power point

Higher Geography Hydrosphere Drainage Basins

The Global Hydrological Cycle Name_ ____________

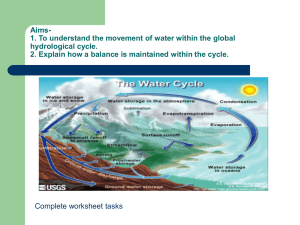

The global hydrological cycle is one of nature’s most important cycles. It explains distribution and movement of water all across the world. Essentially, the model involves a continuous circulation of water, either as a liquid, solid or as a vapour. The water moves between the atmosphere, vegetation and the land.

Solar power is the driving force behind the hydrological cycle. By heating up the oceans, lakes and rivers, water is evaporated into the atmosphere. All of this water-laden air is transferred into the air and carried by winds. When it cools, the condensation results in clouds. These eventually lead to precipitation which is usually either rain or snow.

Because two thirds of the planet’s surface is ocean, a lot of the precipitation lands on the sea and then evaporates again, representing a very quick turn-around to the hydrological cycle.

If it rains or snows on the land, however, it will take longer. Often trees act as interception, slowing the flow of water when they take the water into their own system. If the snow falls on high mountain tops it can often join an ice-cap or a glacier and be stored for several thousand years.

The water will always try to flow downhill back towards the rivers and then the sea. It manages this in a variety of ways. First, it

infiltrates the soil and is either stored as soil moisture or flows down through the soil as through-flow. If the water percolates further down into the rock it is stored as groundwater storage or moves down the slope as groundwater flow.

A faster flow of water is surface run-off, when water runs across the surface of the ground with little to interrupt it.

The hydrological cycle is a good example of a closed system: nothing can escape it. The total amount of water is always the same with virtually no water added or lost, just moving from one storage type to another.

Higher Geography Hydrosphere

The Global Hydrological Cycle

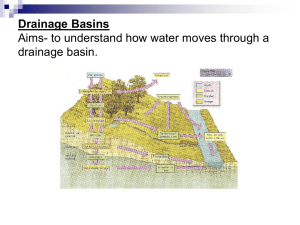

Drainage Basins

Study the diagram below of the hydrological cycle. Fill in the blank boxes using the words below. Use this worksheet to help you and ‘Higher Geography’, page 44-45. evaporation condensation Groundwater flow interception Surface run-off

Water vapour Throughflow precipitation Streamflow

Soil moisture evaporation

Run-out Ground-water storage

Higher Geography Hydrosphere Drainage Basins

The Drainage System Story

For this task, you need a piece of paper with a grid like this

For each statement draw a picture in the box like a cartoon strip.

1.

Precipitation falls (snow, rain, dew etc).

2.

Water is intercepted by vegetation.

3.

Evapotranspiration is when water is lost from the drainage basin to the atmosphere through plants.

4.

Water drips off leaves (throughfall), runs down tree trunks and stems

(stemflow).

5.

Water reaches the ground and is stored on the surface as puddles/in lakes/in reservoirs as surface storage.

6.

Water can be stored in a frozen state in glaciers, snow and ice.

7.

Water either moves horizontally across the surface as surface runoff towards the river OR infiltrates directly into the soil.

8.

If it infiltrates, it will be held as soil moisture storage.

9.

Water either moves horizontally through the soil as throughflow towards the river OR percolates vertically into the rocks below.

10.

If it percolates, it will be held as groundwater and slowly move towards the river as baseflow.

11.

Water moves down the river channel as streamflow (considered a store until it meets the sea/lake).

12.

Water is lost from a drainage basin through evaporation from surface storage or river discharge.

Decide whether each box represents an input, transfer, storage or output. Label you boxes accordingly – write it on or use a colour coding system.

Finally, add some essential colour to your pictures and add the key words to each box.

Higher Geography Hydrosphere

The Drainage System Story

Drainage Basins