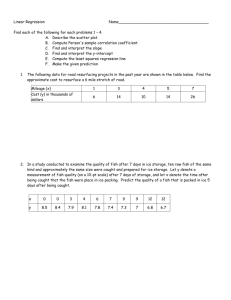

The Heart of the Salmon: A Case Study of Salmon contamination in

advertisement