Date: January 31, 2007 To: Dr. David Hunger From: Steve Caldwell

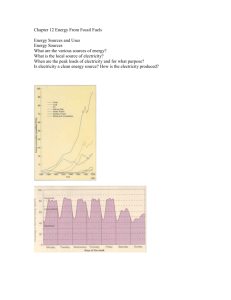

advertisement

DATE: TO: FROM: TOPIC: January 31, 2007 Dr. David Hunger Steve Caldwell Economic Assessment of Energy Tax and Subsidy Policies EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Congress and President Bush have recently proposed a variety of tax, subsidy, and regulatory programs billed as part of a “cleaner, greener” energy policy. An economic assessment of energy tax and subsidy policies finds that: Fossil fuel consumption has costs to society not reflected in market prices Taxes or trade-able permits can force the market to take account of such costs in the most economically efficient way Subsidies of alternative energy research and development promote economic efficiency but subsidies and quotas for the production of alternative energy may not Americans must make political value judgments regarding the distributional effects of different energy policies POLITICAL BACKGROUND High gasoline prices, increasing awareness of the danger of global warming, the Iraq War and other factors have fed growing public concern about energy policy. Congressional Democrats plan to enact changes to energy policy—such as mandating increased use of biofuels. President Bush’s State of the Union address highlighted energy policies, including research grants and quotas for alternative energy. NEGATIVE EXTERNALITIES OF FOSSIL FUELS In 2005, petroleum, coal, and natural gas provided 86% of all US energy. 1 However, the market prices of these energy sources do not reflect their true costs to society. Negative effects of fossil fuel use not reflected in market prices, or negative externalities, fall into three main categories: 1 Environment– the extraction of fossil fuels can damage natural environments, and their combustion releases harmful substances, such as SO2, NOx and ozone. Roughly 80% of US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions come from fossil fuel combustion, and the US emits a fifth of all global GHG emissions.2 The US faces potentially severe damages from global warming including: loss of valuable coastal property to rising sea levels; disruption of agricultural production; and more frequent severe weather events. Economic Growth – the US imports 60% of its petroleum supply. Disruptions to supply could lead to significant price spikes and impact economic growth. National Security – To at least some extent, the US appetite for petroleum funds entities hostile to US national security interests and necessitates political and military entanglements Annual Energy Review 2005, US Energy Information Administration <http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/aer/> “Greenhouse Gases, Climate Change, and Energy,” US Energy Information Administration <http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/1605/ggccebro/chapter1.html> 2 in the Middle East. In addition, fossil fuel energy infrastructure (e.g. pipelines) presents attractive potential targets to terrorists. EFFICIENCY GAINS FROM ENERGY TAXES AND TRADE-ABLE PERMITS Because market prices do not reflect the negative externalities described above, the US consumes more fossil fuel than it ought to from the perspective of economic efficiency—i.e. when one includes the damage from negative externalities, the costs of the current level of fossil fuel consumption exceed the benefits to society. Economists espouse taxes as a means to make the market take account of negative externalities. In terms of policy, the government could set a per-unit tax on fossil fuels to reflect the damage from negative externalities. Such a tax would raise fossil fuel prices faced by consumers and reduce quantity demanded to the socially optimum level. Taxes, however, present a host of practical and political challenges. Taxes on fossil fuels could prove politically unpopular since concern over already high gasoline prices lies behind much of the public attention to energy policy. Instituting the optimal level of taxation requires extensive knowledge of market supply and demand. Setting a tax too low or too high could lead to over- or under-consumption of fossil fuels from an economic efficiency perspective. Finally, adjustment of energy taxes to reflect changing circumstances (e.g. inflation, new technology) would require administrative and possibly legislative action leading to a degree of inflexibility. The US could also address negative externalities via a system of trade-able permits. Under such a system, the government would auction off permits for fossil fuel consumption equal in sum to the optimal level of consumption. Firms who could reduce fossil fuel consumption most inexpensively could sell excess permits to firms who could not as easily reduce fossil fuel usage, thus achieving aggregate reductions at minimum expense. Trade-able permits offer some advantages. First, the government does not need extensive knowledge of supply and demand in order to achieve a targeted level of consumption. Also, a trade-able permit system does not require the administrative adjustments needed to optimize a tax program. While trade-able permits would have largely the same effect as taxes on energy prices faced by consumers, trade-able permits might prove more politically viable since they affect costs less directly than taxes. Economic theory offers important lessons for the design of a tax or trade-able permit system. The government should avoid setting different tax levels or permit allocations across different industries. In the case of reducing GHG emissions, for example, the most economically efficient tax or tradeable permit system would treat a one unit reduction in GHG emissions from transportation the same as a one unit reduction from electricity generation so that market forces would generate the most efficient reduction of GHG emissions. In addition, the government must carefully assess the interaction of energy taxes or trade-able permits with existing taxes in order to avoid harmful distortionary effects. SUBSIDIES AND MANDATES FOR ALTERNATIVE ENERGY To date, the federal government and states have used three primary tactics to promote alternative energy: Production Subsidies –the federal government offers subsidies to producers of alternative energy, such as wind energy and corn-based ethanol Minimum Usage Mandates – federal and state policies require certain minimum levels of alternative energy usage. For example, a current Senate energy bill would set requirements for minimum use of ethanol and biodiesel. Research & Development Subsidies – the federal government offers tax credits and grants to fund research and development in alternative energy. For example, President Bush’s 2008 budget includes $179 million for the Biofuels Initiative. Economic theory does not recommend production subsidies or minimum usage quotas as optimal policies. These policies force the government to choose winners from among the various alternative energy technologies and, in the case of minimum usage mandates, to set quantity. In contrast, under tax or trade-able permit systems that address negative externalities, the “invisible hand” of market forces would lead to the most efficient mix of energy sources. Nonetheless, government subsidies may be needed to overcome economies of scale barriers to the adoption of alternative energies—e.g. retail availability of ethanol or biodiesel. Moreover, the government must ensure that businesses can make confident long-term forecasts of subsidies in order to plan investments appropriately. Economic theory does justify government subsidies for alternative energy research and development. The benefits to society from research into alternative energy exceed the benefits to the individual firms that undertake the research. As such, without subsidies, firms will under-invest in research and development from the perspective of overall economic efficiency. DISTRIBUTIONAL EFFECTS AND EQUITY CONCERNS Any energy tax, subsidy, or trade-able permit policy will have distributional consequences—i.e. differential effects on the welfare of different groups. While economists can identify the most efficient policies and forecast their distributional effects, society must make political value judgments regarding the distributional effects and decide on policies to mitigate them. Energy taxes or trade-able permits would likely raise the prices of certain goods and services and reduce the quantity demanded. This effect could hurt Americans employed in certain industries. For example, US autoworkers might suffer job losses and reduced incomes if a tax on gasoline reduced the quantity of automobiles demanded. In addition, higher energy costs might lead to a larger reduction in welfare for lower income Americans than for more affluent Americans. In addition to costs, one must examine the distribution of benefits from energy policies. For example, policies that reduce air pollution from auto emissions mainly benefit Americans living in urban areas. In the case of global warming, many of the benefits from American GHG reductions would actually accrue to residents of developing nations in Africa and Asia. Domestically, Americans dwelling in vulnerable coastal regions like Florida might disproportionately benefit from GHG reductions.