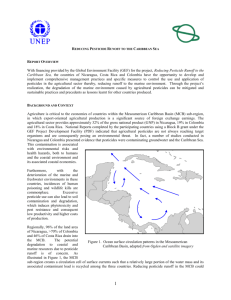

1-7-02 UNEP pesticides Caribbean project brief

advertisement