Waste incinerators - Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic

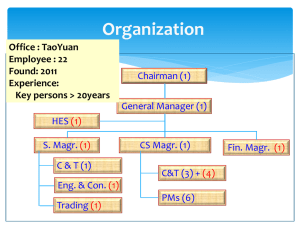

advertisement