iwsf environmental handbook - International Water Ski Federation

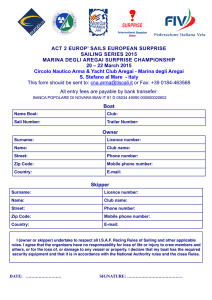

advertisement