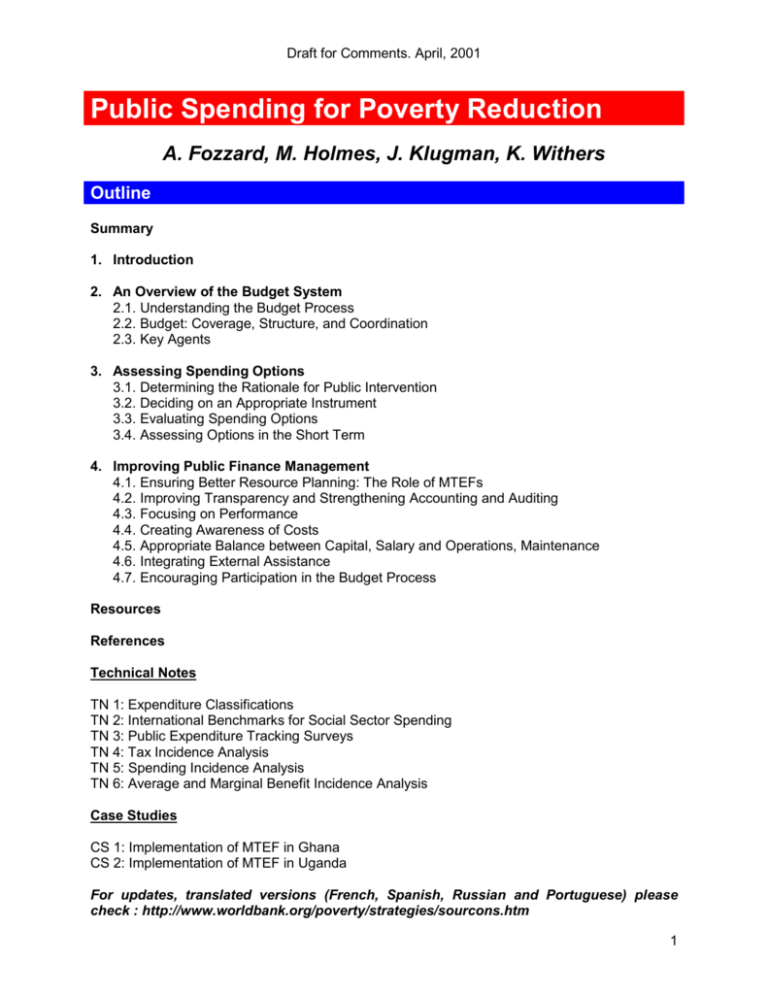

Public Spending for Poverty Reduction

advertisement