Water and Wastewater Improvements in Urban

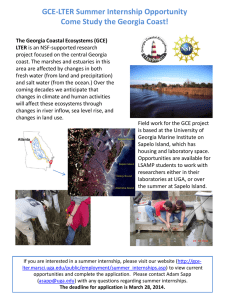

advertisement