Metal Ion Complexes Stability in Aqueous Solutions

advertisement

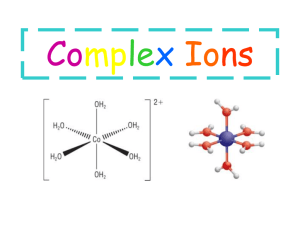

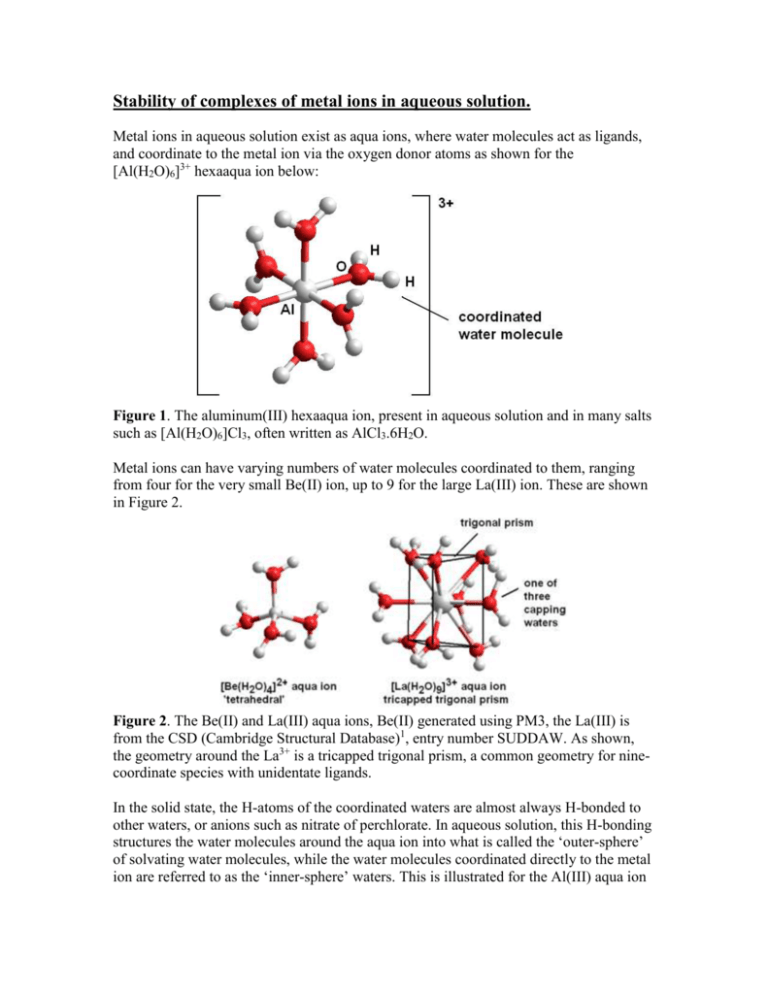

Stability of complexes of metal ions in aqueous solution. Metal ions in aqueous solution exist as aqua ions, where water molecules act as ligands, and coordinate to the metal ion via the oxygen donor atoms as shown for the [Al(H2O)6]3+ hexaaqua ion below: Figure 1. The aluminum(III) hexaaqua ion, present in aqueous solution and in many salts such as [Al(H2O)6]Cl3, often written as AlCl3.6H2O. Metal ions can have varying numbers of water molecules coordinated to them, ranging from four for the very small Be(II) ion, up to 9 for the large La(III) ion. These are shown in Figure 2. Figure 2. The Be(II) and La(III) aqua ions, Be(II) generated using PM3, the La(III) is from the CSD (Cambridge Structural Database)1, entry number SUDDAW. As shown, the geometry around the La3+ is a tricapped trigonal prism, a common geometry for ninecoordinate species with unidentate ligands. In the solid state, the H-atoms of the coordinated waters are almost always H-bonded to other waters, or anions such as nitrate of perchlorate. In aqueous solution, this H-bonding structures the water molecules around the aqua ion into what is called the ‘outer-sphere’ of solvating water molecules, while the water molecules coordinated directly to the metal ion are referred to as the ‘inner-sphere’ waters. This is illustrated for the Al(III) aqua ion below, where each H-atom from an inner-sphere water has a water molecule H-bonded to it, giving twelve water molecules in the outer-sphere: Figure 3. The Al(III) aqua ion showing the six inner-sphere waters (colored green) and twelve outer-sphere waters H-bonded to the inner-sphere. A point of interest is that water can exist also as a bridging ligand, as in numerous complexes such as those shown below: Figure 4. Bridging waters as found in a) the [Li2(H2O)6]2+ cation (CSD = CELGUV) and b) the [Na2(H2O)10]2+ cation (CSD = ECEPIL). Metal aquo ions can act as Brønsted acids, which means that they can act as proton donors. Thus, an aqua ion such as [Fe(H2O)6]3+ is a fairly strong acid, and has2 a pKa of 2.2. This means that the equilibrium constant for the following equilibrium has a value of 102.2. [Fe(H2O)6]3+(aq) [Fe(H2O)5OH]2+(aq) + H+(aq) [1] Thus, if one dissolves a ferric salt, such as FeCl3.6H2O in water, a fairly acidic solution of pH about 2 will result. In fact, the orange color of such solutions is due to the presence of the [Fe(H2O)5OH]2+ ion, and the [Fe(H2O)6]3+ cation is actually a very pale lilac color. The latter color can be seen in salts such as Fe(NO3)3.9 H2O, which contains the [Fe(H2O)6]3+ cation. Metal aqua ions display varying pKa values that are dependent on size, charge, and electronegativity. 1) The smaller the metal ion, the more acidic it will be. Thus, we have for the group 2 metal ions the following pKa values (note that ionic radii3 increase down a group): Metal ion: Be2+ Mg2+ Ca2+ Sr2+ Ba2+ Ionic radius (Å): pKa: 0.27 5.6 0.74 11.4 1.00 12.7 1.18 13.2 1.36 13.4 2) The higher the charge on metal ions of about the same size, the more acidic will the metal ion be: Metal ion: Na+ Ca2+ La3+ Th4+ Ionic radius (Å): pKa: 1.02 14.1 1.00 12.7 1.03 8.5 0.94 3.2 3) Electronegativity. The closer a metal is to Au in the periodic table, the higher will its electronegativity be. Electronegativity tends to override the first two factors in controlling the acidity of metal aqua ions, and metal ions of higher electronegativity will be much more acidic than metal ions of similar size and charge of low electronegativity. Electronegativities of the Elements Figure 5. Electronegativities of the elements. Thus, one sees that Pb2+ will have a high electronegativity of 1.9, while the similarly sized and charged Sr2+ will have a low electronegativity, and consequently much lower acidity. Similar results are observed for the pairs of metal ions Na+ and Ag+, Y3+ and Tl3+, and Ca2+ and Hg2+ (these results can be rationalized by referring to the above periodic table in Figure 5): Metal ion: Sr2+ Pb2+ Na+ Ag+ Ionic radius (Å): pKa: 1.19 13.2 1.18 8.0 1.02 14.1 1.15 12.00 Metal ion: Y3+ Tl3+ Ca2+ Hg2+ Ionic radius (Å): pKa: 0.90 7.7 0.89 0.6 1.00 12.7 1.02 3.4 One finds that metal ions are 50% hydrolyzed at the pH that corresponds to their pKa. This can be summarized as a species distribution diagram as shown below: Figure 6. Species distribution diagram for Cu(II) in aqueous solution. Other solution species such as [Cu(OH)2]2+ have been ignored in calculating the diagram. Note that the concentrations of Cu2+ and Cu(OH)+ are equal at a pH equal to the pKa of 6.5. Solubilities of metal hydroxides. If one leaves an orange solution of a ferric salt to stand, after a while it will clear, and an orange precipitate of Fe(OH)3(s) will form. The extent to which Fe3+ can exist in solution as a function of pH can be calculated from the solubility product, Kso. For Fe(OH)3, the expression for Kso is given by: Kso = [Fe3+] [OH-]3 = 10-39 [2] One thus finds that the maximum concentration of Fe3+ in solution is controlled by pH. Note that we need [OH-] in expression 2, which is obtained from the pH from equation 3. pKw = pH + pOH = 14 [3] Thus, if the pH is 2, then pOH = 12, and so on. pOH is related to [OH-] in the same way as pH is related to [H+]. pH = -log [H+] [4] pOH = -log [OH-] [5] We can thus calculate the maximum concentration of [Fe3+] as a function of pH from equation 2. maximum molarity Fe3+ as a function of pH 5 0 -5 0 5 10 15 log [Fe3+] -10 -15 -20 Series1 -25 -30 -35 -40 -45 pH Figure 7. Variation of log [Fe3+] as a function of pH, calculated from equation 2. It is assumed that the maximum [Fe3+] placed in solution is 1.0 M. It is found that Kso is, like pKa for aqua ions, a function of metal ion size, charge, and electronegativity. Thus, Fe3+ is a small ion of fairly high charge, and not-too-low electronegativity, and so forms a hydroxide of low solubility. Thus, the hydroxide of Na+, which is NaOH, is highly soluble in water, while at the other extreme, Pu(OH)4(s) is of very low solubility (Kso = 10-62.5). The latter fact is fortunate, because the highly radioactive Pu(IV) is not readily transported in water, since it exists as a precipitated hydroxide. Note that for solubility products, the number of hydroxides must balance the charge on the metal ion, and the expression for Kso contains the hydroxide concentration raised to the power of the number of hydroxides in the solid. Thus for metal ions of different charges we have: For Al(OH)3(s), Kso = 10-33.7 = [Al3+] [OH-]3, but for Pb(OH)2(s), Kso = 10-14.9 = [Pb2+][OH-]2, and for AgOH (s), we have Kso = [Ag+] [OH-] = 10-7.7. Metal oxides and hydroxides. Metal oxides can be regarded simply as dehydrated hydroxides. Metal hydroxides can usually be heated to give the oxides, although sometimes very high temperatures are required: 2 Al(OH)3(s) = Al2O3(s) + 3 H2O(g) [6] The formation of ceramics involves such firing of hydrated metal salts in a kiln, with waters of hydration being driven off. The oxides tend to be less soluble than the freshly precipitated hydroxides, and on standing many hydroxides lose water, and ‘age’. Thus, aged precipitates of hydroxides can be much less soluble than freshly precipitated hydroxides. Fresh ‘CaO’ is quite water soluble, but old samples can be highly insoluble. Amphoteric behavior. When one looks at the periodic table, one finds that at the very left, metal oxides are basic. That means that if they are dissolved in water, they give basic solutions: Na2O (s) + H2O (l) 2 Na+ (aq) + 2 OH- (aq) = [7] On the right hand side, metal oxides dissolve to give acidic solutions, as with sulfur trioxide: SO3(s) + H2O (l) 2H+ (aq) = + SO42- (aq) [8] There is a transitional area where the metals can display both basic and acidic behavior. This is called amphoteric benhavior. Thus, Al(III) can display both acidic properties and basic properties: Acidic: [Al(H2O)6]3+ Basic: [Al(OH)4]- [Al(H2O)5(OH)]+(aq) [Al(OH)3] (aq) + + H+ (aq) OH- (aq) [9] [10] At low pH Al(III) is acidic, while at high pH it is basic. The range of existence of the species [Al3+], [Al(OH)2+], and [Al(OH)4-] is shown in the species distribution diagram below: Al(III) species distribution 100 % of Al as species shown 90 80 70 60 Al3+ Al(OH)2+ [Al(OH)4]- Series1 Series2 Series3 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 5 10 15 pH Figure 8. Species distribution diagram for Al(III) showing the distribution of [Al3+], [Al(OH)2+], and [Al(OH)4-] as a function of pH. Metal ions that are amphoteric in the periodic table are highlighted in red below: Be(II) B(III) C N O F Mg(II) Al(III) Si P S Cl Zn(II) Ga(III) Ge As Se Br Cd(II) In(III) Sn (II) Sb Te I Hg(II) Tl(III) Pb(II) Bi(III) Po The species formed at high pH are, for example, the tetrahedral ions [Be(OH)4]2-, [Zn(OH)4]2-, [Al(OH)4]-, and [Ga(OH)4]-. Ligands. A ligand is a molecule or ion that has a donor atom that can donate a pair of electrons to a metal ion to form what is called a complex. Thus, in the complex [Co(NH3)5Cl]Cl2, the NH3 and Cl- (only the one inside the brackets) are ligands. In NH3, the N is the donor atom. The two chlorides outside the brackets are not acting as ligands here, since they are not bonded to the Co. The [Co(NH3)5Cl]2+ is a complex cation, and the two Cl- ions outside the brackets are only counter-ions. Some examples of ligands are: Monodentate ligands (only one donor atom): Neutral: NH3, H2O, P(C6H5)3, CO, C6H5N (pyridine), C4H8O (THF, tetrahydrofuran) Anionic: OH-, CN-, F-, Cl-, Br-, I-, CH3COO- (acetate), SCN- (thiocyanate). Bidentate chelate ligands O H2N NH 2 ethylene diamine (en) - O O- O oxalate (ox) N N N 2,2'-bipyridyl (bipy) N 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) Tridentate chelate ligands O H2N N H NH 2 diethylene triamine (dien) - O O N H O- iminodiacetate (IDA) N N terpyridyl (terpy) N Tetradentate chelate ligands O H2N N H N H O - NH 2 O triethylene tetramine (trien) N H O- N H ethylenediaminediacetate (EDDA) Hexa- and octa-dentate chelate ligands O - O O - N O- N O- O O O EDTA ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid O - O O N N - O- N O- O- O O O O DTPA diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid Some views of complexes of polydentate chelating ligands are shown in Figure 9. Figure 9. Views of the complexes a) [Ca(EDTA)(H2O)2]2- and b) [Co(en)3]3+. Formation constants. The formation constant for a complex ML formed between a metal ion M and a ligand L is given by (square brackets indicate molarity): K = [ML] / [M] [L] [11] We have already discussed OH-, which is a ligand. The pKa for a metal ion is related to its log K1(OH-) value by: pKw = pKa + log K1(OH-) [12] Thus, with pKw = 14.0, if we have pKa for Fe3+(aq), then log K1(OH-) for Fe3+ is 14.0 – 2.2 = 11.8. Note that because K1 values are usually quite large, they are normally expressed as logarithms, i.e. log K1. The subscript ‘1’ denotes that one ligand has been added to form a complex ML. Formation constants that refer to the addition of more than one ligand can be stepwise, or cumulative. Stepwise constants are indicated by log Kn values, where n can have values 1,2,3,….. The cumulative constants are indicated by β values, such that βn = K1 x K2 x K3 x.. Kn, or log βn = log K1 + log K2 + log K3 +.. log Kn. This is illustrated by the log Kn and log βn values for the Ni(II)/ammonia system. (Note: Waters coordinated to the Ni(II) as in e.g. [Ni(H2O)6]2+ have been left off for simplicity. Equilibrium n log Kn log βn Ni2+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)2+ 1 2.73 2.73 (= log K1) Ni(NH3)2+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)22+ 2 2.16 4.89 (= log K1 + log K2) Ni(NH3)22+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)32+ 3 1.83 6.72 (= log K1 + log K2 + log K3) Ni(NH3)32+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)42+ 4 1.21 7.93 etc. Ni(NH3)42+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)52+ 5 1.03 8.96 Ni(NH3)52+ + NH3 Ni(NH3)62+ 6 0.09 9.05 Equlibrium constants can be used to calculate the concentrations of species present in solution. For example, what is the concentration of [Fe3+] in a solution containing 0.01 M [Fe(EDTA)]-, with log K1 for the Fe(III)/EDTA complex as 25.5 ? One has: 1025.5 = [Fe(EDTA)] / [Fe3+] [EDTA] Since the equilibrium in solution will be: [Fe(EDTA)] [Fe3+] + [EDTA], the concentration of [Fe3+] must equal [EDTA]. Thus, if the concentrations of the latter species are put equal to x, we have: 1025.5 = [Fe(EDTA)-x ]/ x2 Since [Fe(EDTA)] » x, this simplifies to [Fe(EDTA)]/ x2. Thus, if [Fe(EDTA)] = 0.01 M, then we have 1025.5 = [0.01]/ x2 We can therefore calculate that x2 = 0.01/1025.5, so that x = (10-27.5)½, So that [Fe3+] = 10-13.8 M. Formation constants for EDTA complexes are, like log K1 for hydroxide complexes, governed by metal ion size, charge and electronegativity. Thus, we have the effect of metal ions charge: Log K1(EDTA): Ca2+ 10.6 La3+ Th4+ 15.4 23.2 The effect of size is complicated by the fact that EDTA is hexadentate, and if a metal ion becomes too small, its complex will be destabilized. Thus, we have for the group 2 M2+ cations: Metal ion: Ionic radius(Å): Log K1(EDTA): Be2+ 0.27 9.7 Mg2+ 0.74 8.8 Ca2+ 1.00 10.6 Sr2+ 1.19 8.7 Ba2+ 1.36 7.9 What we see here is that Be2+ and Mg2+ are a little too small to accommodate EDTA adequately, but that after Ca2+, increasing size starts to affect the strength of the metalligand bonds adversely. The effect of electronegativity is one again that metal ions of higher electronegativity have higher log K1(EDTA) values than metal ions of similar size and charge, but low electronegativity: Metal ions: Ionic radius(Å): Electronegativity: Log K1(EDTA): Sr2+ 1.18 1.0 8.7 Pb2+ 1.19 1.9 18.0 Na+ 1.02 0.9 1.9 Ag+ 1.15 1.9 7.2 The Chelate Effect. Chelating ligands such as en form complexes of very much higher stability than two ammonia ligands. This can be seen for the series of polyamines below with Ni(II): Number of N-donors in complex: Log βn(NH3) for Ni(II): Polyamine: Log K1 for polyamine: H2N NH2 H2N en H2N 2 4.89 en 7.30 N H 3 6.72 dien 10.55 NH2 4 7.93 trien 14.0 H2N dien N H N H tetren N H N H 5 8.96 tetren 17.4 N H 6 9.05 penten 19.16 NH2 trien NH2 H2N N H2N N NH2 NH2 penten One sees that as the number of chelate rings in the polyamine increases, its stability relative to the ammonia complex increases steadily. This stabilization is known as the chelate effect. EDTA is a chelating ligand, which owes most of the stability of its complexes to the chelate effect. The chelate effect is an entropy effect, i.e. most of the observed stabilization derives from probability. In a solution of a metal complex such as [Ni(NH3)6]2+ at equilibrium, there is a rapid exchange of NH3 molecules and H2O molecules: fast 2+ [Ni(NH3)6] + H2O [Ni(NH3)5H2O]2+ + NH3 Thus, when an ammonia ligand falls off the Ni(II) complex, it drifts away in solution, and so there is a lower probability of it being re-attached. However, when one of the amine groups of, say, penten becomes detached, it cannot move away, and so is readily reattached. Chelating ligands are widely used for complexing metal ions, and EDTA and DTPA above are manufactured in large quantities for complexing metal ions in a wide range of applications ranging from food preservation to medical applications. Macrocycles and the Macrocyclic effect: In 1967, Charles Pedersen, working at DuPont, discovered the crown ethers. These are cyclic polyethers, as shown below for 18-crown-6, 15-crown-5, and 12-crown-4: O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O 18-crown-6 H3C 15-crown-5 O O O O 12-crown-4 O O CH3 pentaglyme Pedersen found that 18-crown-6 complexed K+ quite strongly, which was interesting, because alkali metal ions show little affinity for most ligands. Also of great interest was that it complexed K+ selectively compared to the other alkali metal ions. This can be illustrated with the log K1 values for alkali metal ions with 18-crown-6, plotted as a function of metal ion radius in Figure 10. It should be noted that, whereas 18-crown-6 forms quite stable complexes with K+ in water, the non-cyclic analog pentaglyme above does not. Figure 10. Variation of log K1 for alkali metal ions with 18-crown-6 as a function of ionic radius. What was particularly interesting was the structure of the K+ complex of 18-crown-6. It showed that the K+ fitted almost exactly into the cavity of the crown ether, as shown in Figure 11. Figure 11. Structures of alkali-metal ion complexes of 18-crown-6. At a) is the K+ complex (CSD code = AFITUE), showing how well the K+ fits into the cavity of the D3d conformer of the ligand. At b) is the Cs+ complex (CSD code = CSTHXD) shown sitting out of the plane of the crown ether because it is too big for the cavity. At c) is the D3d conformer of 18-crown-6 with an Li+ cation in the cavity (CSD code = BINKUE), showing that it is bound to only two O-donors from the crown ether, and has coordinated to two water molecules in the cavity to achieve a tetrahedral coordination geometry. The affinity that other metal ions have for crown ethers is controlled by their size, and generally, metal ions with an ionic radius greater than 1.0 Å form complexes of some stability with 18-crown-6. Thus, Pb2+ and Ba2+ have log K1 with 18-crown-6 of 4.3 and 3.8. The patterns of variation of log K1 with metal ion size with other crown ethers do not fit the idea of ‘size-match selectivity’ seen for 18-crown-6 in Figure 10, and in general it is found that K+ forms more stable complexes with most crown ethers than do the other alkali metal ions. This appears to arise from the fact that K+ is of an optimum size to complex with the chelate ring present in crown ethers, illustrated below, where it is seen that the lone pairs on the O-donors focus on a point some 2.8 Å away, which corresponds to the size of K+. H3C O O CH3 2.8 Å K+ Nitrogen-donor macrocycles: The N-donor macrocycles complex well with metal ions with more covalent metal to ligand bonding, such as Cu(II) and Co(III). As with the crown ethers, the N-donor macrocycle cyclam (= ‘cyclic amine’) below forms complexes that are thermodynamically more stable, i.e. have a larger log K1 value, than the non-cyclic analog 2,3,2-tet. H N N H H N Cu H N 28.0 H Cu N cyclam log K1 Cu(II): N H H N N H H H 2,3,2-tet 23.2 This extra stabilization is called the ‘macrocyclic effect’. In Figure 12 below are shown structures of the complexes of Cu(II) and Cd(II) with cyclam. Figure 12. Structure of a) the Cu(II) (CSD = HAFSUC) and b) the Cd(II) (CSD = UGOWOC) complexes of cyclam. It is seen that the small Cu(II) ion lies in the cavity of cyclam, but the large Cd(II) lies above the plane of the ligand. More Macrocycles - Cryptands: In 1974 Jean-Marie Lehn developed the cryptands. These are bicyclic macrocycles, as compared to the crown ethers and ligands such as cyclam, which are monocyclic. O O N O N O O N O O N O O cryptand-222 O O cryptand-221 The cryptands form complexes of much higher stability than crown ethers. This can be seen in the following series: O O O O O O O O O O NH NH2 O log K1(Pb(II)): 4.5 (Cu(II)): 7.9 HN H2N 6.7 6.2 O N N 12.4 6.7 What one notices here is that the large Pb(II) ion (ionic radius = 1.19 Å) is able to benefit from the high levels of preorganization of cryptand-222, whereas the small Cu(II) ion (ionic radius = 0.57 Å) is not able to bond ot all the donor atoms of the cryptand, and so does not show a complex of enhance stability. The structure of the Ba(II) complex of cryptand-222 is shown in Figure 13 below. Figure 13. Structure of the Ba(II) complex of cryptand-222 shown a) looking down the C3 axis, and b) viewed from the side.