The Rise of the British Regulatory State

advertisement

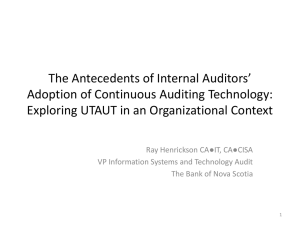

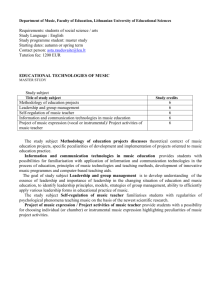

The Rise of the British Regulatory State: Transcending the Privatization Debate David Levi-Faur and Sharon Gilad Senior Research Fellow Regulatory Institutions Network (RegNet) Research School of Social Sciences Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA Tel +61 (0)2 6125 5465 Fax +61 (0)2 6125 4933 Home:+61(0)2 6248 5452 DPhil student Nuffield College and the department of politics and international relations, University of Oxford Tel +44 (0)1856 278561 Home +44 (0)1865 722091 Email: david.levi-faur@anu.edu.au Email: sharon.gilad@nuf.ox.ac.uk ** A Revised Version will appear in Comparative Politics, October 2004 ** We are happy to acknowledge helpful comments and encouragement from Ian Bartle, John Braithwaite, Margit Coen, Jan Froestad, Peter Grabosky, Jacint Jordana, Adam Lefstein, Vibeke Nielsen, Robert (Reuven) Schwartz, Ezra Suleiman, Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan, and the anonymous referees. David Levi-Faur is a Senior Research Fellow at the RegNet programme of the Research School of Social Science, Australian National University. He is also Senior Lecturer at the University of Haifa from which he is currently on leave. He has held research positions in the University of Oxford and the University of Manchester, and visiting positions in the London School of Economics, the University of Amsterdam, the University of Utrecht and the University of California (Berkeley). He published in leading journals such as the Journal of Public Policy, the Journal of European Public Policy, Review of International Relations, Review of International Political Economy, Studies in Comparative International Development, European Journal of Political Research and Comparative Political Studies. His professional interests include comparative politics, comparative political economy and comparative public policy. He currently works on research on the rise of the Regulatory State and Variations in Regulatory Capitalism. Among his publications is an edited volume (together with Jacint Jordana): The Politics of Regulation: Regulatory Reforms and Institutions in the Age of Governance (Edward Elgar, 2004). Sharon Gilad is a DPhil student at Nuffield College and the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford. Her doctoral research inquires into the role of consumer complaints and complaint handling in the regulation of the UK retail investment sector. She previously worked as a governmental lawyer in the fields of taxation and business regulation in Israel. 1 The Rise of the British Regulatory State: Transcending the Privatization Debate Hood, Christopher, Colin Scott, Oliver James, George Jones and Tony Travers, Regulation inside Government: Waste-Watchers, Quality Police and SleazeBusters, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999. Power, Michael, The Audit Society: Rituals of Verification, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999. Moran, Michael, The British Regulatory State: High Modernism and Hyper Innovation, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2003. For almost a century the regulatory state was one of the distinctive features of ‘American exceptionalism’: while other states regulated and while regulations were always a major tool of the state, it was in the United States that regulation through ‘independent regulatory commissions’ became the most visible and celebrated tool of governance. What the United States regulated, other countries often nationalized; where the United States applied legalistic and formal modes of regulations, other countries relied on persuasion, informal exchange, and consensual policy styles.1 The regulatory state is no longer exclusively American.2 Major features of the regulatory state, such as privatization and governance through autonomous regulatory agencies, are a central feature of reforms in the European Union,3 Latin America,4 and East Asia.5 At the same time, new techniques and instruments of regulation are being explored, studied, and implemented in different policy arenas and with regard to innumerable social and political issues. While regulation is by no means new, the last two decades have undoubtedly been an era of institutional regulatory innovations. Since the late 1980s, privatization has been increasingly accompanied by the establishment of state agencies that exert regulatory controls over business entities in fields as diverse as telecommunications, electricity, water, post, media, pharmaceuticals, environment, food safety, occupational safety, insurance, banking, and securities trading. These new entities, often known as independent regulatory authorities,6 have been granted some measure of autonomy 2 from direct political control, allegedly in an effort to increase ‘policy credibility’ visà-vis domestic and international capital.7 Although privatization and institutionally autonomous regulatory agencies are the most visible and celebrated aspects of the regulatory state, our review emphasizes two further characteristics of the new regulatory state which, together with privatization and autonomous regulatory agencies, have transformed the way capitalism is governed: first, the formalization and codification of what was – most probably not only in Britain – an informal way of applying law in general and regulation in particular;8 and second, the proliferation of new mechanisms and techniques of regulation, meta-regulation, and enforced self-regulation.9 These two additional characteristics make for a broader conception of the regulatory state than is usually found in the literature. Most important, the emphasis on meta-regulation and enforced self-regulation suggests the importance of going beyond the notion of ‘regulatory state’ and introducing the notion of ‘regulatory society’ to explain the overall change in governance structures.10 This is altogether puzzling since amidst the rise of neo-liberalism, the prominence of the American deregulation movement, and the teleology of privatization, one might have expected a retreat of the state and a relaxation of rules and regulation. Yet, as the books under review demonstrate, liberalization and managerial reforms that were supposed to ‘hollow out the state’ were intimately coupled with the rise of multilayered regulatory institutions and formalization of codes of behaviour at the corporate, state, and international levels. In contrast to rational choice explanations of increased formalization by reference to the interest of privatized sectors in policy stability, they show that the increase in and formalization of regulation were not limited to sectors that underwent privatization and managerial reforms. The debate seems at last to be moving beyond privatization and interest-driven behaviour. Our aim is to make some sense of these developments and to suggest an interpretive framework that links the rise of regulation with sociological and cultural changes. 3 The three books reviewed here are empirically focused on Britain. However, given both the importance of the British case and the theoretical frameworks that the authors develop, their analysis should be applicable and highly relevant elsewhere. Michael Moran’s The British Regulatory State emphasizes the destruction of an anachronistic governance system that was based on trust and tacit agreements between business and governmental elites and its replacement by a modern system of regulation. Christopher Hood, Colin Scott, Oliver James, George Jones and Tony Travers’s Regulation inside Government focuses on the growth of formal regulatory mechanisms within government. The authors identify several important modes of control and account for the variance in their spread by introducing the notion of the ‘relational distance’ between regulators and regulatees. Finally, Michael Power’s The Audit Society focuses on the explosion of auditing and on the ‘auditization’ of British society. The British—and, Power believes, not only the British—are more concerned with the monitoring of services than with their actual improvement. Rituals of regulatory verifications serve as ‘empty assurances’ for a public who fail to trust professionals’ judgement. This suggests that behind the proliferation and formalization of regulation stands a society that prefers formal rules and regulations to interpersonal trust and individual discretion. I. Moran and the Rise of the British Regulatory State For the first two-thirds of the 20th century, Britain, according to Moran, was the most stable and least innovative country in the capitalist world. Once a byword for stagnation, since the 1980s Britain has been a pioneer of institutional and policy change.11 Moran deals with three major questions regarding the transformation of Britain: Why did this transformation happen? What did it amount to? What were its consequences? Moran describes four prevalent scholarly images of the regulatory state: as an ’American State’,12 as a ‘European Madisonian State’,13 as a ‘Smart State’,14 and as a ‘Risk State’.15 As an alternative, he presents a ‘British’ image of the regulatory state: a state that is grounded uniquely in British history and culture or in British ‘exceptionalism’. Moran fuses economic and cultural perspectives in order to produce a political account of the change. Transformation is said to be driven by the 4 conjunction of the economic crisis in the 1970s, which revealed the long-term decline of the British economy, and ‘a deep institutional crisis’ of British ‘club government’.16 Moran’s focus is on the institutional crisis of ‘club government’, which therefore gets special attention here. Nothing encapsulated club government quite so perfectly, Moran tells us, as the British system of self-regulation: Britain is, in Baggott’s words, ‘a haven for self-regulation’. In this haven self-regulation...has been uniquely informal. Specialized regulators have been rare; instead, regulation has commonly been done as a kind of byproduct of market activity. …the British have been reluctant to codify rules in details, and correspondingly reliant on trust and implicit understandings. Finally, self-regulation in Britain has taken an unusual legal form: private associations, often entirely unknown to the law, have been central to many of the most important systems of self-regulation: and the law itself has historically played no role, or only a residual one, in the life of self-regulatory systems.17 Club government was expressed by oligarchic, informal, and secretive operations in the ‘overlapping spheres of self-regulation and the vast, labyrinthine world of quasigovernment’. 18 It is a deliberate anachronism of a pre-democratic order that served to protect the British elite from democratic pressures. This was made possible by a combination of the British ideology of self-regulation and the public’s deference to business and governmental elites. The old ‘Victorian’ regulatory state, which was a response to industrialization, was intimately embedded in the arrangements of club government. Before the industrial revolution, writes Moran, the economy was certainly regulated, but it is not sensible to speak about a ‘regulatory state’ since bureaucratic institutions were weak and scattered. The growth of the state and the institutionalization of public and private regulatory agencies are all products of the industrial revolution and the Victorian era. Between 1833 and 1850, British politicians created various new institutions to govern social and economic life, including: ‘the Factory Inspectors; the Poor Law Commissioners; the Prison Inspectorate; the Railway Board; the Mining Inspectorate; the Lunacy Commission; the General Board of Health; the Merchant 5 Marine Department; and the Charity Commission’.19 The great Victorian bursts of regulatory institution-building also encompassed some innovation in the selfregulatory system, such as the creation of modern patterns of self-governing professionalism and self-government in the critical financial markets.20 Moran calls these innovations in governance a ‘regulatory state’ because they created (or reorganized) public institutions as regulatory bodies. At the same time, these institutions were shaped by particularly cooperative relationships between regulators and regulatee, and between public and private regulation.21 Moran further implies that this cooperative character resulted in systematic responsiveness to insiders’ and elite interests. As mentioned above, Moran’s focus is on the transformation of that system of governance. The club system was largely shaped by the principle of self-regulation in two domains: the professions and the City of London. It was in the professions and in the City that ‘a dominant British ideology of regulation was hammered out, and was then diffused throughout much of the twentieth century to other parts of the British state and economy’.22 The crisis of club government is also a crisis of self-regulation, and Moran examines, in detail and in a masterly way, changes in the governance of the City, in the professions (lawyers, accountants, doctors, teachers, higher education) and even in a leisure sphere such as sport. As these domains had symbolic importance, their transformation had important effects: ‘A whole way of thinking instinctively about regulation, and a whole way of intellectualizing regulatory activity, was called into question.’23 The transformation of this club government since the 1980s resulted in a system of governance of ‘increasing institutional formality and hierarchy, where the authority of public institutions has been reinforced…by substantial fresh investment in bureaucratic resources to ensure compliance’.24 This new hierarchical system is at the same time made more transparent and open ‘by the provision of systematic information accessible both to insiders and outsiders, and by reporting and control mechanisms that offer the chance of public control’ (albeit a few islands of closed 6 communities immune to external control remain).25 This allows and encourages higher levels of politicization. In contrast to images of withdrawal and hollowing-out of the state, with a transfer of power to international agencies and domestic actors, the change described by Moran is one of a vigorous regulatory state whose central ambitions have not diminished. On the contrary, it uses command and control regulation to colonize new areas, develop new agencies and reform old ones.26 The tools it applies to achieve these ambitions are entirely congruent with ‘high modernism’: that is, standardization, central control, and synoptic legibility to the centre.27 Yet, as elaborated later, these innovations and reforms amount, according to Moran, to an incomplete reconciliation with modern conditions of globalization.28 II. A Regulatory State within the State: on Waste-Watchers, Quality Policy and Sleaze-Busters While the rise of the regulatory state in Britain, as studied by Moran, is something that happens between state and society, Hood and his colleagues examine it within the British government. The context of their study is the managerial reforms of the 1980s and 1990s (the so called New Public Management), which promoted decentralization and managerial autonomy. The authors study the effects of these reforms on the modes of control and the relationships between regulators and regulatees within government. This they do by systematic comparison of changes in the modes of control over central government, local government, prisons, schools and EU overseeing of the UK public sector. What may have been described by others or in the past as ‘administration’ is brought into the framework of regulatory theory. Just as business firms are exposed to a set of different regulators – auditors, inspectors, licensing bodies and competition authorities –– so are public organizations. A collection of waste-watchers, quality police, sleaze- 7 busters, and the like exert their powers on local authorities, schools, health suppliers, regulatory agencies, prisons, and executive agencies. Some of these overseeing organizations are common to the public and private sectors, but many are specific to public bodies in the form of distinctive systems of audit, grievance handling, standard setting, inspection, and evaluation. The overall scope and scale of regulation within the British government is perplexing and it is certainly a growth industry. The British government, they argue, expends more effort on regulating itself than it does on regulating the much-discussed privatized utilities They count 135 separate regulators in total, ‘directly employing around 14,000 staff, and costing £770m to run in 1995 – just over 30p in every £100 the UK government spent…’.29 This is a conservative estimate of change that was ignored by others. And its impact is even larger if one considers the massive compliance costs for the regulated agencies. For example, inspection of secondary schools has been estimated to cost each school around £20,000 in expenses directly connected to the inspection.30 Moreover, ‘regulators of government for the most part made no attempt to assess the costs to their clients of complying with their demands’.31 In an era when governments aspired to be leaner and meaner in the name of efficiency, regulators within government approximately doubled their budget. From the 1980s the British government substantially reduced the number of its direct employees – with more than one civil servant in four disappearing from the payroll between 1976 and 1996. Yet total staffing in public sector regulatory bodies went dramatically in the other direction, with an estimated growth of 90% between 1976 and 1995.32 It might well be that this growth reflects their role as an instrument chosen for making the rest of the public service leaner and meaner. Indeed, if the patterns of regulatory growth and civil service downsizing had continued at the 1975-1995 rate indefinitely, the authors estimate that late in this decade the civil service would have had more than two regulators for every ‘doer’ and over ten regulatory organizations for every major government department.33 The authors examine the above dynamic against four ideal types of controls: oversight (command and control techniques), mutuality (informal peer control), competition 8 (use of internal markets, comparative tables, lateral entry, etc.), and contrived randomness (control through unpredictable processes or pay-offs). They demonstrate that these ‘ideal’ forms of control are in reality mixed together in several ‘hybrids of controls’ and suggest that, within government, control shifted from predominant reliance on informal peer control to reliance on a particular popular hybrid that combined formal oversight and competition. Still, the degree of codification and formalization varies across central policy departments (where control by mutuality is still the main source of control), executive agencies, and the margins of government (where formalization of rules, group division between regulators and regulatees, and the use of comparative indicators are more accentuated). Moreover, while in the vicinity of Whitehall the increase in formal regulation co-exists with (and compensates for) higher managerial autonomy, at the margin of the state it is combined with detailed central micro-management of local service delivery. Hood and his colleagues, following a study by Grabosky and Braithwaite,34 relate this variance in regulatory modes to different levels of relational distance, that is, to the scope, frequency, and length of interaction between regulators and regulatees.35 Higher formality of regulation at the margins of the state is associated with higher relational distance, that is, the difference in professional and career backgrounds of regulators and regulatees and infrequent regulator-regulatee contact.36 The authors’ explanatory framework shifts the discussion from actors’ rationality and interests to the socio-cultural aspects of regulators’ and regulatees’ relationships. The contribution of the book goes beyond applying socio-cultural lenses to an examination of the relationship between regulators and regulatees. Its interpretation and exploration of within-government control in terms of regulation opens a new agenda for public administration research. In addition, it invites us to broaden our thinking about regulation beyond the narrow contexts of privatization and government-business relationships. Last, by showing variance in regulation of different sectors within the same country (Britain), the book questions the simplistic 9 tendencies to think of regulation in terms of coherent national styles and of overarching and global trends. III. The Audit Explosion and the Regulatory State Michael Power’s The Audit Society is an intriguing exploration of the dynamics of public control over business through one particular instrument of regulation – auditing. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, he observes, the practice and terminology of auditing began to be used in Britain with growing frequency and in a wide variety of contexts. Financial auditing, the traditional regulation of private companies’ accounting by external financial auditors, came to acquire new forms and vigour. Among the emerging new forms of auditing were forensic audit, data audit, intellectual property audit, medical audit, teaching audit, and technology audit. Auditing won a degree of stability and legitimacy that institutionalized it as a major tool of governance well beyond the control of business: ’increasing numbers of individuals and organizations found themselves subject to a new or more intensive accounting and audit requirement… and a formalized and detailed checking up on what they do.’37 The augmentation of auditing practices creates the ‘audit society’, ’the extreme case of checking gone wild, of ritualized practices of verification whose technical efficacy is less significant than their role in the production of organizational legitimacy…’.38. Building on his observations about the growing importance of auditing, Power sets out to explore the following questions: ‘How and why did auditing become so attractive to so many diverse groups? ... How can auditing be such a robust policy tool when it often seems to fail so spectacularly? And how do we begin to understand a society which seems to invest so heavily in such an instrument of regulation?’39 What drives the ‘audit explosion’? He sees it as the result of the 1980s and 1990s reforms in governance, which shared the incompatible ideals of small and non-intervening government on the one hand and accountability and transparency of public services on the other. Small government entailed limiting state regulation, while the quest for accountability and transparency required augmentation of control mechanisms. The result was reliance on a combination of state regulation and various forms of self- 10 regulation and auditing (which came to be understood as the suitable and legitimate mechanism for ensuring accountability). As the state became increasingly and explicitly committed to an indirect supervisory role, audit and accounting practices assumed a decisive function.40 Accordingly, auditing became a necessary mediator between systems of self-control and state systems of regulation.41 Power argues that two developments are occurring simultaneously: reallocation of regulatory functions down to auditors and corporations, and a drift from an inspection to an audit style of regulation. Inspection focuses on the processes and outcomes of regulatees’ activity, while audit is limited to assessing the robustness of internal corporate control systems over these processes and outcomes. As a result, both state regulation and auditing amount to assurance that corporate control systems adhere to procedural auditing provisions. The danger, which Power highlights, is that this adherence may imply nothing about the actual quality of the services thereby provided to the public. The explosion of auditing is not just a response to the problems of corporate control in an era of state contraction. Power perceives it as embodying also a cultural trait of a society that favours technocratic procedures (as a tool of providing assurance) over individual professional judgement.42 Surveillance via auditing provides false assurance and comfort, with every regulatory failure resulting in more formalization and more auditing rather than deep reflection on the sources of failure. All in all, Power’s account is thought-provoking and, although he provides no systematic empirical evidence to validate the relationship between change in public attitude and formalization of audit, this weakness is ameliorated by the book’s theoretical strength. IV. Whither the British Regulatory State? All three books concur that British governance system is changing. But what exactly is changing? And how are these changes reflected in the rise of regulatory mechanisms? Four characteristics of the change are particularly important. First is a new division of labour between state and society with regard to the role and functions of the state and consequently increasing reliance of the state on rule-making rather 11 than spending. Second is a new division of labour inside the executive branch of the state. This is manifested largely in the increasing delegation of authority to institutionally autonomous regulatory agencies and to separate ‘next steps’ delivery agencies. Third is change in the relations between regulators and regulated, expressed in increasing formalization of rules and codification of responsibilities in both public and private spheres. Fourth is the proliferation of technologies of regulation, most notably self-regulation, meta-regulation, and enforced self-regulation.43 We suggest that these four characteristics capture best the essence of the rise of the British regulatory state.44 Let us start with the new division between state and society (or between governmental and non-governmental actors). This is the most obvious and familiar aspect of the neo-liberal agenda and is closely related to policies of ownership privatization. It reflects the popular metaphor of a steering (leading, thinking, directing, guiding) role for the state and a rowing (enterprising, service-provision) role for society and business.45 Consequently, the regulatory state is characterized by a shift in the mode of control from taxing and spending to rule-making, with the caveat that this should be interpreted as a shift in emphasis rather than the relinquishing of taxing and spending in favour of rule-making.46 Second, the regulatory state represents a new ideal of division of labour within the state. Policy-making, regulation, and service-delivery activities that were unified constitutionally under ministerial control are now shared and divided between different organizations. Delegation of authority to regulators (inside and outside the state) seems to be one of the manifestations of the change in governance in general and of the rise of the regulatory state in particular: ‘An increased willingness to delegate important policy-making powers to technocratic bodies enjoying considerable political independence’ is a distinctive feature of the changing nature of policy-making since the 1980s.47 The new agencies seem to be not only the most visible aspect of the regulatory state but also one of the popular subjects of research. Third, changes in relations between regulators and regulatees are manifested in an increase in the formalization and codification of rules and responsibilities in public 12 and private spheres. Moran and Hood et al. paint a similar picture of British regulation shifting from informal peer control to predominantly command and control-type regulation. Power offers a similar narrative of auditing procedures becoming increasingly formalized, offering less ad hoc discretion to individual auditors in their relationship with auditees. It is unclear, though, how far this formalization goes beyond the policy level and what its effects are in practice. Moran generally assumes that changes at the legal and institutional levels reflect changes in enforcement. Yet it is plausible that at the implementation level there are, as before, negotiations and flexible cooperation between regulators and regulatees, in spite of higher rule formalization. Regulators depend to some degree on regulatees’ information, knowledge, and personnel, and this dependency invites informal cooperation in the shadow of formalization. In addition, regulators may be forward- rather than backward-looking and thus may prefer persuasion to the use of sanctions. Indeed, even in the context of local government regulation by central government, one of the most conflictual areas explored by Hood and his colleagues, the authors note a persistence of cooperative relations. ‘On paper, oversight regimes could seem formal and cold, but the way they were applied could involve mutually supportive relationships.’48 Such cooperative relationships are congruent with Grabosky and Braithwaite’s study of 96 regulatory agencies in Australia.49 They are also compatible with Blau’s ethnography of a New Deal enforcement agency’s relationship with its regulated firms, with Selznick’s study of the US TVA’s relationship with its environment and with the ubiquitous American literature on regulatory capture.50 Hence, this suggests that the formalization of British regulation may be directed towards the assurance of outsiders – the public – while flexible cooperation between regulators and regulatees may remain indispensable given their interdependence. The fourth characteristic of the rise of the regulatory state is the proliferation of technologies of regulation, self-regulation, meta-regulation, and enforced selfregulation. The effectiveness of regulatory regimes relies on the effectiveness not just of the inspectors: it relies also on a wider range of actors, who are empowered by new regulatory mechanisms and technologies largely in the shadow of the state. Some of 13 these mechanisms are captured in the reviewed books, but for others we turn to the socio-legal literature on regulation. Three types of non-state mechanisms of regulation may be discussed. The first is ‘gatekeepers’, that is, private parties who are in a position to counter misconduct by withholding their cooperation from a wrongdoer.51 These private parties can be employees of the corporations or professional advisers who have the autonomy and the power to object to rule-breaking. The autonomy of such actors can be strengthened by legislation that will allow them some leverage to avoid loss of contract or employment (if they are employees of a corporation that does not act according to the rules). 52 A second mechanism of improving public control without over-reliance on state regulators is that of enforced self-regulation.53 Here, public controls are enhanced by public requirements from corporations and other organizations to act according to transparent and self-defined rules and standards and to self-monitor the implementation of these standards. 54 Citizens’ and consumers’ charters and other codes of best practice are classic examples. Moran’s account of the decline of ‘club government’ and self-regulation reveals that he similarly distinguishes between forms of self-regulation. What is declining is voluntary self-regulation, in which the state has a marginal role. Instead, forms of state-sponsored or enforced self-regulation are being developed. A third mechanism for public control which is closely related to enforced self-regulation is meta-regulation, or what Power terms the ‘audit style of regulation’. Here public control is enhanced by the institutionalization of ‘controls of controls’. This is the monitoring of the self-monitoring techniques of corporations as to their employees’ compliance with socially valued standards of behaviour. According to Bronwen Morgan, the notion of meta-regulation captures a desire or tendency ‘to think reflexively about regulation, such that rather than regulating social and individual action directly, the process of regulation itself becomes regulated’.55 The notions of enforced self-regulation and of meta-regulation reflect a growing recognition in socio-legal literature that systems of law enforcement that are based on responsive regulation are more effective and socially desired.56 But note Power’s reservations when he suggests that ‘control of control’ (i.e. ‘audit style of regulation’) 14 may result in regulatory disengagement from outcomes in favour of hollow approval of system controls. It should also be noted that systems of internal controls that were always part of the work of organizations are increasingly coming under public scrutiny, most notably the scrutiny of the state. While the state has no monopoly over regulatory power, it is still a major pillar of the new order and in the creation and proliferation of non-state mechanisms of control.57 From our point of view, therefore, the debate on the decline of the state seems to miss the important ways that public interest is reasserted in its shadow. The mechanisms of regulation and compliance that were noted here provide a multi-layered system of regulatory controls that for better or worse is one of the major characteristics of the regulatory state.58 While each of these mechanisms may have numerous flaws, the effectiveness and the performance of regulatory regimes rely on all of them together. While these various mechanisms of self-regulation are often discarded as ineffective, we suggest that ‘self-regulation’ is a double-edged sword. Self-regulation may act as a buffer against public control, but it may also operate as a tool of public control via internalization of public norms or responsiveness to concrete public pressures and demands. Accordingly, we should move beyond the dichotomy of self-regulation and public regulation towards a study of the interaction of various forms of complementary controls. V. Why the Regulatory State? The British regulatory state seems to be characterized by higher investment in oversight regulation (compounded with performance measurement), enforced selfregulation, formalization (of rules and regulatory institutions), and juridification. Why did regulation and its formalization generally increase during the 1980s and 1990s? None of the reviewed books answers this question in full, although each offers some possible clues.59 One way to explain the change is to argue that central government politicians and bureaucrats compensated for the risk associated with loss of control resulting from managerial autonomy granted under managerial reforms, delegation and privatization, by reasserting control via regulation. Similarly, it is arguable that 15 regulation of liberalized industries increased as a central response to the incentives created for corporations by heightened competition to cut costs, so potentially undermining quality. However, these explanations fail to deal with the increase and formalization of regulation that Hood and his colleagues observed in sectors, such as education, local government, and non-privatized prisons, where delegation and managerialism were minimal. In these sectors what they encountered was not a ‘mirror image’ of augmenting regulation compensating for managerial autonomy, but a pure increase in regulation alongside lower levels of managerial discretion. Similarly, the audit society as described by Power goes well beyond a response to the specific demands of new public management reforms. Another possible answer, to be only tentatively explored here, focuses on sociocultural explanations: the relationship between trust, relational distance and the rise of regulation. Defining trust is not an easy task and beyond the scope of this paper. 60 In modern, complex societies, trust and oversight are to some extent exchangeable.61 Where trust is present, oversight regulation is perceived as redundant, and vice versa. The importance of trust increases, therefore, where discretion and freedom prevail: ’if other people’s actions were heavily constrained, the role of trust in governing our decisions would be proportionately smaller, for the more limited people’s freedom, the more restricted the field of actions in which we are required to guess ex ante the probability of their performing them…trust becomes salient for our decisions and actions the larger the feasible set of alternatives open to others.’62 Two hypotheses may be derived from the reviewed books about the relationship between relational distance, trust and regulation in Britain and elsewhere. First, the increase in oversight regulation and in enforced self-regulation developed as a substitute for the erosion of trust between private consumers and service providers (requiring third-party regulation) or increased relational distance between regulators and regulatees (resulting in distrust of various forms of self-regulation). Second, formalization of regulation took place because there was an erosion of trust in the ability of informal regulatory institutions to provide public assurance. Hence, 16 formalization was a tool for the restoration of public trust in the effectiveness of these institutions. Moran relates the increase in regulation and its formality to an objective social change – the destruction of club government (which he equates with the ‘old boys club’) – and to a cultural rift in the British public’s subjective deference to the elite. However, the association between the sociological change and the cultural change is unclear from his analysis. Hood and his colleagues link variance in regulatory modes and formalization to different levels of relational distance, associating higher levels of relational distance with more formalized within-government regulation. What is the relationship between relational distance and trust? We suggest that the two may be closely related. Relational distance measures the objective reality of social relationships rather than a subjective expectation. It is reasonable to expect, as Gambetta does, that subjective trust is a by-product of objective familiarity (of low relational distance) and a common value system that allows reliance on compliance rather than deterrence systems of law enforcement. Hood and his colleagues seem to assume such a connection when explaining that ’relational distance factors would lead formality…to be highest at the boundaries of public administration cultures where trust might be expected to be lowest…’ (our emphasis).63 Regulation inside Government offers some empirical substantiation for the case that higher relational distance results in more formalized regulation. We suggest that decline in interpersonal trust may be the mechanism through which higher relational distance between regulators and regulatees results in formalization. But, as further discussed below, decline in trust is not just an outcome of greater relational distance; it may also be its cause. In the executive agencies around Whitehall, it seems plausible to suggest a causal relationship between increase in relational distance resulting in decline in trust and increase in regulation. The evidence presented suggests that agencification and lateral entry to the civil service weakened mutual social norms between regulators and regulatees and thus led to an increase in relational distance. The explanations that relate increasing regulation and formalization to loss of control and to a socio-cultural change seem to work in tandem. 17 But, in the boundaries of the state – such as local government and school regulation – the state did not lose control, but centralized a control it never possessed. The increase in relational distance between regulators and regulatees was intentionally constructed as a tool of centralization. Regulatory bodies were designed so as to base their recruitment from outside the regulated sector in order to distance them from their regulatees. This, for instance, was the idea behind Ofsted’s contracted-out school inspection and the inclusion of lay people in bodies inspecting prisons. In some cases, the reason for designing a higher relational distance between regulators and regulatees seems to accord with the second hypothesis above – that is, as means of restoring public trust in regulatory institutions.64 For instance, ‘a leading inspector of fire services said lay inspectors had been introduced for “political reasons”: “they had to appear not subject to service capture”…’ (our emphasis).65 Similarly, Power explains audit formalization as a means of maintaining public trust in audit as a system of regulation, in spite of recurrent scandals. Therefore, if this interpretation is correct, declining (or apparently declining) public trust in institutions resulted in political construction of higher relational distance between regulators and regulatees, resulting in adversarial relationships.66 This explains how regulation and audit developed and became formalized over time as a response to recurrent regulatory failures and adverse public opinion. What is left unexplained in our formulation is Moran’s observation that the major changes in regulation occurred after the economic crisis of the 1970s. If this is true, why is it that scandals and regulatory failures prior to the 1970s resulted in lesser regulatory reforms? This puzzle, which remains unsolved by the above analysis, takes us to Power’s audit society. Power ascribes the audit explosion in the 1980s and 1990s to a change in society’s risk toleration and the implications of this change for a general inclination to rely on rule-bound mechanisms of surveillance rather than on individual discretion. His argument conveys an understanding of change according to which auditing signifies a distinctive phase in the development of capitalist societies as they grapple with the production of risks, the erosion of social trust, fiscal crises, and the need for public 18 control.67 Societies that are less tolerant of risk and are unable to assess it or to construct a rational response seek comfort in the process of auditing, which they find more trustworthy than business and government. The same may be said of formalized regulation more generally. Paradoxically, trust withdrawn from some people is placed in others, or rather in auditing and regulation as technocratic systems of knowledge. Trust thus lets itself in through the back door. As argued above, this is indeed a potentially fertile theory that requires systematic empirical analysis. VI. The Social and Political Pathologies of the Regulatory State While earlier accounts of the rise of the regulatory state focused on problems of delegation and the advantages and disadvantages of regulation compared with public ownership, the books under review extend the criteria for assessment well beyond the privatization debate. Moran asks to what extent the new regulatory state in Britain is a manifestation of progress, policy learning, and ‘reconciliation with modernity’. The British regulatory state is for him a creature of modernity in the sense that ’the state turned to the reconstruction of institutions and economic practices, with the aim of raising competitiveness against global competition’.68 The second dimension of this modernization project is the advance in the destruction of club government and its substitution by a hierarchical and more transparent apparatus, which is open to the influence of diverse groups. For instance, in the context of regulation of privatized industries, Moran claims: ’By any of the standards by which we might expect to judge economic government in liberal democracy – accountability, transparency, plurality of representation – [the current regime is] …immensely superior…’.69 As to this second dimension, it is still an open question whether nationalized industries and other governance systems from the post-war period were more elite-oriented and closed than the meritocratic system of the 1980s and the 1990s. Alongside his optimistic evaluation of the change, Moran claims that the outcomes resulted also in constant instability. Innovation in the regulatory field is portrayed as ‘hyper-innovation’, a ‘frenetic selection of new institutional modes, and their equally 19 frenetic replacement by alternatives’.70 This might explain why advances in the tools and theory of governance that should improve the capacity of the state to govern result too often in scandals and policy catastrophes. Bringing globalization into the picture (in a rather limited account), he suggests it may frustrate at least some of the modernization ambitions of the British government. In a global world ’the state remains a critically important actor, but its importance lies less in traditional command than in the contingent ability to operate in globally constituted networks’.71 He is therefore doubtful that the state has any longer the capacities – either the policy competence or the symbolic capital – to effectively realize its ambitions.72 Hood and his colleagues focus on three major problems of the patchy system of regulation within government. First, they point to the lack of an overall rationale of regulation inside government. As was elaborated above, the number of regulators and the costs imposed by regulation inside government are increasing. What these proliferating regulatory bodies critically lack are common goals and coordination, each striving for different and often inconsistent aims. The authors found that there is no single focal point for the 130-plus regulatory organizations, no overall ‘policy community’ for regulation in government, and no central point in Whitehall capable of, or responsible for, overseeing, or gauging its size and growth.73 This results in failure to exchange knowledge and expertise with other agencies, and most probably in inefficient and costly controls too. Second is the problem of double standards in the strictness of regulatory controls depending on the relational distance between regulators and regulatees. Third, Regulation inside Government is highly critical of the accountability of the ‘regulators of regulators’. ‘[D]o as I say, not as I do’ seems to be the (double) standard in the work of regulators within the state.74 The problem of who regulates the regulators thereby arises as a problem of second-order regulation. Unlike the foregoing discussion, which focused on the regulatory state, Power’s attention is focused on the ‘regulatory society’ and its pathologies. Instead of providing a critique and an arena for reflection, audit produces comfort and reassurance, and consequently reaffirms the existing order. As a result, not only does auditing fail to provide substantial corporate accountability, it also overlays public 20 deliberation with obscure professional discourse. The audit society, and by implication the regulatory society, represents a case of ‘checking gone wild’.75 Checking is useful and unavoidable, argues Power, but a balance should be sought between surveillance and trust. From Power’s point of view, the audit society has gone too far in its reliance on surveillance rather than trust : ‘Could one imagine a society, or even a group of people, where nothing was trusted and where explicit checking and monitoring were more or less constant?... Having said this, could one imagine a society without any checking at all, a society of pure trust where all accounts are taken at face value? This is equally difficult to conceptualize. Where expectations are disappointed is it not simply naïve to carry on as before?... What we need to decide as individuals, organizations, and societies, is how to combine checking and trusting.’76 This malaise goes beyond the economic costs of too much checking and costly regulation as it presents a form of ‘learned ignorance’. Interestingly, the auditing explosion is not to be interpreted as evidence of its success as an instrument of public control. It is simply beyond the technical capacity of the auditing process to provide what it programmatically promises, argues Power. Certain limits, most obviously the economic costs of auditing, constrain the auditors’ ability to protect stakeholders from abuse. Unfortunately, the limits of auditing are hardly transparent to the stakeholders and the public at large. Power goes on to question the foundations of auditing as a system of knowledge. He argues that there is no external measure to assess whether an audit provides a suitable level of assurance other than an opinion based on the internal logic of audit as a discipline. Audit’s limitations are regularly revealed every few years following scandals. Yet the responses of auditors and politicians to adverse public opinion are manifested not only in corrections of actual holes in the system but also in increasing limitations on the discretion of auditors by means of formalized procedures. In this way, despite persistent regulatory failures, public trust in audit as a system of knowledge is preserved and failure is particularized as ‘bad auditing’. This further consolidates a situation in which state regulators and auditors have become a chain of hollow approval of lower-level auditors’ opinion that the system is maintaining adequate levels of system control safeguards, as defined by the formalized audit procedures: 21 Audit cloaks its fundamental epistemological obscurity in a wide range of procedures and routines. From time to time audit practitioners have worried about the erosion of judgment and the imposition of too much structure on the audit process, but the history of financial auditing and the recent history of other forms of audit suggests that codification and formalization is continuing…77 All in all, while all authors seem to see some valuable advances following the changes in the British governance system, particularly in the way regulatory controls are exerted, they point to a set of problems or pathologies of the regulatory state. Moran emphasizes the limits of command and control regulation in the context of globalization and Europeanization. Hood and his colleagues focus on problems in the coordination of the system of regulatory control inside government and the prevalence of double standards depending on the relational distance between regulators and regulatees. Finally, Power emphasizes the problem of distrust that ‘spreads suspicion’, resulting in a focus on process instead of substance, and consequently in limitations on valuable professional discretion. VII. The Regulatory State beyond Britain: A Challenge for Comparativists The reviewed books agree in their understanding of the rise of the regulatory state as a phenomenon that goes beyond privatization, beyond the creation of new state agencies, and beyond the subsequent increase in the extent of delegation. They also concur in their insight that regulation is being increasingly codified and formalized, and that pure forms of control via informal rules are on the retreat. Our discussion emphasized the interrelated and overlapping regimes: international organizations’ regulation of national governments, inside-government regulation, government regulation of business, enforced-self regulation and meta-regulation. Regulation is thereby conceived as a system of public control, which is carried out by private as well as public actors on the national and international levels. These regulatory arenas are 22 connected through mechanisms of meta-regulation and enforced self-regulation, and reflect social, economic and political change. Regulation in this wider formulation may become one of the central objects of inquiry of social science.78 To what extent can these observations about the British regulatory state be generalized? To what extent can the four characteristics of the regulatory state be found in other countries? It is clear to us that privatization and regulatory reforms are general phenomena. There is widespread diffusion of privatization across the world (with a notable exception of the Arab world).79 Beyond privatization we find sweeping diffusion of autonomous regulatory agencies. A study of the rise of regulatory institutions in the telecoms and electricity industries found that by the end of 2002 at least 120 countries had established new regulatory authorities in the telecoms industry and 70 in electricity. The popularity of these institutions might be demonstrated more clearly when these numbers are compared with the relatively scarcity of these institutions up to 1989. By that year only 11 countries had regulatory authorities in telecoms and only five in electricity.80 A summary picture of data on the diffusion of these institutions across 36 countries and 7 different sectors is presented in the Graph.81 This institutional innovation, which is so central to the argument about the rise of the regulatory state, seems to be more and more prevalent. From 28 agencies in 1986 (fewer than one agency per country), by 2002 the number had increased almost sixfold to 164. On average these 36 countries have 4.5 agencies in the 7 sectors studied. Yet we know little about the increase in the degree of formalization and about the proliferation of regulatory technologies. Some country and arena studies suggest that this is hardly unique to Britain. However, unfortunately neither do we have the quantitative studies that examine various manifestations of regulatory techniques beyond one country, sector or arena, nor are we familiar with country studies that are equivalent in scope and insight to what the three reviewed books say about Britain.82 In other words, the extent to which the British regulatory state is replicated and diffused elsewhere is still an open question, in respect of at least some of the 23 characteristics that we have mentioned. More country studies on the regulatory state, preferably of a comparative nature, are needed (although, given our review and given the increasing venues for contagious diffusion, we would be surprised if Britain is exceptional). Indeed, it seems to us as suggested by Moran that it is indeed a pioneer of change, though the extent to which these changes serve the same purpose in other countries is doubtful. We make three suggestions for future research on the regulatory state. The first is to move beyond disciplinary walls. What we know about the various facets of the rise of regulation is confined by disciplinary boundaries that need to be lowered. We call for multi-disciplinary approaches to the study of regulation, not because other disciplines offer better insights about politics but because our understanding of the political process might improve if we grasp the nature of regulatory change in wider contexts than usually suggested. Specifically, while many attempts to breach disciplinary walls have been aimed at the economics of regulation and Law and Economics, we suggest that the socio-legal literature on regulation offers insights and lessons that are underutilized by political scientists. Second, we also suggest moving beyond the state. This is not because the state is not an important actor; indeed, we hold that the state is still an important pillar of the new governance system. Finally, we suggest that exploring the rise of a regulatory society, alongside a regulatory state, might be useful as a future research agenda. Rather than studying each on its own, we suggest looking for ways in which the regulatory society and the regulatory state transform and constitute one another. 24 200 150 100 50 0 19 87 19 88 19 89 19 90 19 91 19 92 19 93 19 94 19 95 19 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 20 02 No of Regulatory Authorties Graph1: the Diffusion of "Independent Regulatory Agencies" (36 coutnries, 7 sectors) Total number of agencies peryear 25 Notes 1 For Britain, see, Keith Hawkins, Environment and Enforcement: Regulation and the Social Definition of Pollution (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1984); David Vogel, National Styles of Regulation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986). For a study that maps cross-national policy styles, see Frans van Waarden, ‘Persistence of National Policy Styles: A Study of Their Institutional Foundations’, in: Unger, Brigitte and Waarden, Frans van, Eds., Convergence or Diversity? (Aldershot, USA: Avebury, 1995), pp. 333-372. 2 A study of consumer and environmental regulation in the EU and the US suggests that American regulation in these spheres is no longer exceptional. It is an interesting account since the study doesn’t resort to either the ‘catching up’ or the ‘convergence’ arguments. See David Vogel, ‘The Hare and the Tortoise Revisited’, British Journal of Political Science, 33 (October 2003), 557-580. 3 Giandomenico Majone, ‘The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe’, West European Politics 17 (1994), 77-101;. Giandomenico Majone, ‘From the Positive to the Regulatory State. Causes and Consequences of Changes in the Mode of Governance’, Journal of Public Policy, 17(2) (1997), 139-167. On the European continent, most attention to the ‘regulatory state’ in Europe is paid in relation to EUlevel development. Important exceptions are Müller, M. Markus, The New Regulatory State in Germany (Birmingham: Birmingham University Press, 2002) and some papers in the special issue of West European Politics, Vol. 25, 1 (2002), edited by Thatcher and Stone-Sweet. 4 Jacint, Jordana and Levi-Faur, David, ‘The Rise of the Regulatory State in Latin America’, presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, 26 (Philadelphia, 28-31 August 2003); Manzetti, Luigi (Ed.), Regulatory Policy in Latin America: Post-Privatization Realities (Miami: North-South Center Press, 2000). 5 Jayasuriya, Kanishka, ‘Globalization and the Changing Architecture of the State: The Politics of the Regulatory State and the Politics of Negative Co-ordination’, Journal of European Public Policy, 8 (1) (2001), 101-123. 6 The term ‘independent regulatory authority’ is problematic as at most these agencies might be institutionally autonomous but in no way independent (in the sense of impenetrable). For some initial discussion of the difference between independence and autonomy, see Nordlinger, Eric, ‘Taking the State Seriously’, in: Weiner, M. & Huntington, P. S. (Eds.), Understanding Political Development (Little, Brown, Boston, 1987), 353-390. 7 Giandomenico Majone, ‘The Regulatory State and its Legitimacy Problems’, West European Politics, 22(1) (1999), 1-24. Giandomenico Majone, Two Logics of Delegation: Agency and Fiduciary Relations in EU Governance’, European Union Politics, 2 (1) (2001) 103-122. 8 A similar observation is found in the analysis of diffusion of adversarial legalism: see Kagan, Robert, and Axelrad Lee, ‘Adversarial Legalism: An International Perspective’, in: Nivola, Pietro (Ed.), Competitive Disadvantages Social Regulations and the Global Economy (Washington, Brookings Institution Press, D.C.,1997), pp. 146-202. And, R. Daniel Keleman Rise of Adversarial Legalism in the European Union: Beyond Policy Learning and Regulatory Competition In: David Levi-Faur and Vigoda-Gadot Eran (Eds) International Public Policy and Management: Policy Learning Beyond Regional, Cultural and Political Boundaries, (Marcel Dekker, Forthcoming October 2004). 9 The notions of meta-regulation and enforced self-regulation are elaborated below. 27 10 Plainly put, states are embedded in societies and therefore we can expect that long- term changes will be reflected and manifested in both these ‘imaginary’ entities. For further exploration of this approach, see, Joel Migdal, State in Society: Studying how States and Societies Transform and Constitute One Another (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001). 11 Moran, p. 2. Our reference to the British regulatory state overlooks some of the implications of the devolution process. This process exposes much of Scotland and Northern Ireland to particular developments that are overlooked here. See Midwinter, Arthur, and McGarvey, Neil, ‘In Search of the Regulatory State: Evidence from Scotland’, Public Administration, 79(4) (2001), pp. 825-849. 12 On the American regulatory state, see Eisner, Marc Allen, Regulatory Politics in Transition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2nd ed, 2000). 13 See Majone, The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe; Majone, The Regulatory State and its Legitimacy Problems. 14 The reference here applies generally to the ‘Australian School of Regulation’ around RegNet, the Australian National University, and the works of John Braithwaite and his colleagues. See also Gunningham, Neil, and Peter N. Grabosky, Smart Regulation: Designing Environmental Policy (Oxford: Clarendon, 1998). 15 Or Risk Society: see Richard V. Ericson & Kevin D. Haggerty, Policing the Risk Society (University of Toronto Press, 1997). 16 Moran, p. 4. 17 Moran, p. 68. 28 18 Moran, p. 4. The term ‘club government’ is borrowed from David Marquand: ‘The atmosphere of British government was that of a club, whose members trusted each other to observe the spirit of the club rules; the notion that the principles underlying the rules should be clearly defined and publicly proclaimed was profoundly alien.’ David Marquand, The Unprincipled Society: New Demands and Old Politics (London, Cape, 1988) p. 178. The term echoes the informalities of British governance as formulated by Heclo H. and Wildavsky A., The Private Government of Public Money (London, Macmillan, 1974). 19 Moran, p. 41-42 20 Moran, p. 31. 21 Moran, p. 42. 22 Moran, p. 9. 23 Moran, p. 9. 24 Moran, p. 20-22. 25 Moran, p. 7. 26 Moran, p. 20-21. 27 Moran, pp. 6 and 8. Moran bases his case here on James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). 28 Moran, p. 179. 29 29 Hood et al., p. 23. 30 Hood et al, p. 27. 31 Hood et al, p 27. 32 Hood et al., pp. 29-31. 33 Hood et al, p. 42. 34 Peter Grabosky and John Braithwaite, Of Manners Gentle: Enforcement Strategies of Australian Business Regulatory Agencies (Melbourne; New York: Oxford University Press in association with Australian Institute of Criminology, 1986). 35 Donald J. Black, The Behavior of Law (New York: Academic Press, 1976), p. 40. 36 In contrast, research done on Australian regulatory agencies found no correlation between frequency of interaction and industry background on the one hand and the level of enforcement (i.e., the use of sanctions vs. softer types of enforcement) on the other. Grabosky and Braithwaite (1986) found the number and size of firms in the sector to be the best predictors of enforcement; Peter Grabosky and John Braithwaite, 1986, Of Manners Gentle; Makkai and Braithwaite (1995); Makkai T., and Braithwaite John. 1995, ‘In and out of the Revolving Door: Making Sense of Regulatory Capture’. Journal of Public Policy, 1: 61-78. 37 Power, p. 4. 38 Power, p. 14. 30 39 Power, p. xii 40 Power, p. 11 41 Power, p.68. 42 Power, p. 2; p. 3. 43 This fourth feature – the creation of a multi-layered regulatory system of regulation and self-regulation – rests on Foucault’s notion of governmentality, and socio-legal studies’ insight of self-regulation as the internalization of external norms. Rose argues that for Foucault government is ‘all endeavors to shape, guide, direct the conduct of others…and it also embraces the ways in which one might be urged and educated…to govern oneself’ (Rose, Nikolas S. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 3). Consequently, we should be aware that state regulation is only one element – though critical – in multiple circuits of power and public controls. These new scholarly insights resulted in a new interpretation of mechanisms that were always there. Indeed, it was the earlier simplistic distinction between regulation and self-regulation that impeded our understanding of self-regulation as a means of social control. 44 Cf. the three characteristics: (partial) shift in ownership to the private sector, the creation of quasi-independent agencies, and the formalization of relationships within the policy domain (Loughlin, Martin, and Colin Scott, (1997) ‘The Regulatory State’, in Patrick Dunleavy, Ian Holliday, Andrew Gamble, and Gillian Peele (eds.), Developments in British Politics 5. Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 205-219). Also the following characterization: ‘We can now build a picture of the regulatory state: it is one which attaches relatively more importance to process of regulation than to other means of policy making. The regulatory state is a rule-making state, with an attachment to the rule of law and, normally, a predilection for judicial or quasi-judicial 31 solutions’ (McGowan, F. and Wallace, H. ‘Towards a European Regulatory State’, Journal of European Public Policy, 3, (4) (1996), p. 563). 45 Osborne, David and Gaebler, Ted, Reinventing Government (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1992). 46 Majone, From the Positive to the Regulatory State, pp. 148-9. 47 G. Majone, ‘Public Policy and Administration: Ideas, Interests and Institutions’, in: Goodin E. Robert and Klingemann, Hans-Dieter (Eds.), A New Handbook of Political Science (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 611. 48 Hood et al. 107. 49 Grabosky and Braithwaite, Of Manners Gentle. 50 Philip Selznick, TVA and the Grass Roots; A Study in the Sociology of Formal Organization (New York,: Harper & Row. 1966); Blau, Peter Michael. 1963. The dynamics of bureaucracy; a study of interpersonal relations in two Government agencies. Rev. 2d ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 51 Rainier Kraakman, ‘Gatekeepers: The Anatomy of a Third-Party Enforcement Strategy’, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 2, (1986), 53-104. 52 Peter, Grabosky, ‘The System of Corporate Crime Control’, in: Pontell N. Henry and Shichor David, Contemporary Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2001), p. 148. 53 Self-regulate, or else..’ seems to be state strategy. See Ayres, Ian, and John Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 15). 32 54 55 Ayres and Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation, p. 101-132. Morgan, Bronwen, Social Citizenship in the Shadow of Competition: The Bureaucratic Politics of Regulatory Justification, Law, justice, and Power. (Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Dartmouth, 2003) p. 2; see also, Parker, Christine, The Open Corporation: Effective Self-Regulation and Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002). 56 Ayres and Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation. 57 For a critical account of this assertion see, Scott, Colin, ‘Regulation in the Age of Governance: The Rise of the Post-Regulatory State’, in Jordana Jacint and Levi-Faur David (Eds.), The Politics of Regulation in the Age of Governance, Elgar and the Centre on Regulation and Competition, University of Manchester. 58 This multi-layered system is not in any form a product of efficient rational design. Moran argues, ‘the history of the state is marked by anything but the measured selection of regulatory institutions and instruments. It is marked instead by crisis and chaos’ (Moran, p. 26). 59 It is noteworthy that Hood et al. explicitly state that their ‘analysis has been more concerned with how these developments occurred than why they occurred’ (Hood et al., p. 209), although, in effect, they supply a great deal of explanation. 60 ‘The literature offers a confusing potpourri of definitions applied to a host of units and level of analysis.’ Shapiro, Susan. ‘The Social Control of impersonal Trust’. American Journal of Sociology 93(3) (1987), 625. On an inter-personal level, Gambetta (1988), for example, views trust as a subjective expectation that the likelihood that another agent will perform a particular action that is beneficial (or not detrimental) to us, and our confidence in her knowledge and expertise to perform such 33 action are high enough for us to consider engaging in some form of cooperation with her. Diego Gambetta (ed.), Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations (New York: B. Blackwell 1988, p. 219). Shapiro, 1987, 634, inquires into ‘impersonal trust’, which is relevant when direct contact between principal and agent are unavailable. 61 ‘It is mistaken to regard trust as an element in primary group control, since the hallmarks of the simpler systems of primacy group control are surveillance, the absence of privacy, and coercion.… Very simply put, where one cannot directly observe, yet seeks to control, the principal substitutes are collateral security and trust. The basic contention is that modern societies and their organizations are increasingly built on complex trust relationships.’ Reiss, Albert, ‘Selecting Strategies of Social Control over Organizational Life’, in Enforcing Regulation, edited by K. Hawkins and J. M. Thomas (Boston Hingham, Mass.: Kluwer-Nijhoff, 1984.), p. 33. 62 Gambetta, Trust, p. 219. 63 Hood et al., p. 202. 64 In other cases the reason seems to stem from partisan politics and politicians’ distrust of regulators. This seems be the case of school regulation, where the Thatcher and Major administrations perceived the professional education establishment as leftleaning. Hood et al., p. 147. 65 66 Hood et al., p. 103. However, our discussion above regarding change in regulators-regulatees relationships, explicates that behind what looks as rule-bound adversarial relationship we may still find interdependent informal cooperation. 67 Power, p. 14. 34 68 Moran, p. 155. 69 Moran, p. 116. 70 Moran, p. 26. 71 Moran, p. 162. 72 Moran, p. 183. 73 Hood et al., p. 33. 74 Hood et al., p. 34. 75 Power, p. 14. 76 ‘Power, p. 2. 77 Power, p. 91. 78 Cf. ‘[T]here are few projects more central to the social sciences than the study of regulation’ (Braithwaite J, and Drahos P. Global Business Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (2000), p. 10. 79 Meseguer, Covadonga, ‘The Diffusion of Privatisation in Industrial and Latin American Countries: What Role For Learning?’ Prepared for delivery at the workshop on the Internationalization of Regulatory Reforms: The Interaction of Policy Learning and Policy Emulation in Diffusion Processes, Berkeley (April 24-25 2003). Brune, Nancy and Geoffrey Garrett, ‘The Diffusion of Privatization in the Developing World’, Prepared for presentation at the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association, Washington (August 30-September 3, 2000). 35 80 Levi-Faur, David, Herding towards a New Convention: On Herds, Shepherds, and Lost Sheep in the Liberalization of the Telecommunications and Electricity Industries, Politics Papers Series (Nuffield College, University of Oxford, W6-2002. Another study of 19 Latin American countries in 12 different sectors found that from a meagre number of regulatory authorities in 1988 (mostly in the financial sectors), the overall number of regulatory authorities (with varying degrees of autonomy) had grown to 134 by 2002. In the four years from 1993 to 1996, 60 new authorities were established. All sectors and countries were affected by the process . Jordana and LeviFaur, The Regulatory State in Latin America. 81 The data cover the following sectors: Competition, Financial Services, Telecoms, Electricity, Environment, Food Safety and Pharmaceutical. The countries are the 19 that were studied by Jordan and Levi-Faur, The Regulatory State in Latin America as well as 17 European Countries that were studied by Fabrizio Gilardi. See his outstanding dissertation: Delegation to Independent Regulatory Agencies in Western Europe, Thesis at the University of Lausanne, 2004. We are grateful for Fabrizio Gilardi’s data. 82 Notable exception is Polit, Christopher et al., Performance or Compliance? - Performance Audit and Public Management in Five Countries (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999). The study covers France, Finland, The Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK. For the Audit Society in Australia, see Scott, Colin, ‘Speaking Softly without Big Sticks: Metaregulation and Public Sector Audit’, Law and Policy 25 (2003), pp. 203-219. 36