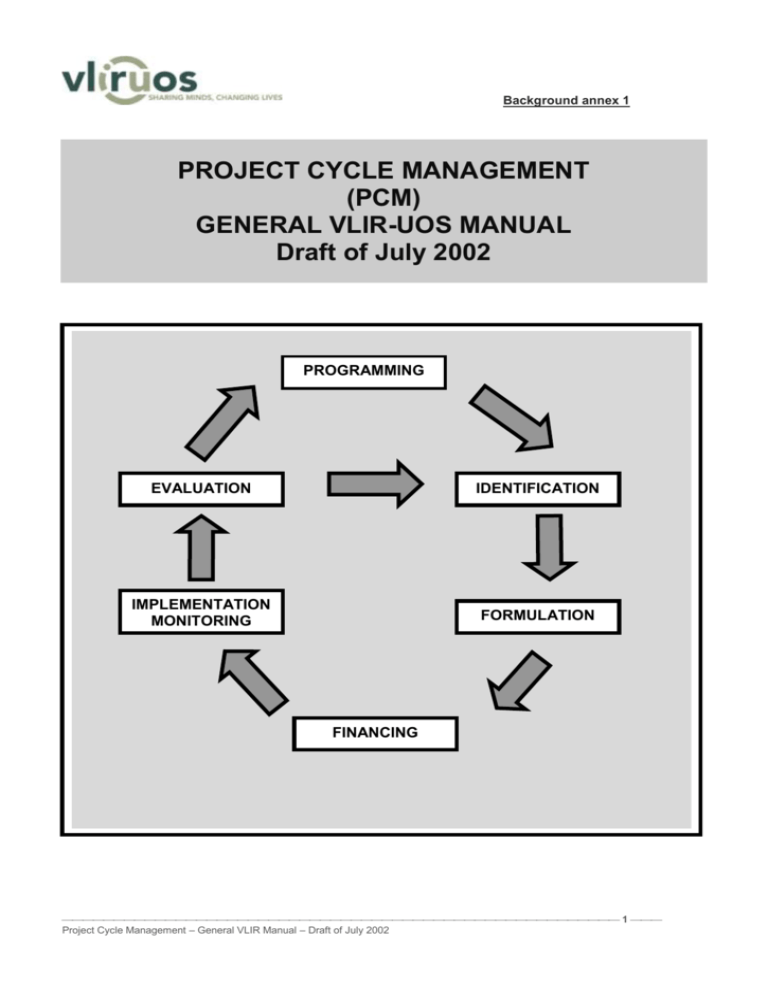

PCM manual - VLIR-UOS

advertisement