Cash Flow Statement History & Business Context

advertisement

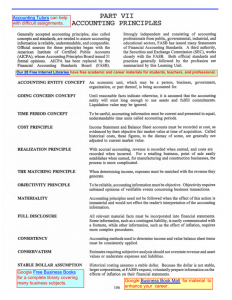

Chapter 6 BUSINESS CONTEXT History of the Cash Flow Statement The balance sheet and income statement have been required statements for years, but the cash flow statement has only been formally required in the United States since 1988. However, cash flow statements, in some form or another, have a long history in the United States. In 1863, the Northern Central Railroad issued a summary of its financial transactions that included an outline of its cash receipts and cash disbursements for the year. In 1971, the APB (predecessor of the FASB) started requiring that a “funds statement” be included as one of the three primary financial statements in annual reports to shareholders. The APB did not specify a single definition or concept of funds or a required format for the statement. The most commonly used definition of “funds” was working capital (current assets minus current liabilities). Thus, a “funds statement” reported changes in cash, accounts receivable, and inventory as if they were the same thing. The funds statement was not without its problems. Buildups in receivables and inventory without a corresponding increase in sales would result in positive funds from operations yet result in no cash. The W. T. Grant Company provided a classic example of the downside of using the working capital definition of funds. The largest retailer in America prior to its bankruptcy filing in 1975 was W. T. Grant, whose continued buildup of inventory and receivables (resulting in positive funds from operations) masked a fiveyear negative cash flow from operations that eventually led to the company’s demise. As a result of numerous cases like W. T. Grant’s, the Financial Executives Institute (FEI) began encouraging its members to adopt a cash emphasis in their funds statements. In 1980, only 10 percent of the Fortune 500 companies used a cash focus; the other 90 percent reported net changes in working capital. By 1985, 70 percent used a cash focus. In late 1987, the FASB finally called for a statement of cash flows to replace the more general funds statement. At that time, the FASB established the statement format that we use today, based on the three-way classification of cash flows into operating, investing, and financing activities. Because the required cash flow statement is relatively young (remember, doubleentry accounting is 500 years old), it sometimes doesn’t get the emphasis it deserves as one of the three primary financial statements. In fact, because the traditional analysis models were developed in an age when cash flow data were not available, analysts will go to great lengths to approximate cash flow numbers, seemingly unaware that since 1988 the actual numbers have been easily available in the cash flow statement. For example, a number often used in evaluating a company’s health is EBITDA—earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. When pressed about why they use this number, an analyst will say, “EBITDA approximates operating cash flow.” Why don’t analysts use the real cash flow numbers? Because information from the cash flow statement is not yet ingrained in the analytical tradition. But it will be. Questions 1. Briefly describe how using the working capital definition of funds masked the cash flow troubles of W. T. Grant. 2. Why is the cash flow statement frequently overlooked by financial analysts? Sources: James H. Thompson and Thomas E. Buttross, “Return to Cash Flow,” The CPA Journal, March 1988, pp. 30–40. James A. Largay III and Clyde P. Stickney, “Cash Flows, Ratio Analysis and the W. T. Grant Company Bankruptcy,” Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1980, pp. 51–54. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, “Statement of Cash Flows,” Stamford: Financial Accounting Standards Board, November 1987.