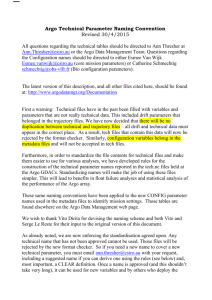

Revised document - School of GeoSciences

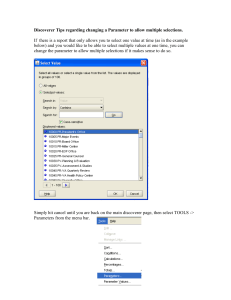

advertisement