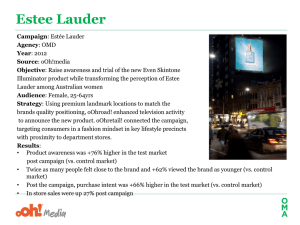

Cities Fit for Cycling campaign of The Times newspaper

advertisement

Cities Fit for Cycling campaign of The Times newspaper The Times newspaper of London kicked off a cycling safety campaign in early February, 2012, with a front-page article decrying the hazardous conditions of UK roads and a clarion headline: “Save Our Cyclists.” An opinion piece by the newspaper’s editor noted that in order to cycle in the UK, cyclists must be fit for cities. He wrote that it was about time to turn this axiom on its head, and to demand that cities be fit for cycling. Thusly dubbed “Cities Fit for Cycling,” the campaign involves targeted coverage of cyclingsafety stories on the paper’s newspages and website, a published manifesto of eight specific cycling-safety measures to be embraced by public authorities, a web facility assisting readers in putting pressure on their MPs, and a drive to get publicly-pledged support from readers. Because it is a newspaper campaign, its default target audience is the broad, reading public. However, the campaign’s messages aim at a few specific audiences: First and foremost are elected officials. Every one of the eight points of the cycling-safety manifesto calls on political leaders to take action, whether it be to lower speed limits in residential areas; regulate lorry traffic; invest in safer road infrastructure or make a national audit of traffic crashes involving bicyclists. These calls are aimed not only at MPs but also at local authorities, who have competence in local traffic matters. The campaign also brings a message to drivers, raising awareness of how they modify their conduct so that cars and cyclists can share road space safely. Several articles in the campaign’s specialized coverage focus on the problem of lorries and other heavy goods vehicles, pointing out the disproportionate share of cyclist injuries and deaths that involve large vehicles. The first manifesto point calls for special regulation of HVGs that frequent urban street networks. The campaign has one plaudits from cycling groups around the UK and abroad for its recognition that cycling safety can’t be achieved by cyclists alone. Accommodation must be made by other road users and by public authorities at all levels in order to create a safer atmosphere for cycling: Cities must become fit for cycling. The inspiration for the campaign was personal. A staff writer for The Times, a young woman named Mary Bowers, suffered traumatic injuries to her head, pelvis and limbs just metres from The Times offices in central London when she was struck by a lorry while riding to work. At the time The Times campaign got underway, Bowers had been unconscious in a hospital trauma ward for approximately three months, and her recovery was anything but certain. With such a horrific origin, it is unsurprising that the campaign has had a combative, defensive bent. In an otherwise laudatory piece, a blogger for the Guardian newspaper, James Randerson, noted that the campaign’s mordant focus on road dangers could have the perverse effect of discouraging people from cycling. “There is much discussion about the dangers and anecdotes about collisions but not enough about the joy of getting around on two wheels,” Randerson observed. Nonetheless, the campaign marked a cultural breakthrough for the nascent cycling movement in Britain. It hasn’t been long since cyclists in London were seen as part of the lunatic fringe, but after garnering the support of successive mayors and now the country’s premier mainstream newspaper, cyclists can now also be seen as mainstream. Though the campaign was little more than a month old at the time of this writing, it had garnered several good results. These included: 30,000 readers having formally registered their support for the campaign; 1,700 letters sent to MPs; public declarations of support by several prominent athletes and politicians including British Prime Ministrer David Cameron, London Mayor Boris Johnson as well as other candidate in for the 2012 mayoral election; the holding of a February Parliamentary debate concerning the campaign drew 77 MPs, including 35 Conservatives, 29 Labour politicians and 13 Liberal Democrats; a letter sent to all local councils in Britain by Norman Baker, Transport Minister, and Mike Penning, Road Safety Minister. In addition the opposition Labour party had vowed to reinstate road safety targets that had earlier been abandoned by the Conservative Government. In 2000, Labour set a 10-year target of reducing by 40 percent the number of people killed or seriously injured on the roads. The target was surpassed and a reduction of 49 percent secured.