Group 3: Ocean zoning (Ocean Management Areas) and E-bFM

advertisement

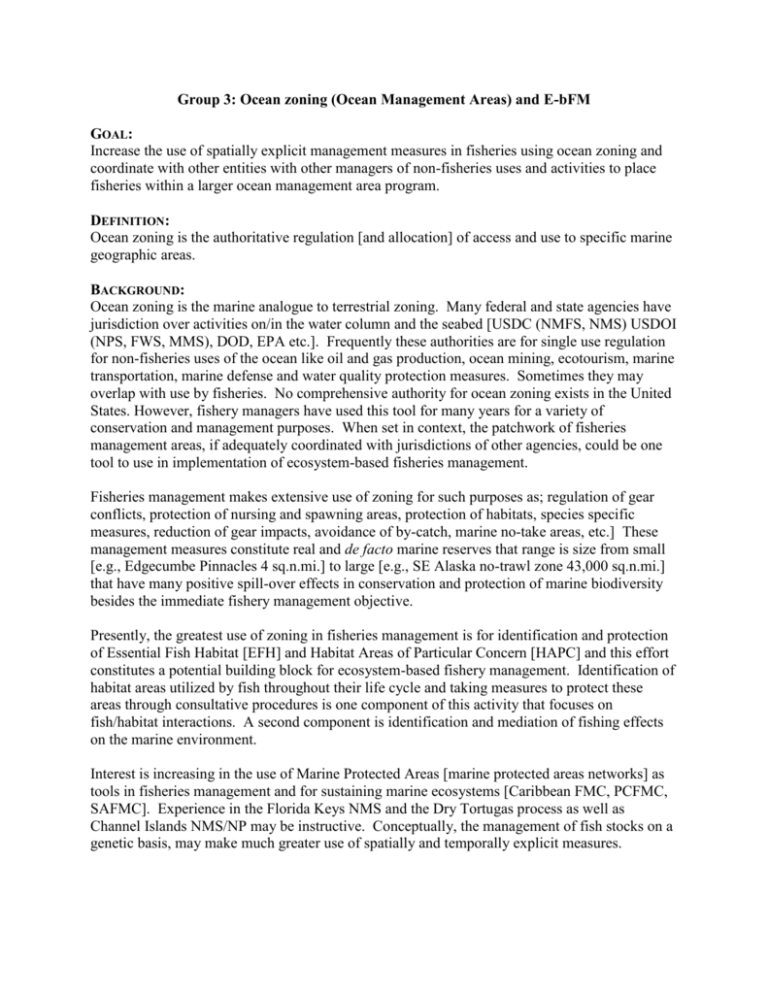

Group 3: Ocean zoning (Ocean Management Areas) and E-bFM GOAL: Increase the use of spatially explicit management measures in fisheries using ocean zoning and coordinate with other entities with other managers of non-fisheries uses and activities to place fisheries within a larger ocean management area program. DEFINITION: Ocean zoning is the authoritative regulation [and allocation] of access and use to specific marine geographic areas. BACKGROUND: Ocean zoning is the marine analogue to terrestrial zoning. Many federal and state agencies have jurisdiction over activities on/in the water column and the seabed [USDC (NMFS, NMS) USDOI (NPS, FWS, MMS), DOD, EPA etc.]. Frequently these authorities are for single use regulation for non-fisheries uses of the ocean like oil and gas production, ocean mining, ecotourism, marine transportation, marine defense and water quality protection measures. Sometimes they may overlap with use by fisheries. No comprehensive authority for ocean zoning exists in the United States. However, fishery managers have used this tool for many years for a variety of conservation and management purposes. When set in context, the patchwork of fisheries management areas, if adequately coordinated with jurisdictions of other agencies, could be one tool to use in implementation of ecosystem-based fisheries management. Fisheries management makes extensive use of zoning for such purposes as; regulation of gear conflicts, protection of nursing and spawning areas, protection of habitats, species specific measures, reduction of gear impacts, avoidance of by-catch, marine no-take areas, etc.] These management measures constitute real and de facto marine reserves that range is size from small [e.g., Edgecumbe Pinnacles 4 sq.n.mi.] to large [e.g., SE Alaska no-trawl zone 43,000 sq.n.mi.] that have many positive spill-over effects in conservation and protection of marine biodiversity besides the immediate fishery management objective. Presently, the greatest use of zoning in fisheries management is for identification and protection of Essential Fish Habitat [EFH] and Habitat Areas of Particular Concern [HAPC] and this effort constitutes a potential building block for ecosystem-based fishery management. Identification of habitat areas utilized by fish throughout their life cycle and taking measures to protect these areas through consultative procedures is one component of this activity that focuses on fish/habitat interactions. A second component is identification and mediation of fishing effects on the marine environment. Interest is increasing in the use of Marine Protected Areas [marine protected areas networks] as tools in fisheries management and for sustaining marine ecosystems [Caribbean FMC, PCFMC, SAFMC]. Experience in the Florida Keys NMS and the Dry Tortugas process as well as Channel Islands NMS/NP may be instructive. Conceptually, the management of fish stocks on a genetic basis, may make much greater use of spatially and temporally explicit measures. Fisheries management may increasingly need to form partnerships with other agencies with marine management jurisdictions. Examples of potential cooperation [in some cases expanding on existing relationships, e.g., consultative requirements under the FWCA, NEPA, with MMS, EPA] are many and can be explored. Given that marine ecosystems extend across federal and state boundaries and can be dependent on watershed and estuarine areas consideration needs to be given to mechanisms for coordination among local, state, tribal and federal jurisdictions. Some states, Oregon, Florida ? and Maryland ? have already developed zoning for their territorial seas. The Oceans Commission 2000 has on its agenda the investigation of marine zoning. Internationally, Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management [ICOM] is gaining ground as a concept for management of competing uses in marine areas. It employs ocean zoning as a major tool. OCEAN ZONING – NEXT STEPS Further exploration of opportunities for use of ocean zoning as part of an ecosystem-based fishery management approach. 1. Identification and systematic assessment of the existing use of geographically based fishery management measures in the US, including EFH. Document and map using GIS. Assessment could consider how areas and habitats are protected from fishing and other impacts as well as consider how fisheries are given priorities in certain areas [e.g., gear limited areas] (link Group 2, 4) 2. Examination of state-level and foreign country experience with ocean area zoning for multiple uses, including fisheries and for fisheries within comprehensive ocean plans [e.g., Australia, Philippines, South Africa] for possible models. 3. Research on hierarchical relationships/ marine zoning on different spatial scales. (link Group 2) 4. Research on spatially explicit management measures for fishing in areas surrounding/outside of marine reserves [fully-protected, partially protected]. (link Group 2) 5. Development of technologies required to implement large scale spatially explicit fisheries management, e.g., GIS tools, vessel tracking and positioning equipment. 6. Explore social patterns of use and social components of geographic-based mgmt measures (link Group 1,6) 7. Examine interagency [state, local, and tribal, incl domestic/international, and task forces] coord efforts for multiple zoning instances (link group 5) CASE STUDIES Possible Case studies of Great Lakes, Coastal Watershed Restoration [Mel Moon’s discussion], Chesapeake Bay Fisheries Ecosystem Plan, Caribbean Council’s MPAs in Virgin Islands. Oculina Banks. HOW TO MOVE AHEAD: 1. Identify, if necessary, additional members for Group 3 with suitable expertise. 2. Write White Paper/ component of report that focuses on spatially-based fisheries management and evaluate effectiveness MPAs as a tool for managing fisheries in large regions [see Hastings and Botsford, Hannesson responses to Roberts et al. in Science] at commercial scale.