Hypothesis Testing

advertisement

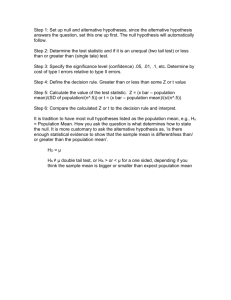

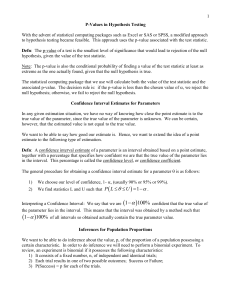

Chapters 8, 9 – Introduction to Statistical Inferences, One Population There are two branches of statistical inference, 1) estimation of parameters and 2) testing hypotheses about the values of parameters. We will consider estimation first. Defn: A point estimate of a parameter (a numerical characteristics of a population) is a specific numerical value based on the data obtained from a sample. To obtain a point estimate of a parameter, we summarize the information contained in the sample data by using a statistic. A particular statistic used to provide a point estimate of a parameter is called an estimator. Characteristics of an Estimator To provide good estimation, an estimator should have the following characteristics: 1) The estimator should be unbiased. In other words, the expectation, or mean, of the sampling distribution of the estimator for samples of a given size should be equal to the parameter which the statistic is estimating. 2) The estimator should be consistent. In other words, if we increase the size of the sample which we select from the population, the estimator should yield a value which gets closer to the true value of the parameter being estimated. 3) The estimator should be relatively efficient. In other words, of all possible statistics that could be used to estimate a particular parameter, we want to choose the statistic whose sampling distribution has the smallest variance. It turns out that, for a population mean, , the sample mean, X , is an estimator which is unbiased, consistent, and relatively efficient. In any given situation, we have no way of knowing precisely how close the estimated value of a parameter is to the true value of the parameter. However, if the estimator satisfies the three properties listed above, we can be highly confident that the estimated parameter value is unlikely to differ from the true parameter value by much. On the other hand, it is nearly certain that the estimated value will not be exactly equal to the true parameter value. We want to have some idea of the precision of the estimate. Hence, rather than simply calculating a point estimate of the parameter value, we find a confidence interval estimate. Defn: A confidence interval estimate of a parameter consists of an interval of numbers obtained from a point estimate of the parameter, together with a percentage that specifies how confident we are that the true parameter value lies in the interval. This percentage is called the confidence level, or confidence coefficient. Thus, there are three quantities that must be specified: 1) the point estimate of the parameter, 2) the width of the interval (which is usually centered at the value of the point estimate), and 3) the confidence level. Confidence Interval for a Population Mean (Assuming that the population standard deviation is known): If we are sampling from a population which has a normal distribution, or if our sample size is large enough (n 30), then we may find the confidence interval as follows (we will talk about the more realistic situation in which the population standard deviation is unknown later). We know that, in either of the situations (normality or large sample size), the random variable X X has either a standard normal probability distribution (in the first case) or an approximate Z X n standard normal probability distribution (in the second case). Hence, for a given percentage , we may make the following probability statement: X X P z z 1 . X 2 2 n We can rearrange the quantities in parentheses to obtain an equivalent probability statement by multiplying throughout the inequality by the quantity X . We obtain n P z X X z X 1 . n 2 2 n We want to isolate the parameter, , in the middle of the inequality, so we subtract X throughout, obtaining P X z X X z X 1 . n n 2 2 We are almost done. We do not want - in the center, but rather , so we multiply throughout by –1, obtaining P X z X X z X 1 . n n 2 2 Then the endpoints of our confidence interval are X z 2 X n and X z 2 X n . The confidence level is 1 - . Intervals constructed in the above manner are called confidence intervals for the corresponding parameter (in this case, a population mean, ). We are usually interested in one of several specific values of the confidence level, either 90%, or 95% or 99%. 1) For 1 - = .90, we have z 0.05 1.645 , and the 90% confidence interval for has the form X 1.645 X , X 1.645 X . n n 2) For 1 - = .95, we have z 0.025 1.96 , and the 95% confidence interval for has the form X 1.96 X , X 1.96 X . n n 3) For 1 - = .99, we have z 0.005 2.575 , and the 99% confidence interval for has the form X 2.575 X , n X 2.575 X . n We interpret a confidence interval as follows. A confidence interval with confidence level (1 )100% is an interval obtained from sample data by a method such that, (1 - )100% of all intervals obtained by this method would, in fact, contain the true value of the parameter, and 100% of all intervals so obtained would not contain the true value of the parameter. (See page 291 of the textbook) Example: p. 320, Exercise 8.26. Estimation of Population Means, When Is Unknown If we know the population standard deviation, , then we can use the previous formula for finding a confidence interval for the population mean, . However, in nearly every practical situation, we know neither. We then must use the sample standard deviation, S, as an estimate of the population standard deviation, and the previous formula for the confidence interval for is no longer valid. Instead of using the standard normal distribution for constructing the confidence interval, we use a related distribution, called the t distribution. Characteristics of the t Distribution: 1) It is bell-shaped. 2) The distribution is unimodal (one peak) and symmetric, and the mean, median and mode are all equal to 0. 3) The curve is continuous; i.e., there are no gaps. 4) The total area under the curve is 1. 5) The curve extends indefinitely in both directions, approaching, but never touching, the horizontal axis. 6) The variance is greater than 1. 7) There is actually a family of t-distributions, each one characterized by a parameter called the degrees of freedom. 8) The t-curve is wider than the standard normal curve, but for larger sample sizes, the t-curve is closer to the standard normal curve. (See the graph on page 298 of your textbook for examples of t-curves.) Note: The symbol d.f. will be used for degrees of freedom. The concept denotes the number of values in the data set which are free to vary. When we first select a random sample of size n, we have n degrees of freedom. After we compute the sample mean, we have used up one degree of freedom, and now d.f. = n – 1. If we compute a second statistic from the data, then we use up another degree of freedom, and now d.f. = n – 2. Formula for a Confidence Interval for When is Unknown, and n < 30: We modify our previous formula somewhat. When the population standard deviation is unknown, the S S . Here S is , X t (1 – )100% confidence interval for the mean is given by: X t , n 1 , n 1 n n 2 2 the sample standard deviation, and t 2 , n 1 is the called a critical value for the t distribution with d.f. = n – 1. We can find t critical values using Table F in Appendix C if we know the degrees of freedom of the t-distribution and the confidence level, 1- . For this purpose we would use the two-tail values for . For example, if our confidence level is (1 - )100% = 95%, then = 0.05. If our sample size is 25 then d.f. = 24, and the t-critical value is 2.064. Finding a Confidence Interval for Using the TI-83 Calculator: Given a data set of n sample values X1, X2, … , Xn, where these represent a random sample from a population with unknown mean , we can find a (1 – )100% confidence interval for as follows: 1) Enter the data in the calculator, using STAT and 1:Edit. 2) Choose STAT, then TESTS, then 8:T Interval. 3) Choose Data by hitting ENTER; or if the sample mean and sample standard deviation are given to you, choose Stats. 4) If we don’t know the sample mean and sample standard deviation, then we would choose Data, enter the variable name for List:, and enter the appropriate confidence level. If we know the sample mean and the sample standard deviation, then we would choose Stats, rather than Data, and enter the value of the sample mean, the value of the sample standard deviation, the sample size, and the appropriate confidence level. 5) Hit ENTER. Example: p. 383, Exercise 9.29. Estimation of Population Proportions Sometimes we want to use sample data to estimate the proportion, p, of a population that have a certain characteristic. The point estimate of p would be the proportion, p̂ , that have the characteristic of interest. In this case, we are talking about using a binomial experiment to do the estimation. We would select a random sample of n members of the population; the randomness insures that the n trials are independent of each other. We are seeking the same information about each sample member, whether the member has the characteristic of interest. Thus the trials are identical. Each trial results in one of two possible outcomes; either the member has the characteristic, or the member does not have the characteristic. Assuming that the sample is random, the probability that a member has the characteristic is p, the proportion of the population who have the characteristic. Hence the three conditions of a binomial experiment are satisfied. If we define X = number of members of the sample who have the characteristic, then X has a binomial distribution with parameters n and p. X . If the sample size n is large enough, then this random variable has an approximate normal distribution, and the random pˆ p variable has an approximate standard normal distribution. We can construct a (1 – pˆ (1 pˆ ) n )100% confidence interval for p using this fact. The form of the confidence interval is The proportion of the sample who have the characteristic of interest is then pˆ pˆ 1 pˆ pˆ 1 pˆ pˆ z . To find z , we look in the table of the standard normal ˆ z , p n n 2 2 2 distribution, Table E in Appendix C. If our confidence level is (1 - )100% = 95%, then = 0.05, and we divide this by two and substract from 0.5, to get 0.4750. Looking in the table, we find that the critical value corresponding to the probability 0.4750 is 1.96. Finding a Confidence Interval for p Using the TI-83 Calculator: Given the number n of trials in our binomial experiment (size of sample) and the number of successes (number of members of the sample with the characteristic of interest), where the sample was taken from a population in which the unknown proportion of members with the characteristic is p, we can find a (1 – )100% confidence interval for p as follows: 1) Enter the data in the calculator, using STAT and 1:Edit. 2) Choose STAT, then TESTS, then A:1-PropZInt. 3) Enter the value of X, the sample size, and the appropriate confidence level. 5) Hit ENTER. Example: p. 397, Exercise 9.62. Hypothesis Testing The other branch of statistical inference is concerned with testing hypotheses about the value of parameters. Defn: A hypothesis is a statement about the value of a population parameter. Defn: In a hypothesis test, the hypothesis which the researcher is attempting to prove is called the alternative (or research) hypothesis, denoted Ha. The negation of the alternative hypothesis is called the null hypothesis, H0. The null hypothesis usually represents current belief about the value of the parameter. The researcher suspects that the null hypothesis is false, and wants to disprove it. Note: Hypotheses are tested in pairs (here the symbol 0 represents some specified number): If the null hypothesis is H0: = 0, then the corresponding alternative hypothesis is Ha: 0. If the null hypothesis is H0: 0, then the corresponding alternative hypothesis is Ha: < 0. If the null hypothesis is H0: 0 , then the corresponding alternative hypothesis is Ha: > 0. In each case, the alternative hypothesis is a strict inequality; the null hypothesis is not. The above hypothesis statements are written in terms of a population mean, . If we are testing hypotheses about a population proportion, p, or some other parameter, that parameter would appear instead of . Example: If the researcher wants to prove that the proportion, p, of the U.S. population who catch a cold between October 1 and March 31 is more than 40%, the two hypotheses would be stated as follows: H0: p 0.40 Ha: p > 0.40 Example: If the researcher is in charge of quality control for the Pepsi-Cola Company, and wants to determine whether an assembly line at a plant which produces 12-oz. cans of Pepsi is working properly, the hypotheses would be stated as follows in terms of the mean amount of Pepsi in the cans: H0: = 12 oz. Ha: 12 oz. Note: We cannot prove the null hypothesis; we may disprove it, or we may fail to disprove it. After taking a sample and conducting a test, we will either reject H0 and believe Ha, or we will fail to reject H0 because of insufficient evidence against it. There are four possibilities: 1) We reject the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is, in fact, true. In this case, we make a Type I Error. 2) We reject the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is, in fact, false. In this case, we make a correct decision. 3) We fail to reject the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is, in fact, true. In this case, we make a correct decision. 4) We fail to reject the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is, in fact, false. In this case, we make a Type II Error. We want to maximize the probability of making a correct decision, and minimize the probability of making either a Type I Error or a Type II Error. We use the following notation: P(Type I Error) = P(Reject H0 | H0 True) = . P(Type II Error) = P(Fail to Reject H0 | Ha True) = We want both of these probabilities to be as small as possible. However, if we choose the value of to be smaller, the value of will automatically become larger. To see this, consider the analogy of the American criminal justice system. Suppose that you are the defendant in a murder trial. The hypotheses are H0: Defendant innocent vs. Ha: Defendant guilty The prosecutor is attempting to disprove the null hypothesis, thus proving the alternative hypothesis. To do this, the prosecutor presents evidence to the jury. The jury makes a decision on the basis of the evidence. The jury can decide to reject the null hypothesis, or to fail to reject the null hypothesis. In either case, the jury cannot know with absolute certainty that the decision is correct. If the rules of evidence are changed to make it more difficult for the jury to convict (reject H0), then it becomes easier for the jury to acquit (fail to reject H0). Then it less likely that the jury will make a Type I Error, but more likely that the jury will make a Type II Error. Thus, has been made smaller, but becomes larger. If the rules of evidence are changed to make it easier for the jury to convict (reject H0), then it becomes more difficult for the jury to acquit (fail to reject H0). Then it more likely that the jury will make a Type I Error, but less likely that the jury will make a Type II Error. Thus, has been made larger, but becomes smaller. The only way that we can reduce both and at the same time (make erroneous decisions less likely) is to gather more evidence. In statistical hypothesis testing, “gather more evidence” means choose a larger sample from the population (choose a larger value of n). We also begin our hypothesis test by choosing a value for , based on our assessment of the relative consequences of making a Type I Error, vs. the consequences of making a Type II Error. If we believe that the consequences of making a Type I Error are more serious than the consequences of making a Type II Error, we want to choose to be rather small, perhaps 0.01 or 0.001. If we believe that the consequences of making a Type II Error are more serious than the consequences of making a Type I Error, we want to choose to be rather large, perhaps 0.10. The most common choice for is 0.05. The evidence from the sample is used in the form of the value of a test statistic. Defn: The test statistic is a random variable whose value depends on the sample data, such that the value of the statistic tells us whether to reject H0 or to fail to reject H0. We must choose the test statistic so that we know its sampling distribution under H0. Defn: The rejection region is the set of possible values of the test statistic which would lead us to reject H0 and assert that we have proved Ha. Defn: The significance level of the test is the probability, , of making a Type I Error. Defn: The p-value of the test is the probability (under H0) of obtaining a value of the test statistic at least as extreme as the one which is actually obtained from the data. Note: To make our decision, we compare the computed p-value, obtained from the calculator, with our chosen value of . If the p-value is smaller than , we reject H0 and say that we have proved Ha. If the p-value is larger than our chosen value of , then we fail to reject H0. Types of Alternative Hypotheses: One-Tailed Tests or Two-Tailed Tests There are three forms for an alternative hypothesis: 1) Ha: 0 2) Ha: < 0 3) Ha: > 0 The first form results in a two-tailed test, so called because the rejection region consists of two intervals, one associated with the left-hand tail of the probability distribution of the test statistic, and the other associated with the right-hand tail of the distribution. The second form results in a one-tailed test, because the rejection region is an interval associated with the left-hand tail of the probability distribution of the test statistic. The third form results in a one-tailed test, because the rejection region is an interval associated with the right-hand tail of the probability distribution of the test statistic. Steps in Hypothesis Testing Step 1: State the alternative hypothesis, Ha. (This is what we are trying to prove; it must be a strict inequality. Making this statement will involve translating the research conjecture into a statement involving the parameter.) State the null hypothesis, H0. (This is what we are trying to disprove; it cannot be a strict inequality. This statement will be the negation of the alternative hypothesis.) Step 2: Choose the size of the random sample(s) to be selected from the population(s). Choose the significance level, , for the test. In this course, you will usually be given this number, and the most common value is 0.05. In a real research situation, the researcher would choose the value based on an assessment of the relative seriousness of the consequences of making a Type I Error vs. a Type II Error. Step 3: Choose the test statistic which will be used. In this course, if the hypotheses concern one or more population means, the test statistic will be a t-statistic. If the hypotheses concern a population proportion, the test statistic will be a Zstatistic. Step 4: Choose the random sample(s) and collect the data. Compute the value of the test statistic, and the associated p-value. We will do this using the TI-83 calculator. Step 5: Make a decision based on a comparison of the p-value associated with the test statistic with the chosen level of significance. If p-value < , we reject H0 and affirm Ha. Otherwise, we fail to reject H0. Step 6: State the conclusion of the hypothesis test. If we reject the null hypothesis, the conclusion should have the following form: “We reject H0 at the () level of significance. We have sufficient evidence to conclude (statement of research conjecture).” If we fail to reject the null hypothesis, the conclusion should have the following form: “We fail to reject H0 at the () level of significance. We do not have sufficient evidence to conclude (statement of research conjecture).” Example: Suppose a consumer protection agency has received complaints that 24-oz. packages of Post Grape-Nuts contain less than 24 oz. of product. The agency wants to test this claim. They select a random sample of 100 boxes of cereal and measure the amount of product in each one. The sample average is X = 23.94 oz., and the sample standard deviation is S = 0.13 oz. Test the claim at the 0.05 level of significance. Step 1: H0: 24 oz. Ha: < 24 oz. Step 2: n = 100, = 0.05 Step 3: The test statistic will be t X 24 oz. . Under the null hypothesis, this statistic has a t S n distribution with d.f. = 99. Step 4: We choose our random sample of 100 boxes, weigh the contents of each one. We obtain X = 23.94 oz., and S = 0.13 oz. Using the TI-83, choose STAT, then TESTS, then 2:T-Test. Choose Stats, rather than Data, since in this case we know the sample mean and sample standard deviation. Input the value of 0 appearing in the null hypothesis, in this case, 24. Input the sample mean and the sample standard deviation, and the sample size. Also, we must tell the calculator which of the three forms of alternative hypothesis we are using. In this case, we are using the second form. Choose Calculate. Step 5: The value of the test statistic is –4.6154. The p-value associated with this test is 0.00000589. This is less than , so we reject the null hypothesis. Step 6: We reject H0 at the 0.05 level of significance. We have sufficient evidence to conclude that the average amount of Grape Nuts in a 24-oz. box is less than 24 oz. Example: p. 385, Exercise 9.42. Example: p. 385, Exercise 9.43. Tests of Hypotheses Concerning Population Proportions The types of alternative hypotheses are as follows: Ha: p p0 Ha: p < po Ha: p > po In order to conduct a test of hypotheses about the value of a population proportion, we must do a binomial experiment. We will choose a random sample of n members of the population; this will guarantee that the n trials in our experiment are independent of each other. For each member of the population we want to know the same information – does this member have the characteristic of interest; hence the n trials are also identical. For each trial, the information sought is in the form of a yes-or-no question – does the member have the characteristic of interest; hence there are only two possible outcomes for each trial. Finally, since we are randomly sampling from the population, the probability that any one member of the sample will have the characteristic of interest is simply the proportion, p, of the entire population who have the characteristic of interest. Hence the probability of success is the same for each trial, namely p. From the Central Limit Theorem, if our sample size is large enough, then the following random pˆ p variable has an approximate standard normal distribution: Z . The normal p(1 p) n approximation will be reasonable if n > 20, and np > 5 and n(1-p) > 5. In the formula above p̂ is the proportion of the sample who have the characteristic of interest. Under the null hypothesis, this random variable is a statistic, Z pˆ p 0 p 0 (1 p 0 ) n . This will be the test statistic for our hypothesis test. The hypothesis test will have the same steps as those used for testing hypotheses about population means: Step 1: We state the null and alternative hypotheses. Step 2: We state our chosen sample size and significance level. Step 3: We state the form of the test statistic and its probability distribution under the null hypothesis. Step 4: We choose our random sample, do our measurements, and compute the value of the test statistic and the associated p-value. Step 5: We compare the p-value to make a decision. Step 6: We state our conclusion, in terms of the statement we were trying to prove, and including the level of significance of the test. Example: The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration conducts surveys on drug use by type of drug and age group. Results are published in National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. According to that publication, 12.0% of 18-25 year-olds were current users of marijuana or hashish in 1995. A recent poll of 1283 randomly selected 18-25 year-olds revealed that 146 of them currently use marijuana or hashish. At the 10% significance level, do the data provide sufficient evidence to conclude that the percentage of 18-25 year-olds who currently use marijuana or hashish has changed from the 1995 percentage of 12.0%? Step 1: H0: p = 0.12 Ha: p 0.12 Step 2: n = 1283 and = 0.10 Step 3: The test statistic is Z pˆ 0.12 (0.12)(0.88) 1283 , which under the null hypothesis has an approximate standard normal distribution. Step 4: X = 146. We choose STAT, TESTS, 1-PropZTest. We enter the null-hypothesized value, 0.12, the value of X, and the sample size. We tell the calculator which of the three alternatives we are using. We find z = -0.683861, and p-value = 0.4940628. Step 5: p-value > . We don’t reject the null hypothesis. Step 6: We fail to reject H0 at the 0.10 level of significance. We do not have sufficient evidence to conclude that the proportion of 18-25 year-olds currently using marijuana or hashish differs from the proportion found in 1995. Example: p. 401, Exercise 9.83. Example: p. 401, Exercise 9.85.