Modernism

advertisement

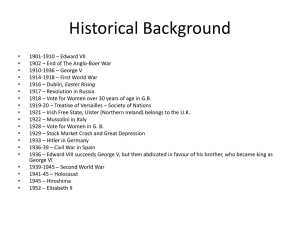

Modernism and Teaching Modern Literature Abstract: Modernism provides many of the major works that continue to define what literature and painting are. Understanding Modernism (between about 1870 and 1939) is essential for understanding modern literature. Can only gifted students understand Modernism? Can only gifted students understand modern literature and art? The focus here is on classics of prose, poetry and painting that are interesting in themselves and help to make sense of the period of cultural crisis that defined abstraction, fragmentation, pastiche, tricks of perspective and surrealism in modern literature and painting: T.S. Eliot The Waste Land (Part 1), W. B. Yeats ‘The Second Coming’, Gertrude Stein Picasso (selections) and paintings by Picasso and Dalí. Discussion includes the teaching advantages of the new iPad The Waste Land application and a range of easier novels. Modernism (about 1880 – 1939) is a cultural period defined in response to political revolution, international war, and world wide revolutionary changes in understanding the cosmos and human identity which encouraged a way of thinking in terms of a world, global perspective and a sense that the old world order was at an end: political events such as the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the extension of the right to vote to women (in Australia 1894-1908, in England 1918-21); scientific developments such as Einstein’s theory of relativity (1905-1917); industrial developments such as Ford’s mass production of the motor car (1913) and the rise of twentieth century global consumerism; medical developments such as Freud’s theory of psychosexual identity and psychoanalysis in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899); philosophical developments such as Nietzsche’s post-Christian theory of heroic existential survival in an abyss of modern disillusion and lack of traditional sanctions for values, as in Beyond Good and Evil (1886). The culture of Modernism is concerned with radical transformations of traditional high culture; the ‘new’ and the ‘modern’; liberation and optimism versus a sense of ending and catastrophe (with a focus on iconic events such as the sinking of the Titanic (1912), and the Battle of the Somme (1916) with more than a million casualties; focus on the city as a centre of utopian wealth and the abject uniformity and poverty of the masses (Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and Chaplin’s City Lights (1931)); celebration of class identity versus alienation and distrust of conformity; exploration of individual subjective identity and liberation from traditional rules, including sexual codes; tradition versus prophecies of the end of tradition and civilization – prophecies about the end of civilization are a major theme; celebration of high art and the artist versus mass culture, although with a direction towards mass culture becoming intellectual and aesthetic - as with Chaplin, the motor car, clothing fashion, illustrated magazines and advertising art, mass produced household goods and the modern home. Modernism and the Present: Modernism was interrupted, transformed and to some extent erased by the Second World War. The present period is closely linked with it and as well involves discontinuities and blanks in understanding. It makes sense to study Modernism in order to understand the present, but there are challenges. Modernism is one of the most popular and familiar forms of art in the contemporary world (think of the popularity of Picasso) but it can seem strange, alien and difficult. © Axel Kruse, English Dept, University of Sydney Page 1 Modernism and Teaching Modern Literature Some Implications for Teaching: The emphasis on high culture combined with the aesthetic and intellectual direction of mass culture involves challenges. (i) one reaction was to continue traditional forms; another was to destroy traditional art; another was to make art at once simple, strange and complex in a way that reflected their understanding of the critical condition of modernity. Modernism is often difficult and weird. It demands direct confrontation, including questions about the general nature of high art, and why this kind of high art is so complicated and who it is for. (ii) Study needs to include some of the more accessible range of the period – for example, a film such as City Lights; magazines and fashion such as the Saturday Evening Post and Norman Rockwell in 1925 (available online); and a popular novel or short story – Fitzgerald, Maugham? Modernism, Literature and Painting: A direction to formal aestheticism; abstraction, fragmentation, tricks of perspective and pastiche as with Picasso and cubism; cubism in painting parallels stream of consciousness, fragmentation, pastiche and dream-like tricks of perspective in literature as in The Waste Land; literature and the arts involve a strong focus, even an obsession, about civilization, the period and the world view; literature and painting involve mimesis of the perceived condition of the world as well as comment. In particular, the arts involve a tension between tradition and disruption in representation of the world, personal identity, and the sense of history and civilization; puzzles and dark prophecies are major directions in style and meaning. W. B. Yeats ‘The Second Coming’ (1921): The poetic voice and style are relatively direct and traditional, although in the manner of a prophetic puzzle. The first line sets a puzzle about what a ‘gyre’ is (it’s a conical shape), then the meaning is prophetic but more or less straightforward as a vision of the modern world as a state of catastrophic anarchy and loss of traditional values. In the second stanza the puzzle is that the Christian Second Coming of Christ at the end of the world is rewritten as an account of the present as the end of the old and the dawn of a new civilization where the new god is a ‘rough beast’ like a sphinx. Yeats said he associated the sphinx-like beast here with a new age of ‘laughing, ecstatic destruction’. There is also the minor puzzle of the Spiritus Mundi, as Yeats understood it, ‘the Great Memory’ of the world. The great strength of the poem is the reworking of a traditional poetic voice for Modernist prophecy and dreamlike images that Yeats derived from a personal code of magical vision (Freud, Jung, magic and late Romantic poetic vision combined). Yeats’s magical system is worth checking out to see the extremism of the possibilities for belief in the period. T. S. Eliot The Waste Land Part 1 (1922): In contrast to Yeats’s traditional poetic speech, the poetic voice here becomes a disjointed, fragmentary stream of consciousness performance which is a number of voices of characters (personas) who are representatives of the modern world. In the first verse paragraph: l.1-18 what seems at first to be the voice of the poet turns into a German speaking, European woman aristocrat talking about her past; l.19-42 shifts between four or so voices – a voice like a prophet of the horror of modernity, a quotation from Wagner in German, then a modern hyacinth girl (is she a flapper?), then perhaps her partner who has had a vision, then a return to Wagner. It is a dreamlike puzzle and operatic. The second verse paragraph is about Madame Sosostris a clairvoyant telling fortunes with a Tarot pack of cards – easy to understand and mainly sinister and satiric. The third verse paragraph seems to be the voice of the poet presenting a visionary, nightmarish account of the streets of London, © Axel Kruse, English Dept, University of Sydney Page 2 Modernism and Teaching Modern Literature as like a modern hell, a place of Gothic and Jacobean horror, with echoes of ancient Greece and Baudelaire that make modern London a site of western civilization in a state of urban confusion, decadence and ruin. For teaching: Read The Waste Land aloud first without explanation, and with different readers for each voice, act the voices, comment on how it is cinematic. Then check the reading experience without explanation and without footnotes or explanations of the literary references. For Eliot reading the poem see YouTube (he sounds very British for an American, and sombre in a way that does not register the mix of humour and horror in the poem). While the design is a fragmentary puzzle the meaning is more or less clear without close study and without the footnotes? The Waste Land is not difficult to understand as a prophetic account of the modern world as a sinister wasteland like a nightmare, a place of strange horror, a place where people live in a state of confusion and where the history of western civilization seems to be heading towards a barbaric end? What do the footnotes add? The poetry is accessible, part of the radical awareness of Modernism of being both in the modern world of mass culture (compare it to City Lights) and elitist in its learning and style. For close study see the iPad The Waste Land application. Picasso and Cubism 1906 – 1910: Show Picasso images from the cubist period including Picasso’s Portrait of Miss Gertrude Stein (1905 - 6) (online at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Portrait of Henry Kahnweiler (1910) (also online). Gertrude Stein If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso (1923). Recorded by Stein in New York, Winter 1934-35. For the recording see Pennsound Gertrude Stein: http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Stein.html Explore the similarities between the thoughtful abstraction of Picasso’s cubist portraits and Steins abstract ‘portrait’ of Picasso – extreme abstraction to the point of nonsense but with aesthetic design, wit and a sense of history; in one sense the end of the old world of civilization and art has happened with Picasso and Stein – the recording echoes Yeats’s theme of ‘laughing, ecstatic destruction’, and it sets a direction to later rap? Modernism at its most extreme is not so foreign in the contemporary world almost a hundred years later? Gertrude Stein Picasso (selections) (1938). This is less abstract but it is an exploration of writing in the manner of cubist abstraction in order to define Picasso and the period of Modernism. Read page 1: the characteristic Modernist concern with art as a definition of the times, with a bias to literary abstraction that is at once a kind of art for the sake of art, apparently artless and even child-like and primitive, wisdom that is contrary to ordinary ways of making sense of history and art, and a sophisticated game with contradiction and the absurd, and a kind of literary cubism. Read page 1 and note ‘everything changes’ then pages 7-8 on Stein’s portrait by Picasso. Read pages 9-12 and the claim that nothing changes except the things seen, and consider how this compares to other views of history. Read pages 29- 33 for a further post cubist version of the history of the world in the time of Modernism: ‘really nothing changes but at the same time everything changes’ (32). Modernism’s prophetic voice about momentous change continues here to a point immediately before the Second World War. © Axel Kruse, English Dept, University of Sydney Page 3