Rationale - Sylvia Knight

advertisement

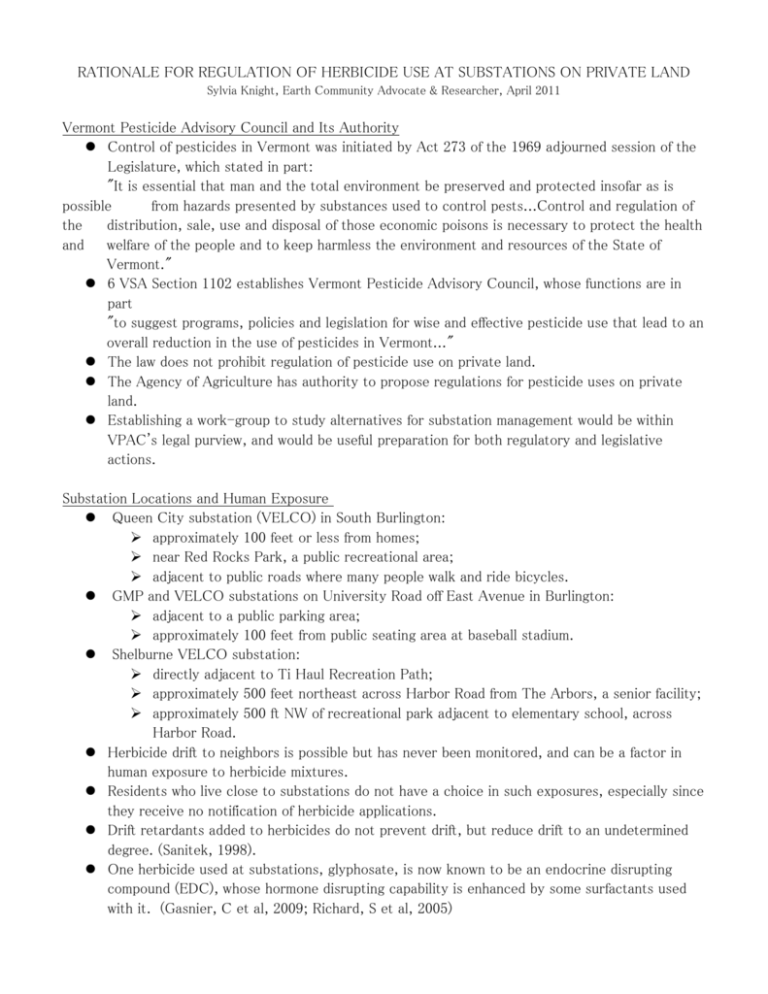

RATIONALE FOR REGULATION OF HERBICIDE USE AT SUBSTATIONS ON PRIVATE LAND Sylvia Knight, Earth Community Advocate & Researcher, April 2011 Vermont Pesticide Advisory Council and Its Authority Control of pesticides in Vermont was initiated by Act 273 of the 1969 adjourned session of the Legislature, which stated in part: "It is essential that man and the total environment be preserved and protected insofar as is possible from hazards presented by substances used to control pests...Control and regulation of the distribution, sale, use and disposal of those economic poisons is necessary to protect the health and welfare of the people and to keep harmless the environment and resources of the State of Vermont." 6 VSA Section 1102 establishes Vermont Pesticide Advisory Council, whose functions are in part "to suggest programs, policies and legislation for wise and effective pesticide use that lead to an overall reduction in the use of pesticides in Vermont..." The law does not prohibit regulation of pesticide use on private land. The Agency of Agriculture has authority to propose regulations for pesticide uses on private land. Establishing a work-group to study alternatives for substation management would be within VPAC's legal purview, and would be useful preparation for both regulatory and legislative actions. Substation Locations and Human Exposure Queen City substation (VELCO) in South Burlington: approximately 100 feet or less from homes; near Red Rocks Park, a public recreational area; adjacent to public roads where many people walk and ride bicycles. GMP and VELCO substations on University Road off East Avenue in Burlington: adjacent to a public parking area; approximately 100 feet from public seating area at baseball stadium. Shelburne VELCO substation: directly adjacent to Ti Haul Recreation Path; approximately 500 feet northeast across Harbor Road from The Arbors, a senior facility; approximately 500 ft NW of recreational park adjacent to elementary school, across Harbor Road. Herbicide drift to neighbors is possible but has never been monitored, and can be a factor in human exposure to herbicide mixtures. Residents who live close to substations do not have a choice in such exposures, especially since they receive no notification of herbicide applications. Drift retardants added to herbicides do not prevent drift, but reduce drift to an undetermined degree. (Sanitek, 1998). One herbicide used at substations, glyphosate, is now known to be an endocrine disrupting compound (EDC), whose hormone disrupting capability is enhanced by some surfactants used with it. (Gasnier, C et al, 2009; Richard, S et al, 2005) The Maximum Contaminant Level for glyphosate is 700 parts per billion. Glyphosate has been found to have endocrine disrupting effects at 500 ppb. (Gasnier, C et al, 2009) Children of pesticide applicators and farmers using glyphosate are at higher risk for ADD or ADHD. (Garry, VF et al, 2002) Children ages 2-15 are more vulnerable to pesticide exposures than adults. Specific types of cancers are increasing in children: leukemia, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, other tumor types, and the most deadly type of central nervous system tumors have increased yearly for the last 25 years. (Thayer, K and Houlihan, J, 2004) Substation Infrastructure, Herbicides, and Relation to Water Resources Substations are generally sterilized with pre-emergent, persistent herbicides. Substations at Blissville, Charlotte, Queen City (So. Burlington) and Shelburne (possibly others) are built with underground drainage systems to carry stormwater off-site to adjacent wetlands and nearby waters of the State. Shelburne substation drainage empties into the class 2 wetland adjacent to McCabe Brook, which connects with LaPlatte River at the south end of Shelburne Bay. Charlotte substation consumes a portion of wetland buffer and has an extended drain into the adjacent class 2 wetland contiguous with Pringle Brook, which connects with Lake Champlain. Queen City substation's underground drainage system extends toward Potash Brook (downhill), and is built upon sandy soil which enables leaching of contaminants toward the brook. Blissville substation is adjacent to a Class 2 wetland. Substations have a loose stone base to facilitate off-site movement of fluids (including herbicides), either into underground drainage systems or to surrounding areas during precipitation events. Given their loose stone base, drainage systems and herbicide treatments, substations can act as both point-source and non-point-source pollution to waters of the State. Protection of Water Resources 10 VSA Section 901 protects surface water resources: "It is hereby declared to be the policy of the state that the water resources of the state shall be protected... in the public interest and to promote the general welfare." 10 VSA Section 1390 (2,4-5) protects groundwater resources: "it is the policy of the state that the groundwater resources of the state shall be managed to minimize the risks of groundwater quality deterioration by regulating human activities that present risks to the use of groundwater ..." and "it is the policy of the state that the groundwater resources of the state are held in trust for the public." Clean Water Act requirements for NPDES permits for pesticide discharges to waters have been deferred until October 31, 2011. Drift retardants and surfactants present toxicity risks to aquatic life. (Haller, WT and Stocker, RK, 2003) USGS Toxic Substances Hydrology Program has sampled many mid-western streams for glyphosate and its degradation product AMPA. Glyphosate was found in 36% of samples, and AMPA was found in 69% of samples, both at low concentrations. (USGS, 2010) USGS worked with DuPont on a cooperative stream project and found sulfonylureas and imidazolinone herbicides in mid-western streams. (USGS, 2004) These herbicides can cause ecological damage at low concentrations. (Maciorowski AF, 1994) Adjuvants, Mixtures and Endocrine Disrupting Compounds (EDCs) Mixtures of herbicides have different toxicity than individual herbicides, and assessment of single pesticide toxicities can underestimate risk of pesticide mixtures. (Hayes T et al, 2006; Tatum V, 2011) Adjuvants can increase the toxicity or endocrine disruption effects of herbicides to humans. (Burroughs, B. et al, 1999; Gasnier, C et al, 2009) EDCs do not act according to the traditional toxicological principle that the concentration makes the poison; in fact, EDCs can interfere with hormonal systems in complex ways at extremely low concentrations, with long-lasting effects on wildlife and humans. (Norris, DO and Carr, JA, 2006; Krimsky, S 2000) Summing up Experience tells us that herbicides or pesticides used on one parcel of land move off-site to other areas including water, either through drift in air or runoff in water, and can adversely affect human and ecological health, as well as water resources protected by law for all. Substations are increasing in number and size, leading to more and more herbicide use. Costs deferred to communities from ongoing management with toxins can include the following: degraded water; degraded natural communities, and increased health care costs from exposure-related illnesses such as asthma, cancers, learning difficulties, thyroid problems, birth defects, nervous system degeneration, and increased incidents of chemical injury. VPAC was established to find ways to reduce such costs to society. Regulating herbicide use at substations will encourage utilities to take responsibility for financial as well as deferred costs of long-term use of toxins at their facilities. VPAC can further implement their lawful mandate to reduce pesticide use and to protect human and natural communities and the resources upon which they depend for life and health. REFERENCES Burroughs, B et al (1999). Herbicides and adjuvants: an evolving view. Toxicology and Industrial Health 15: 160-168. Gasnier, Celine et al (2009). Glyphosate-based herbicides are toxic and endocrine disruptors in human cell lines. Toxicology 262: 184-191. Haller, William T and Randall K. Stocker (2003). Toxicity of 19 adjuvants to juvenile Lepomis macrochirus (bluegill sunfish). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 22: 3: 615-619. Hayes, T et al (2006). Pesticide Mixtures, Endocrine Disruption, and Amphibian Declines: Are We Underestimating the Impact? Environmental Health Perspectives 114, Suppl. 1, April 2006 . http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/realfiles/members/2006/8051/8051.html Krimsky, Sheldon (2000). Hormonal Chaos: the Scientific and Social Origins of the Environmental Endocrine Hypothesis. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press). p. 123. Maciorowski, AF (1994). Qualitative assessment of sulfonylurea herbicides and other ALS inhibitors. Ecological Effects Branch, EPA. Norris, David O. and James A. Carr, eds. Endocrine Disruption: Biological Bases for Health Effects in Wildlife and Humans. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006) Preface, vii. Richard, Sophie et al (2005). Differential effects of glyphosate and Roundup on human placental cells and aromatase. Environmental Health Perspectives. Online 24 February 2005. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Available online at http://dx.doi.org. Use doi: 10.1289/ehp.7728 Sanitek Products, Inc. (1998). Label for 38-F drift retardant. Tatum, Vickie et al (2011). Acute toxicity of commonly used forestry herbicide mixtures to Ceriodaphnia dubia and Pimephales promelas. Environmental Toxicology 26. DOI: 10.1002/tox.20686 Thayer, Kristina and Jane Houlihan (2004). Pesticides, Human Health and the Food Quality Protection Act. William & Mary Environmental Law & Policy Review 28: 257-312 US Geological Survey (2010). Glyphosate herbicide found in many mid-western streams... http: //toxics.usgs.gov/highlights/glyphosate02.html US Geological Survey (2004). Sulfonylurea, Sulfonamide, Imidazolinone, and Other Pesticides. http://co.water.usgs.gov/midconherb/html/sulfonylurea.html