G. Include Opportunity Costs: Include opportunity cost cash flows

CHAPTER 9

USING DISCOUNTED CASH-FLOW

ANALYSIS TO MAKE INVESTMENT

DECISIONS

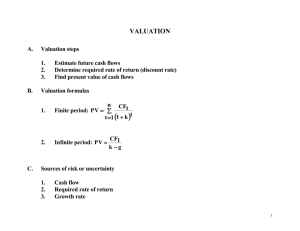

CHAPTER IN PERSPECTIVE

This chapter builds upon the last chapter and focuses on estimating the expected cash flows of an investment project. There are a number of general concepts and rather detailed procedures that a student must master. One of the more important concepts is that of determining the “incremental” cash-flow impact of a new project. The standard question for the student to ask is, “What changes, given the decision to make the investment?” The Blooper Industries example is a good discussion example that enables one to cover most of the concepts and rules developed in the chapter. When working the cash-flows examples, complete the analysis with an assessment of the NPV and IRR and their corresponding decision rules. This enables the student to tie the last chapter and this one into a continuous process.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

9.1 IDENTIFYING CASH FLOWS

Discount Cash Flows, Not Profit

Discount Incremental Cash Flows

Discount Nominal Cash Flows by the Nominal Cost of Capital

Separate Investment and Financing Decisions

9.2 CALCULATING CASH FLOW

Capital Investment

Investment in Working Capital

Operating Cash Flow

81

9.3 AN EXAMPLE: BLOOPER INDUSTRIES

Cash Flow Analysis

Calculating the NPV of Blooper’s Project

Further Notes and Wrinkles Arising from Blooper’s Project

TOPIC OUTLINE, KEY LECTURE CONCEPTS, AND TERMS

9.1 IDENTIFYING CASH FLOWS

Discount Cash Flows, Not Profits

A. Income statements measure historical performance according to generally accepted accounting principles, not in cash-flow terms.

B. Cash flows, when they occur, discounted at the opportunity rate of return is the proper method for net present value.

Discount Incremental Cash Flows

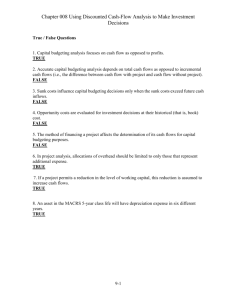

A. Project cash-flow analysis should consider the differential cash flows that occur given the acceptance of the project.

B. Incremental cash flows represent the cash-flow changes that the new project creates, or the cash flow with the project less the cash flow without the project.

C. Include All Direct Effects: All differential cash-flow implications of the project must be considered, including the impact of the new project on any other aspect of the business cash flows.

D. Forget Sunk Costs : Cash flows not related to the project are irrelevant in the project cash-flow analysis.

F. Cash flows that occur regardless of whether the project investment is made are sunk costs and are not relevant to the current project.

G. Include Opportunity Costs : Include opportunity cost cash flows, such as the

82

value of land that you could otherwise sell, as a relevant cost of an investment project.

H. The opportunity cost, or the best alternative value option of the land owned prior to the investment consideration, is a part of the investment outlay.

I.

Recognize the Investment in Working Capital : The incremental net working capital , added current assets less added current liabilities, represents relevant cash-flow costs of initiating a project and should be part of the NPV analysis.

Working capital recovered at the end of the project is a relevant cash flow.

J. Ignoring working capital, or the fact that varying levels of incremental net working capital may occur throughout the life of the project, or ignoring the recovery of working capital are three common errors in project cash-flow analysis.

K. Beware of Allocated Overhead Costs : Overhead costs, such as heat and lights, incurred whether the project investment is made or not, are irrelevant to the project cash-flow analysis.

L. Include only the additional or incremental cash-flow cost, only when they occur, in the project analysis.

Discount Nominal Cash Flows by the Nominal Cost of Capital

A. If the discount rate or the opportunity rate of return used in project analysis is in nominal terms, versus inflation adjusted or in real terms, relevant project cash flows should be in nominal terms as well. One may use real, inflation adjusted discount rates and cash flows, but consistency in this matter is what is important.

B. Expected cash flows, if inflation is expected during the life of the project, must be adjusted upward to nominal values. The adjustment should reflect the added price changes in the prices of the products, labor costs, etc., rather than a general inflation rate, such as the Consumer Price Index.

Separate Investment and Financing Decisions

A. When the cash flows of an investment are analyzed, how the investment is financed, or the financing costs of the project, is ignored.

B. How the project is financed, and the financing costs, are variables affecting the opportunity rate of return, used to discount the cash flows. Financing the project and its impact is considered when calculating the opportunity rate of return, studied later in the book.

83

C. The value of the investment is considered by itself, independent of financing choice.

9.2

CALCULATING CASH FLOW

Total cash flow from a project includes cash flows from three sources:

A. Cash flows associated with investment in plant and equipment.

B. Cash flows associated with investments in added net working capital.

C. Cash flows from operations.

Capital Investment

Net capital investment cash flows often include:

A. Cost of equipment and conditioning for operation.

B. If a replacement project, sale of the old equipment.

C. If a replacement project, the tax effect of selling old

equipment.

Investment in Working Capital

Net working capital cash flows include:

A. Incremental changes in working capital investments such as

account receivables and inventory, given the decision to

invest in the new project.

B. Working capital investments (assets) adjusted for changes

in added payables and other spontaneous accruals.

Cash Flows from Operations

Incremental cash flows from operations may be calculated three ways:

A. Calculate the annual cash flow from operations using an

84

incremental cash flow statement.

Cash flow from operations = cash revenues – cash expenses – cash taxes

B. Calculate the annual net income and add back noncash expenses to determine cash flow from operations.

Cash flow from operations = incremental net profit + incremental depreciation

C. Calculate the after-tax amount of each type of cash flow, then sum for the year.

D. The depreciation tax shield, or the net cash flow from reduced taxes from depreciation expenses, is the product of the amount of incremental depreciation times the tax rate.

Depreciation tax shield = incremental depreciation x tax rate

9.3 EXAMPLE: BLOOPER INDUSTRIES

Work carefully through the Blooper Industries example, reinforcing concepts mentioned earlier. See Table 9.1.

Cash Flow Analysis

A. All of the outlay, $10 million, is assumed to be made now or in the zero period, with no salvage value expected at the end of the project life.

B. Note the changes in net working capital, or net added current assets needed, early in the project. Later, as the project winds down, net current assets are no longer needed and contribute to the positive cash flow.

C. Revenues are estimated through the periods in which revenues are thought to be generated. Do not arbitrarily cut-off the periods of cash-flow generation.

D. Lines four and five are assumed to be cash flow revenue and expenses, with depreciation to be the only noncash revenue/expense in the analysis.

E. Project cash flows are the sum of three components: investment outlay of the project, investment in project net working capital, and project cash flow from operations.

F. Cash flows from operations may be determined from the Table 9.1 data two ways: calculate the sum of cash inflows and outflows, or add back depreciation (noncash

85

expense) to net after-tax profit.

Calculating the NPV of Blooper’s Project

Cash flows are conservatively assumed to occur at the end of the year.

Further Notes and Wrinkles Arising from Blooper’s Project

A. Nominal annual depreciation amounts, given inflation, yield lower real tax shield cash flow.

Recovery Period Class

Year(s) 3-Year 5-Year 7-Year 10-Year 15-Year 20-Year

1 33.33 20.00 14.29 10.00 5.00 3.75

11

12

13

14

15

16

17-20

21

7

8

9

10

2

3

4

5

6

44.45

14.81

7.41

32.00

19.20

11.52

11.52

5.76

24.49

17.49

12.49

8.93

8.93

8.93

4.45

18.00

14.40

11.52

9.22

7.37

6.55

6.55

6.55

6.55

3.29

9.50

8.55

7.70

6.93

6.23

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

5.90

2.99

4.46

4.46

4.46

4.46

4.46

4.46

4.46

2.25

7.22

6.68

6.18

5.71

5.28

4.89

4.52

4.46

4.46

B.

Congress established depreciation schedules, called the modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) , that provide an accelerated rate of depreciation, depending on the class of asset, which offsets the reduced real value of the tax shield when inflation exists.

See Table 9.2 for the modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) schedules.

C. The half-year convention assumes, in the 5-year class, that the asset was purchased at mid-point of the first year, provides one-half depreciation the first year and the sixth year.

D. The MACRS provides a faster depreciation rate (double-declining balance) and

86

tax shield recovery compared to the straight-line depreciation rate, which provides for equal depreciation amounts over the useful life of the project. See

Table 9.3.

Year

Straight-Line Depreciation

Depreciatio n

2,000

Tax

Shield

700

PV Tax

Shield

At 12%

625

MACRS Depreciation

Depreciatio n

2,000

Tax

Shield

700

PV Tax

Shield

At 12%

625 1

2

3

4

5

2,000

2,000

2,000

2,000

700

700

700

700

558

498

445

397

3,200

1,920

1,152

1,152

1,120

672

403

403

893

478

256

229

6

Totals

0

10,000

0

3,500

0

2,523

576

10,000

202

3,500

102

2,583

E. The MACRS depreciation tax shield affects cash flow, and is relevant for capital budgeting analysis.

F. Salvage value cash flows involve the net cash received from the disposal less any taxes (sold for more than book value) on the sale or plus any tax shield (sold for less than book value) loss (book loss times the marginal tax rate).

PEDAGOGICAL IDEAS

General Teaching Note One of the key concepts developed in this chapter is the process of determining the relevant, incremental cash flows of an investment. From outlay, periodic and final period, this general question applies: “What changes, given our decision to make the investment?” With this concept in mind the after-tax, sunk cost, and other concepts are easier to understand, so the suggestion is to start with the

“incremental” concept.

Student Career Planning All students are familiar with the business cycle, and most have watched its effect upon their family members. They have studied it in business cases and have seen its effect upon the businesses in the cases they have studied. They now have to watch it with great personal interest. The state of the economy or industry when they graduate will affect the number and variety of entrylevel jobs available. Chances are very good that economic conditions have changed, either better or worse, since they declared their major. They need to be reminded to keep up with the economy and industries where they have an interest and to read periodicals related to the industry in question on a regular basis and, of course, their

WSJ .

Wall Street Journal Focus The classified ads of The Wall Street Journal , entitled

“The Mart,” provide students with a look at life several years down the road. Almost

87

all of the personnel references, such as positions available and placement services, are for experienced managers. The jobs available and advertised are varied, as are the salaries, and it is interesting to look at the specialties the student may develop in the next few years. Share with your students the confidence that they will be there in just a short period. The people applying for the jobs in “The Mart” were students like your students just a few years ago. Tell them to keep their eye on the “New Business

Offering,” listing franchise and other business opportunities. Encourage them to call a few 800 numbers and request information on new franchise opportunities. What capital and experience does it require? Would such a business be successful in their area? The student should know that having their own business starts as a long-term plan, and for the few special people that will start or buy their own business one day, and create their own job, it is never too soon to think about it and plan.

Using Accompanying Videotapes - The video, “Capital Budgeting,” is an excellent way to reinforce the concepts and terms of the chapter, but there is more! The video features Navistar Corporation (large truck manufacturer) and a “new” approach to capital budgeting. Instead of planning for capital expenditures, separate from the operating budget, Navistar includes capital expenditure planning as a part of their overall business plan. With operational and capital expenditures, focused around their strategic objectives, managers are given the flexibility to adapt to market changes, environmental and regulatory concerns, and customer needs.

Before the video is shown , briefly discuss the traditional capital budgeting process as separate from operating budgets and “top down” decision making. Ask students to look for the following:

1. How has Navistar changed the traditional capital budgeting process?

2. What are the decision rules used by the company?

3. Where are shareholder interests, concerns, and minimum returns

included in Navistar’s capital expenditure program?

After the video is shown , discuss the above questions in a general discussion or in small groups. Note the inclusion or many stakeholders in the evaluation, including shareholder interests in increasing value and providing competitive rates of return. As a follow-up, consider the following questions:

1. How has changing the capital budgeting procedures improved

Navistar’s ability to increase shareholder value?

2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of decentralizing capital

budgeting decisions?

3. What example in the video reinforces the idea that capital budgeting or

planning might change the operational methods of the company?

88