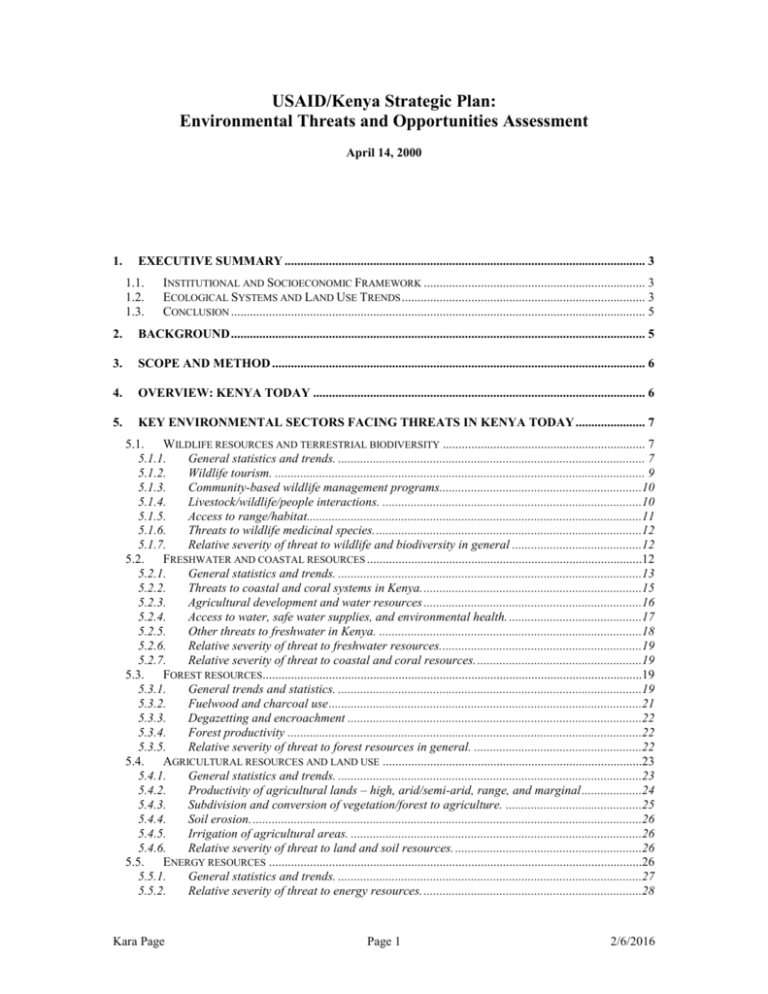

USAID/Kenya Environmental Threats and Opportunities

advertisement