Natural vegetation change, ecosystems and soil

Natural vegetation change, ecosystems and soil types.

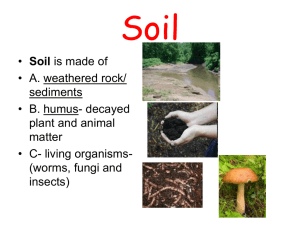

Factors in soil formation

Various factors are involved in soil formation: time, geology, relief, drainage, climate, vegetation and people.

Time

It takes about 1000 years for one centimetre of soil to form. In many parts of Britain we have had only 10,000 years since the last

Ice Age stripped the original surface soils away.

Geology

Minerals from the parent material are added to the soil by physical and chemical weathering.

Relief

Different soils will form on different degrees of slope and aspect.

Gravity and temperatures will affect the degree of slope movement and weathering.

Drainage

Whether water can or cannot move through the soil easily will affect the development of the soil profile.

Climate

How much water and air enter the soil - and their temperatures - will affect the organic life of the soil and evaporation rates on the surface.

Vegetation

The type and quantity of plant cover will affect the amount of organic material added to the soil (humus).

People

When people change the angle of a slope through construction, or change the vegetation cover and/or drainage in an area, the soil will also change.

Soil profiles

You need to be able to recognise the three British soils; podzol, brown earth and gley. For each of them, you should also be able to describe and explain their formation.

Podzol

Podzol soil showing dpistinctive layers

Podzols are easily recognisable by their distinct layers or horizons.

A grey or light-coloured 'E' horizon is the result of severe leaching, or eluviation , which washes out everything but quartz grains.

The iron and aluminium oxides collect in the 'B' horizon ( illuviation ) where the iron oxides can accumulate to form a thin layer of hardpan, which impedes drainage through the soil.

Some iron and aluminium oxides get through the iron/hardpan, giving this 'B' horizon its dull orange colour.

These soils are found where there is good drainage and soil water is strongly acidic. They tend to be found on the upper slopes of upland areas where precipitation is heavy or where the vegetation is coniferous forest, producing an acid humus. The acid conditions are not liked by soil organisms which would normally mix/merge the boundaries of the horizons.

Brown Earth

A typical example of brown soil

Brown earth soils are widespread in Britain, except in highland areas.

Soil organisms, like earthworms, mix the materials together, merging the boundaries between the horizons.

These soils are leached, but not heavily, so the aluminium and iron oxides are dispersed through the soil to give the overall brown colour.

The original vegetation was deciduous forest, resulting in a layer of decaying leaves giving a rich humus. The deep roots of these trees reached down to the 'B' horizon (unlike coniferous trees) tapping the nutrient supply and allowing good drainage.

Gley

A typical example of gley soil

Gley soils represent the most extensive soil cover in Scotland.

These soils are found on gentler slopes or in areas of high rainfall where the water does not drain away very readily. All the glacial tills of central Scotland are dominated by gley soils.

Peaty gley soil is waterlogged for all or most of the year. This waterlogging denies the soil the oxygen that the soil organisms need to survive.

The organisms left in the soil extract the oxygen they need to survive from the iron compounds and the soil gradually turns grey, blue or green as the oxygen is depleted.

If only the surface is badly drained (in spring melt water areas), the soil is called a surface water gley. If the water permeates the soil all year, it is called a ground water gley. If construction work in urban areas disrupts the soil drainage it is called an urban gley.

Vegetation

Stages of Succession

You need to be able to describe and explain the development of a special ecosystem - sand dunes.

You should also be able to describe and explain the adaptations that plant species have made to cope with the environment.

Sand dunes

At the pioneer stage, seeds are blown in by the wind or washed in by the sea. The rooting conditions are poor due to drought, strong winds, salty sea-water immersion and alkali conditions created by sea shells. The wind moves sand in the dunes and this allows rainwater to soak through rapidly.

At the building stage, plants trap sand and grow with it, binding the sand together with their roots. The humus created by decaying pioneer plants creates more fertile growing conditions, and the soil becomes less alkaline as pioneer plants grow and trap rainwater.

Less hardy plants can now grow and start to shade out the pioneers. As plants colonise the dunes, the sand disappears and the dunes change colour - from yellow to grey.

At the climax stage, taller plants (such as trees) and more complex plant species (like moorland heathers) can now grow.

Plants from earlier stages die out because of competition for light and water. When the water table reaches or nearly reaches the surface, dune slacks can occur. Plants which are specially adapted to be water-tolerant grow here.